From Imperialism and Conquest to Identification and Allegiance

Anglophone literature about the historical contact between Buddhism and the West focuses overwhelmingly on the Anglo-American experience, whether through 19th century encounters in Asia via the British Empire’s colonial administrators, scholars, and Christian missionaries or the American foray into Japan from the Tokugawa or Edo period (1603–1867) through to the occupation of Japan after World War II. For some Europeans and Americans, particularly those who had personal encounters with Asian Buddhists, imperialism turned into sympathetic identification with Buddhism and more broadly, Asia’s cultures and peoples.

This sense of identification (which often coexisted alongside the imperial imperative) led to some very important allegiances between Europeans and Western-educated but anti-imperialist local elites. The latter were galvanized not only by the new concept of nation-states and concomitant ideas like sovereignty and nationalism, but also by a renewed pride in their native spiritual traditions and a growing impatience with Christian-cum-colonial institutions. In America, the imperialism-to-identification phenomenon took place during the counterculture movement of the 1950s and ’60s, when a significant backlash occurred within a country that had displaced Britain as the foremost global power and was going through its own dark night of the soul with Communism and the Vietnam War.

Celtic Colonizers and Converts

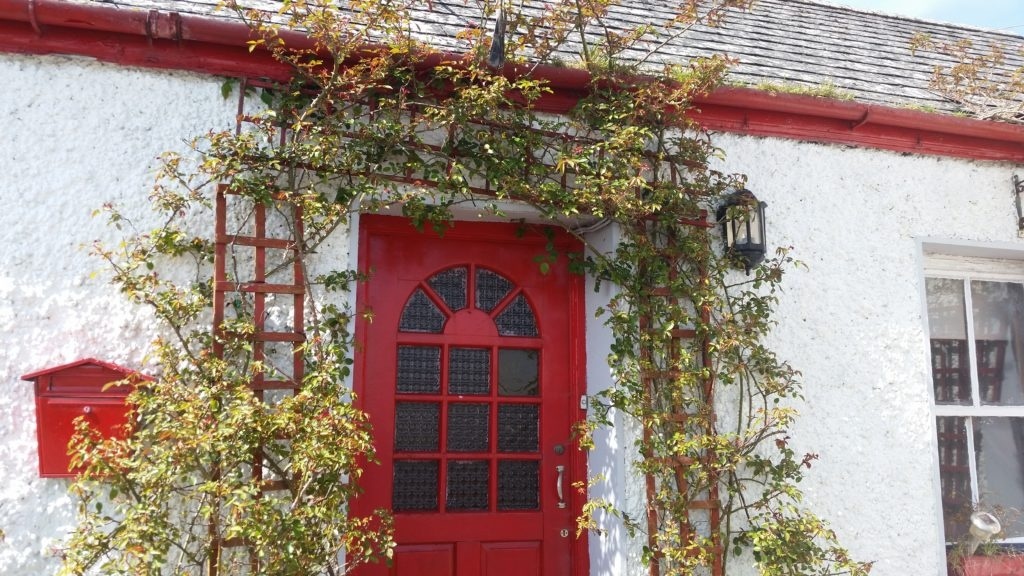

The case of specifically Celtic countries is somewhat more complicated. In Laurence Cox’s vividly written Buddhism and Ireland: From the Celts to the Counter-Culture and Beyond (2013), a dual identity of “colonizer and colonized” or “oppressor and oppressed” becomes the central focus of study. “Ireland’s encounter with Buddhism has been shaped by an international church, the British Empire and ‘blow-ins’ from more powerful western societies; circles of emigration and immigration have always characterised the encounter,” he writes (p. 52). If anything, the not-too-long-ago memories of the Irish Republic’s establishment in 1948–49 and the military violence and political upheavals of The Troubles (1968–98) brought the Irish experience of “colonizer and colonized” into even sharper focus. It is this narrative of the dual identity that forms the core of this absorbing and eloquent study about Irish attitudes to and interactions with Buddhism.

On one hand, “Irishmen not only helped to conquer Buddhist Asia; they also helped to rule it” (p. 118). Violence was rife (most famously in India, with Irishmen staffing senior positions in the East India Company as well as the British Raj). But the imperialism-to-identification experience was always present (p. 203), as well as a sense on the part of some who understood the oppressive nature of their work, such as Maurice Collis (1889–1973). His experience as an administrator in Burma “moved him from a naïve acceptance of colonialism towards recognising its exploitative nature, native resentment and British racism” (p. 121). Some Irish nationalists also identified the Asian Buddhist fight against Western imperialism with their own struggle (pp. 282–83). The typical Irish Buddhist from 1890 to 1960 was “a member of an Asian-led organisation opposing missionary Christianity” (p. 7). Ultimately: “Buddhism was tied to class desertion from the Anglo-Irish imperial service class, and later from the new Catholic nationalist service class; in one case alliance with Asian anti-colonial movements, in the other in alliance with counter-cultural migrants from other western societies” (p. 6).

Eurasian Past, Globalized Future

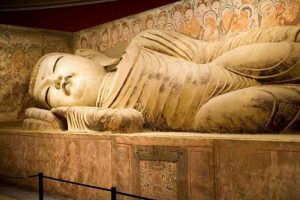

I have so far actually only addressed the second part of this book, which Cox titles “Caught between Empires: Irish Buddhists and Theosophists (1850–1960)” (although I think it is the most substantial). The first section is a masterful study of the interconnectedness of the cultures of Eurasia. It is titled “Thinking Buddhism in Ireland in World-systems Context (500–1850),” and Cox demonstrates that Buddhism was known in Ireland a full millennium before the first Irish converts to Buddhism appeared in the 19th century (pp. 48, 214).

“Buddhism, too, was not neatly bounded. First formed as traditional societies were reshaped by trans-Eurasian trade and royal states were built on the ruins of tribal republics, the later Buddhism of the long Asian Middle Ages saw established monastic sanghas tied to monarchial power. This now-‘traditional’ Buddhism was in turn replaced by forms of modernist Buddhism formed in anti-colonial contexts,” he writes. “The relationships between ‘Buddhism’ and ‘Ireland’ are structured by interactions within world-systems, and changes from one kind of world-system to another. This complexity is underlined by the time lags in the transmission of knowledge. Information from Alexander’s [the Great] fourth century BCE exploits became available in Ireland between the sixth and eleventh centuries CE, up to fifteen centuries later. . . . Trade routes East were in turn disrupted by the rise of Islam, so that until the thirteenth century the latest Irish knowledge of Buddhist Asia dated from the second and third centuries CE” (p. 52).

The last substantial chapter in Cox’s book is titled “Buddhism within Ireland: from Counter-culture to Respectability (1960–2013).” The rise of “contemporary” Irish Buddhism was actually preceded by a nadir of awareness about the religion in mid-20th century Ireland due to the collapse of the imperial service class, the terminal decline of the British Empire post-1940, and the little use that the rising Catholic service class had for Buddhism (p. 295). The revival of interest in Buddhism took place within what Cox calls a “hegemonic crisis,” specifically the challenges faced by many institutions, such as Catholicism, patriarchy, and capitalism, by non-Catholic movements, second-wave feminism, and the recessions of the 1970s and 1980s, respectively. He writes of many individuals who had diverse reasons for exploring Buddhism, and interviews members of the first Irish sangha (pp. 309–13). Finally, he offers an in-depth study of the present situation of Irish Buddhism and possible future directions, including its very intriguing fusion with “Celticity,” a compelling literary and political consciousness harking back to pre-Christian myths and archaeological sites, the Romantic Movement, and the cultural nationalism of William Butler Yeats (pp. 358–66).

Cox has written a careful and analytical account of the encounter between Buddhism and the Irish. It has set a wonderfully broad yet detailed and original context for the personal stories and journeys of converts, colonialists, and Irish nationalists that he peppers throughout. The book’s examination of Buddhism in the capitalist world-system that imperialism nourished and Irish resistance to this system is multifaceted and dispassionate, and does not shy away from nuance or complexity. This is high-quality Buddhist history—done in a sophisticated, sympathetic, and sociologically grounded way—that we urgently need to see more of today.

Buddhism and Ireland: From the Celts to the Counter-Culture and Beyond, by Laurence Cox, was published by Equinox Publishing Ltd., Sheffield, in 2013.