Part travelogue, part spiritual biography, and part artistic chronicle, Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo’s Threads of Awakening: An American Woman’s Journey into Tibet’s Sacred Textile Art (2022) is an eloquent work that is both adventure and homecoming; transformation and grounding. Leslie is a textile artist, teacher, and one of the few non-Tibetans to master the art of silk appliqué thangkas. In this book, which will be published on 23 August by She Writes Press, Leslie tells a tender human story of how she came to this artistic vocation, replete with emotional richness and raw honesty. A very useful and interesting appendix notes some of the foundational stitches and forms that Leslie has deployed for decades to make Tibetan-style appliqué.

There are two general contours to this book of six sections: the personal journey of spiritual and self-discovery and the learning and mastery of silk appliqué thangkas. Within each theme are many stories that place us alongside Leslie as she meets her first appliqué teachers, falls in love, or receives the Dalai Lama’s assignment to make non-Buddhist, indeed, Christian, thangkas. Highlights abound; anecdotes about her personal life set within broader cultural contexts that defined her as a Western convert to Buddhism. There are many sub-sections, but broadly there are seven parts, each denoting an aspect of weaving: “Fibers,” “Threads,” “Warp,” “Weft,” “Pieces,” “Reverence,” and “Buddhas,” with the sub-sections being called “Pieces.” The book can be likened to a tapestry of sorts about her life. But it is a story that cannot be told without looking at the individual components, much like her thangkas are never whole without attention to every single thread that, initially, seem to be unconnected to the other parts and sections.

The book begins with Leslie’s early background as an intellectually curious young student at the University of California, Santa Cruz, meeting Tibetans-in-exile, and her first encounter with the Dalai Lama on campus. The “official” beginning of this journey is a 1988 trip to Nepal and New Delhi, where she formally entered onto the Buddhist path:

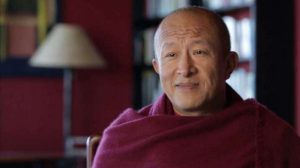

Just as a wedding ceremony doesn’t create a marriage, the refuge ceremony doesn’t create a Buddhist. But there is power in public declaration. . . . For me, taking refuge before Geshe Sonam Rinchen and Ruth was a way of declaring to my own mind-stream that the direction of my life’s journey, through whatever mundane events would follow, was toward inner freedom and understanding, using the Buddha’s teaching as a guide and compass.

(80–81)

In Piece 23, Leslie charts a brief history of Tibetan weaving, from the early days of silk imported from Tang China into the Tibetan Empire to how “a thriving production has reemerged among the exile community in India and Nepal, and a few large appliqué thangkas have been made within Tibet itself, including the giant Tsurphu thangka project in Eastern Tibet, managed by Terris and Leslie Nguyen Temple.” (115)

One of the distinctive advantages of this book is how much detail Leslie goes into with regard to the process of stitching, Tibetan style. This unique discipline, which she outlines, is worth quoting liberally. As she describes:

When you wrap that fibrous silk thread around a scaly hair from the tail of a horse, the thread’s fibers get caught in the hair’s scales. They cling, and the sheer strength of that clinging binds them. The thread remains securely wrapped around the hair. No adhesives are required. Now, I have to admit it took me weeks of practice to wrap thread around hair. It was a mess the first time I tried it.

(127)

Her discussion of highly technical processes, far from dry, is relatively unheard of in volumes discussing Buddhist art, since textiles are covered less often than paintings or sculpture. Furthermore, this is Tibetan textiles:

Tenzin Gyaltsen [Leslie’s teacher] showed me how to stabilize fabric by rubbing the wrong side of the fabric with raw meat and melting its grease into the fibers with a hot iron. The meat fat gave the flimsy fabric just enough stability to hold its form as we stitched curving cords across its linear weave. He introduced me to the Tibetan way of hand stitching, aiming the needle downward along a vertical path, rather than crosswise as Westerners usually do. I adapted quickly, almost as if I’d done it before. Each stitch made a loop that held my new horsehair cord to the surface of my meat-stabilized fabric. Loop after loop, stitch after stitch, I wedded cords to cloth along the lines of my drawing.

(128)

Aside from highly developed motor skills and a technical knowledge of the textiles, Leslie found her life in Asia inextricably linked with the revival of the textile discipline among Tibetans. This is especially important in Parts Four, Five, and Six, which are especially unique among publications about Tibetan art thanks to Leslie’s unique insight into the art of silk. In Piece 39, Leslie vividly describes a year of intense engagement—six days a week—with the motifs and designs of Tibetan art:

Birds’ eyes, snake eyes, deer eyes, eyes of snow lions and dragons. Garlands of severed heads hanging from wrathful shoulders. Humans and animals crushed under wrathful feet. So many faces. So many eyes. All helping someone to see more deeply into reality, to examine more closely the nature of their experience. Faces so small they sit comfortably in the palm of my hand. Day after day, eyes, eyes, and more eyes.

(178)

From her personal acquaintance with the basics, and eventual growth as a mentor in her own right, Leslie’s later development as a teacher mirrors the learning about life and stitching that she underwent decades ago. For example, she founded the Stitching Buddhas® Virtual Apprentice Program in 2008, an atelier that connects students from several countries and all over the US to learn, for six months, Tibetan appliqué (271). Not everyone will go to Nepal, India, and Tibet for a life-transforming journey. Few will have the commitment, time, or drive to truly master such a discipline as Leslie did. However, as her students progress in finesse, they can decide whether to enter into a membership program that will offer projects of increasing difficulty until, over some years, they are making thangkas just like their teacher.

Threads of Awakening is a book with multiple threads, so to speak, that each need to be tugged at lightly to see where they lead. There is one that will tell the story of a Western-born woman who found her spiritual path after a gradual journey that led to a fundamental realignment of her life priorities. There is another story about a professional woman who took the plunge into an unfamiliar world of sewing and threading, became intimately conversant in it, and reinvented herself with a new calling. They are all part of the same tapestry, although they have their own unique shades and vibrant colors. Leslie’s spiritual autobiography might technically be about herself, but her personable and insightful presentation stimulates introspection about our own journeys, whatever they may be.

Join Leslie in a Zoom talk on 28 June 18:00 PST, “Threads of Awakening: When Your Detour Becomes Your Life’s Path” when she will discuss her upcoming book Threads of Awakening: An American Woman’s Journey into Tibet’s Sacred Textile Art (2022).

See more

Threads of Awakening: Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo shares her experience as a California woman traveling to the seat of the Tibetan government-in-exile in India to manage an economic development fund, only to wind up sewing pictures of Buddha instead. Through her remarkable journey, she discovered that a path is made by walking it–and that some of the best paths are made by walking off course.