Despite the dominance of Vajrayana in the Western Buddhist imagination, the national epic of Tibet, The Epic of Gesar of Ling, is not well known. Sumer had Gilgamesh, and Homer’s Greeks had Achilles and the men of the Iliad. Gesar, meanwhile, is the ultimate Buddhist warrior-king with a Tibetan twist and a quintessentially Central Eurasian flavor. On a similarly comparable scale and significance, the exploits of Gesar might well be compared with the Western story cycles of the Matters of Rome, Britain, and France, with Gesar occupying a similar position to King Arthur and Charlemagne.

For centuries, Gesar’s tale was an oral work, passed down by bards until it splintered into multiple national versions, including the Persian, Indian, Mongolian, Ladakhi, Chinese, and Golok—between the Amdo and Kham—versions. There is no canonical version. The Mongolian was probably the earliest written recension, recorded in 1716. These variables have affected essential aspects of textual analysis, including a conclusion on exactly how long the story is, as well as the chronology or sequence of events. It is still upheld as perhaps the longest epic in the world, with the approximate length agreed to be 120 volumes and 20 million words.

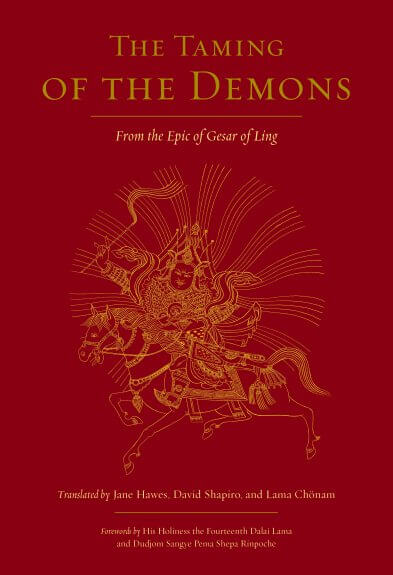

This monumental translation from Shambhala is of the fourth section of the epic, hence the title: The Taming of the Demons: From the Epic of Gesar of Ling. Three translators, Jane Hawes, David Shapiro, and Lama Chönam, worked on this volume, with the assistance of many veteran scholars such as George FitzHerbert, Samten Karmay, Geoffrey Samuel, and Timothy Thurston, and the support of Buddhist leaders such as Sangye Khandro.

The translation is based on a version of the epic that was compiled in the late 19th Century by Gyurme Thubten Jamyang Drakpa, Ju Mipham Rinpoche’s student. Lama Chöying Namgyal worked with Jane Hawes to produce the first translation, which was published in 2013. The present publication was translated from the text The Battle of Düd and Ling, and compiled by Tendzin Phuntsok from narratives compiled by a committee of qualified scholars. These administrators and scholars based the collection from recordings of the song “The Taming of the Northern King Lutsen” sung by the bard Drakpa, and the published story The Taming of the Seven Wayward Siblings. This, in turn, was sourced from two previous texts, The Taming of the Māras and A Chapter on the Māras. (xvi)

One of the great joys of reading this translation—which is conveyed in crisp, contemporary English while retaining fidelity to Gyurme Thubten Jamyang Drakpa’s version—is uncovering just how many layers of Buddhist influences, Central Eurasian influences, and Indo-European folk memory and cultural identity can be found. As the preface states, said influences incorporated into the various versions “span from Rome to Burma and from Mongolia to Bhutan.” (xv) Furthermore, local Tibetan myth and archetypes, specifically Bön magic and deities, permeate the text. It is fitting that since the 1960s, Gesarology has been a legitimate discipline, no matter how obscure or little-known.

The story so far

The Taming of the Demons is generally agreed to follow Gesar’s birth and coronation, which comprise the first three chapters of the epic. Gesar’s story is one of magic, war, and divine destiny. His character possesses archetypes of the Indo-European warrior hero in the following ways:

He is born into a troubled time of political intrigue and change. Before Gesar is born, the Tibetan plateau and greater Eurasian steppe is in turmoil; Buddhism has been newly established in Tibet, but war, feuding aristocrats, and plague and disease ravage the newly converted land. His existence is a result of divine destiny, prophecy, or ordinance. The bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara takes pity on the Tibetan people and discusses with Amitabha Buddha how a superhuman being might be able to appear in the world and unify the Tibetans and protect them from the many enemies at their borders.

He is born with extraordinary characteristics and divine qualities or blessings. Gesar already has a name in the celestial realm, Döndrub, and negotiates a good rebirth to the appropriate parents. He is born in the land of “Ling” as Joru to his mother, Gokmo, who as a naga princess also has semi-divine origins (another common characteristic of mothers of protagonists in other heroic epics). He is also born into the world as a three-year-old, with a comprehensive knowledge of the Buddhist scriptures and overwhelming charisma and charm. The hero has a rebellious childhood with a powerful mystical-religious advisor and an older figure plotting his downfall. In this case, the renowned Padmasambhava is the narrative tool that encourages Joru’s naughty, unruly behavior, along with a sorceress called Aunt Manéné.

A treachery is performed against him or his family, usually by an older relative plotting his downfall, and he is exiled. His uncle, Trothung, banishes him and Gokmo to the land of Ma. However, he is then re-welcomed into his immediate community or society, whether through deception or redemption. In Joru’s cases, it seems to have been deception. With divine assistance, Joru is able to cause a harsh and powerful snowstorm that forces the people of Ling to appeal to his mercy. He offers territory in Ma to the people of Ling, and once the snowstorm passes, they return to Ling.

The protagonist hatches a plot that will trick the object of his vengeance. Aunt Manéné and Joru propose the idea of a horse race to Trothung, and Trothung is forced to invite Joru to participate. The prizes are nothing less than sovereignty over Ling, the wealth of the richest man in the land, Kyalo Tönpa, and the hand of his daughter, Drukmo. He realizes his heroic self after a great trial, acquiring a new rank or name. The race begins and the somewhat lax Joru needs a talking to by Manéné before he rallies and wins. After his victory, Padmasambhava triumphantly confers on Joru his destined name, Gesar Norbu Dradül.

The hero’s rampaging revelry

The Taming of Demons chronicles over 16 chapters how Gesar takes on the world. It is beyond the scope of this review to offer a detailed summary, given the intricate plot details and narrative twists and turns. As with all chapters in the epic, the story and ballads are vivid and epic, describing grotesque transformations, blood sacrifices, summoning gods and demons, and infiltrations and betrayals. As the translators’ preface goes:

. . . this is much more a martial story of battles won and strategies applied. It is a story that may appear gruesome at times, but as in all Gesar stories, the vanquishing and destruction of enemies is done with the full heart of compassion and with a view toward the eventual liberation of those who are vanquished. This story . . . chronologically follows Gesar’s ascent to the throne and is the first in which he acts as a general and leader for the land of Ling.

(xi)

Describing the glory of a fully-armed Gesar, riding out to lead the troops of Ling against his demonic enemy, invokes a true warrior archetype of the Central Eurasian martial culture, complete with a magical steed and a “comitatus”—an inner circle of loyal men that will fight alongside him to the death, be it a royal guard, the Knights of the Roundtable, elite bodyguards or lieutenants, and so on. Their enemies are so-called mara-gods,

The Ling military standard bearer, the one who was the core of its one hundred thousand troops, the hammer of the enemy, Denma, was a man so blue—armored with nine types of blue weapons and mounted on a blue steed—that it appeared as though a turquoise dragon had risen from a crystal blue lake. Then, descending like a thunderbolt, came the unsurpassed warrior, Gyatsha Zhalu Karpo, the butcher of the hateful enemy. White-robed, riding a white horse, and armed with white weapons, he looked like Brahmā going to war. With his nine courageous dralha guardians concealed in the crook of his arm,15 he led the army column. In its center was Gesar. His face caught one’s attention as would the luminous full moon. Luxuriant eyebrows sparkled above his piercing eyes, and his teeth shone like a conch garland between his deep vermillion lips. His wisdom eye was vibrant and his hair, dark and shimmering. Dralha and werma gathered like clouds. Equipped with the armor and weapons of the dralha, as though he were Indra preparing for battle, Gesar was so resplendent that it was difficult to gaze upon him. Manifesting the power to magnetize and overpower the three worlds through his splendor, he rode upon Kyang Gö, the formidable mount tacked with the accoutrements of a great steed.

(71)

The descriptions of the battles are violent, thrilling, and filled with magic spells and daring maneuvers. Key to the story is the usurped uncle Trothung, who is set up as a Judas-like figure who, for all his cowardice and resentment, was able to prompt Gesar to manifest his wrathful side, his Dharma warrior self, and hence claim his destiny. The chapter therefore articulates how a hero cannot realize their potential without an enemy. But the epic does not position uncle against nephew in an absolute sense, as in King Lear. Surprisingly early on, Gesar resolves to spare the cowardly and vengeful Trothung, not only because of their familial connection but also because of Trothung’s own status as an emanation Red Hayagrīva. As Manéné sings to Gesar in verse, preparing him for the coming conflict, we see that this classic heroic motif of enmity between protagonist and familial elder is recast as a bodhisattva’s divine plan:

through the aspiration prayers of the divine ones above,

(42)

at this moment, is helping you, even as he seems to be causing harm.

If he did not spoil your heartfelt feelings of love for him,

you would not know how to act.

Therefore, you are indebted to Trothung.

Trothung himself sings,

If I had not been chosen as the one to deceive him—

(89–90)

Gesar, an awakened one,

would never have displayed his wrathful side.

If I had not concentrated all my energy,

Gesar would never have stood a chance.

Without all my machinations,

Gesar would never be renowned in these three regions of Tibet.

Oops, I was not supposed to say that—just joking!

Trothung and Gesar reconcile (115–18) and Gesar successfully exorcises one of his enemies, a demoness called Bloody Tress. Gesar is an extremely powerful sorcerer himself, and is able to take on many forms. As an exorcist, he can defeat his foes while not destroying them and freeing them to reform themselves. Bloody Tress is one such example:

“Through his wrathful activity, the demoness was liberated, and her body offered to all the deities. Her consciousness forcibly tried to eject, but, because of her deep-seated impiety, she took rebirth as the daughter of a cannibal in the village of Darika. Gradually, through the power of aspiration prayers, she became a suitable vessel able to be tamed by the great guru Vikramaśīla.”

(125)

The epic therefore retains ancient textual layers of the Buddhist missionary tendency to not annihilate the local gods of a region into which it diffuses, but to render them guardians of the Dharma.

Thus is the tone set for the rest of the story, with almost every page of this translation erupting with lines that show off not just the exuberant piety of the pious, but the consummate skill of the bards in retelling what truly gets the blood going: Gesar’s heroism and his manly control over all things, even his demonic enemies and the foes of Ling, his beloved realm. The Taming of the Demons is therefore all about Gesar subduing powerful demons after epic confrontations. Kyang Gö, the faithful steed which accompanies Gesar, is himself a unique character that accompanies him on later adventures through the chapter. He is not simply to Gesar what Pegasus was to Bellerophon, or Bucephalus to Alexander. He regularly sings, discusses, and parlays with Gesar, a veritable equal to his rider. After all, he is none other than an emanation of Amitabha Buddha, and their shared fate is one that is both a burden and a commission that will liberate the entire cosmos. As he sings to Gesar, in a ballad that is full of poignancy and what one might call Buddhist pathos—mindfulness of the burden of the bodhisattva’s destiny, in particular that of the wrathful bodhisattva:

We are the ones entrusted to send the māras to the hell realms

and to lead the six classes of sentient beings to liberation. . . .if anyone is to be liberated,

(331)

we are the ones to guide them to the pure realm;

if anyone is to be sent downward,

we are the ones to lead those sinners to the hell realms.

Between heaven and earth,

we are the ones to benefit beings.

That is our heavy responsibility.

In this great existence,

there are countless sentient beings of the six classes,

and therefore no end of enlightened activity required for their benefit.

In this samsaric world,

although you and I will endure great hardship,

there is no reason for regret.

That is the nature of what we have been asked to do.

The Taming of the Demons ends with Gesar getting drunk and unable to take up his duties, remaining at the “mara castle” for many years to come. This episode, along with his previous battles and exploits, hints at the archaic leitmotifs of Gesar’s hero persona, which was overlaid with Buddhist influences only after a complex mix of folkloric patterns found in Greco-Roman, Persian, Turkic, Indian, and Inner Asian (Mongolia, Tibet, and Bhutan) were worked into the various versions. The poem itself mentions various regions such as Persia and Mongolia, with foreign realms described poetically and graphically as dangerous lands with deadly landscapes. Persia, for example, has plains that are perpetually on fire. Gesar is therefore a unique figure in the vast corpus of Tibetan Buddhist literature, a “Mr. Worldwide” character who gets drunk, fights, courts beautiful women, and crushes demonic forces: all with the blessing and at the direction of Avalokiteshvara himself. At multiple points throughout the text, Gesar and other characters are at pains to remind the reader that all is happening as planned; that even the brash and invincible Gesar is but a tool being wielded by Avalokiteshvara. This notion of fate is yet another similarity with other great epics, albeit for a happy teleology relative to those that end up with tragic endings for those puppeteered by the gods.

Any epic requires patience and time to ease into, but thanks to the eminently intense and modern English of the present translation, the experience is immersive. It is a joy to read for multiple constituents. It will be new for those who have not had the pleasure of encountering a true Buddhist epic to match those belonging to the lifeworld of, say, the Greco-Roman world or that of medieval Christendom. But this text will challenge Buddhists as well, with its vision of a martial culture in which war is a fact of life and donning “the armor of compassion and loving-kindness,” and drawing the “curved blade of the sword of prajñā” (128) can be uttered with a straight face. Gesar is the Mahayana ideal man incarnate on Earth: the peerless ksatriya of ancient Eurasian, Indo-Iranian life-world, his sword reflecting the war cries of multiple cultures across the steppes and mountains. He loves battle but he loves his enemies even more. The Buddha’s true and eternal Dharma is why he rides to meet them on fields soaked with blood. Blood that, true to Vajrayana Buddhism, transforms a place of slaughter, spells, and swords into a Pure Land.

See more

Hawes, Jane, David Shapiro, and Lama Chönam. (Trans.) 2021. The Taming of the Demons: From the Epic of Gesar of Ling. Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications.