In 1980, not long after death of Mao Zedong in 1976, Xi Jinping—then just a young Party secretary—visited the Chan temple of Linji in the town of Zhengding, in Hebei. The next few years would see Xi confer numerous privileges on the Buddhist institution that his father, CCP grandee Xi Zhongxun, could never have foreseen. In a way, Xi’s relationship with Linji Temple and its abbot, Ven. Youming, would become symbolic of a gradual rethink of religion’s role in post-1980s China. Today, the spiritual stakes in the country have never been higher, with a resurgence in popular interest and increased involvement by the government, along with religions’ massive potential to transform Chinese society for good or ill, depending on one’s perspective.

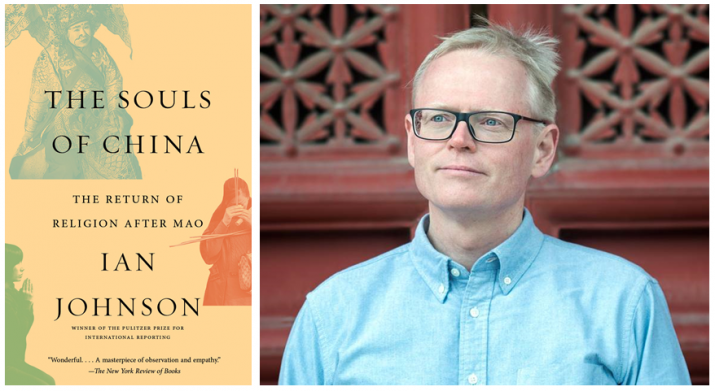

Few human endeavors are as deep and primordial as religion and few countries are as vast and multifaceted as China. Religion in China is, not surprisingly, a tricky beast to have even a basic understanding of without resorting to Western categories or long-established tropes. Writer Ian Johnson (who last year penned an excellent article about China’s renewed engagement with religion in the American magazine Foreign Affairs) foreshadows this perennial issue with some reflections in the second sub-chapter of his newest book, titled “Ritual: The Lost Middle.” He rightly emphasizes that loaded Western vocabulary (including the very word “religion”) is not helpful for surveying the explosion of faith in China due to complex historical and present-day factors. “Instead, it is much more useful to ask people how they act, or whether they believe in specific ideas.” For example, Johnson notes that people respond much more positively when one speaks of xinyang (信仰)—faith, than zongjiao (宗教)—religion.

It is fitting that Johnson’s book title has a sense of grandness that matches the complexity of the subject matter: The Souls of China. Johnson has crafted a story specifically about the Han people—“They dominate China’s economic, political, and spiritual life; their journey, for better or worse, is China’s journey.” The subtitle, The Return of Religion After Mao, indicates the journalistic ambition of the book, which combines grand narratives about the Chinese government’s engagement with the country’s many religious groups with intimate portraits of everyday Chinese. Johnson has spoken with a cross-section of people across China, from rural residents to urban municipal officials. The result is a magnificent yet relatable tale of China that encompasses many smaller stories—all of them fascinating and worth thorough reflection.

The centrality of these smaller stories to the bigger, national one is indicated at the beginning of the book, with a list of the cast of characters. Johnson portrays Buddhism as one influential player (but very clearly not the only thread) among the larger tapestry of religions competing for the people’s spiritual loyalty. There are “the Beijing pilgrims” of Miaofengshan and “the Shanxi Daoists.” “The Chengdu Christians” and “the masters.” Each character deserves their own analysis and unpacking, something I can’t do justice to here, but suffice to say that Johnson deserves credit for following them and integrating their everyday lives into the wider macrocosm of Chinese faith.

We know from the 2007 China Spiritual Life Study by Perdue University that 185 million people (roughly 13 per cent of the population) consider themselves Buddhists, with 17.3 million having formal ties to a temple as lay Buddhists (ju shi). A government survey in 2014 noted that there were 33,000 Buddhist temples in China and 500,000 monks and nuns residing in them. The Buddhists Johnson has written about include Nan Huai-chin (a meditation guru and interpreter of Chinese classics who lives in a hermitage on Lake Tai) and Ni Jincheng (a Beijing-based reclusive Buddhist). They are important sources for Johnson, but by no means the only ones. Indeed, The Souls of China places the Buddhist story within the broader Chinese narrative, reminding those of us with Buddhist sympathies and affiliations that there are many different factions and forces at work in the restoration of religion to public life.

The government’s interest in religion—even if only in its state-sanctioned forms—is both self-interested and sincere. It is an implicit concession that pure Marxism, and even socialism with Chinese characteristics, is not enough for Chinese citizens and indeed not even for a large portion of Party cadres and leaders. Religious need and revelation come from somewhere deep in the human condition and can be amplified by societal and cultural trends. Document 19, or “The Basic Viewpoint and Policy on the Religious Question During Our Country’s Socialist Period,” lays out the legal and moral basis for recognizing the need for the flourishing of the religions under the guidance of the Chinese Communist Party.

Johnson’s book has done an estimable job of tying this primal need with the complex facets of Chinese society, from family life to the economic boom to government intervention. Since I’ve focused only on the Buddhist aspects, I haven’t come close to addressing the other complex and fascinating characters. Despite the cliché, I’m happy to suggest that Johnson’s book is an up-to-date tour de force that deserves to be counted among the most comprehensive and balanced English-language journalistic volumes on religion in the Middle Kingdom.

See more

China’s Great Awakening: How the People’s Republic Got Religion (Foreign Affairs)