The study of maritime Buddhism along the littoral hubs of Asia is enjoying a surge in scholarship. There is one critical component that distinguishes the littoral conception of Buddhist diffusion from the more familiar, overland paradigm of the Silk Road (which, over the decades, has enjoyed more public awareness and popular cultural, media, and literary interest). In the Chinese Buddhist experience, the importance of sea routes endured long past the lifespan of the overland Silk Road, which was more or less closed by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). In contrast, the maritime Silk Routes were critical in shaping the religious, social, and cultural landscapes of today’s Southeast Asia. Events there reverberated back to China, in turn influencing Buddhist developments on the Chinese mainland.

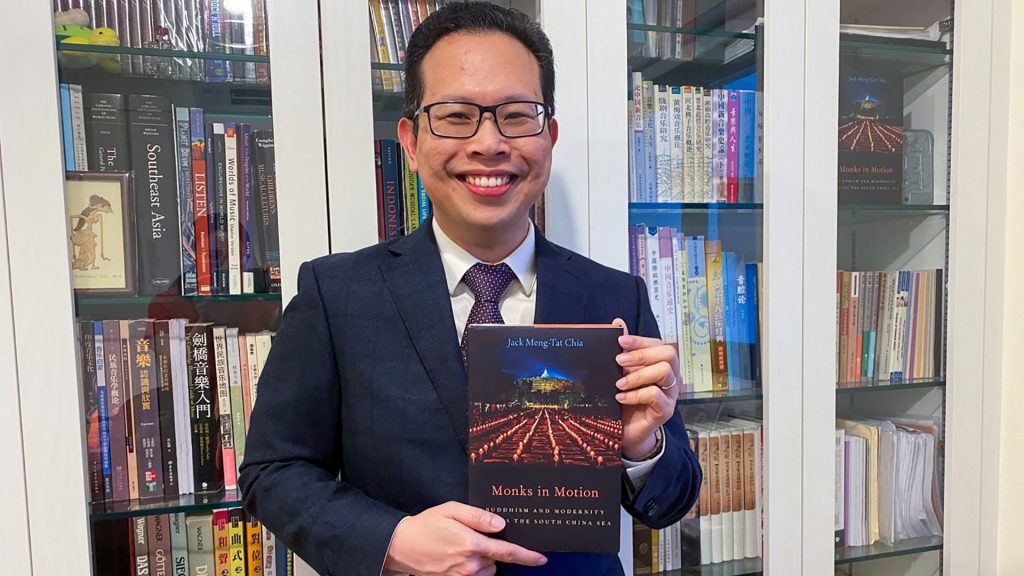

Prof. Jack Chia’s first book, Monks in Motion: Buddhism and Modernity Across the South China Sea (2020), is among the most recent monographs to contribute to this rebalancing of academic coverage. I had the pleasure of meeting Prof. Chia in Vancouver in 2016, before he took up his current post as assistant professor of History and Religious Studies at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He earned his BA and MA from NUS, and then a second MA from Harvard. He obtained his PhD from Cornell, his doctoral dissertation winning the Lauriston Sharp Prize. His research focuses on “Chinese popular religion, Buddhism in maritime Southeast Asia, transnational Buddhism, and Sino-Southeast Asian interactions.” (National University of Singapore)

Prof. Chia’s book demonstrates that the circulation of Buddhism along the nodes of the South China Sea shaped different modes of “Buddhist modernity” in post-colonial Southeast Asia. This lends the story of maritime Buddhism a contemporary relevance that is simply not available to the overland Silk Road circuit. This is one of the only Buddhism-themed books to have won the EuroSEAS Humanities Book Prize 2021, an award given to the best academic study on Southeast Asia published in the humanities. Furthermore, beyond this innovative book, Prof. Chia is also working on two other monographs: Beyond the Borobudur: Buddhism in Postcolonial Indonesia and Diplomatic Dharma: Buddhist Diplomacy in Modern Asia.

Monks in Motion is divided into four main chapters: “Migrants, Monks, and Monasteries, “Chuk Mor: Scripting Malaysia’s Chinese Buddhism,” “Yen Pei: Humanistic Buddhism in the Chinese Diaspora,” and “Ashin Jinarakkhita: Neither Mahāyāna nor Theravāda.” The South China Sea is the shared littoral core of many different countries that, taken together, shaped what could be called Southeast Asian Buddhist modernity. The countries Prof. Chia focuses on are the modern nations of Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia, with frequent reference to the Chinese mainland. He offers a rethinking of what “Southeast Asian Buddhism” means from the following angles:

1. Chinese migration and the spread of Chinese Buddhism to Southeast Asia,

(6–7)

2. the participation of Chinese monks in the transnational circulations of people, information, and resources in the South China Sea,

3. the role of diasporic monks in the advancement of Buddhist modernism in maritime Southeast Asia, and

4. the rise of maritime Southeast Asia as a center for Chinese Buddhism in the Chinese periphery following the establishment of the communist People’s Republic of China on the mainland.

As this list foreshadows, Prof. Chia challenges a dominant mode of thinking that privileged Theravada Buddhism, maritime Islam, and Catholicism in the historiography of Southeast Asia. Rather, he attempts to shed light on how Chinese migration and subsequent Buddhist communities in maritime Southeast Asia developed their own senses of religious modernity. (9) In other words, he hopes to open up a new front in the study of this region, rather than only from the dominant China-centric or Theravada/Islamic/Christian-centric viewpoints:

Just as the current literature on modern Chinese Buddhism says little about Chinese Buddhism beyond China, most studies on Buddhism in Southeast Asian history and society are shaped by a teleology leading to the formation of Buddhist majority nation-states. The purpose of such a narrative is typically to present the intertwining relations between Theravāda Buddhism, nationalism, and nation-building in mainland Southeast Asia. Consequently, the dichotomous framing of mainland Theravāda Buddhism/ maritime Islam and Catholicism has become a common trope to conceptualize the religious diversity of Southeast Asia as a region.

(156)

Prof. Chia terms this proposed new front “South China Sea Buddhism,” given the connection of Buddhist communities between Buddhist China and Southeast Asia. Early on, Prof. Chia addresses some relatively well-known information about the transmission of Chinese spiritual beliefs, in particular folklore and syncretic beliefs involving Daoism. (19–24) But the journey of institutional Buddhism is, in my view, a much lesser-known aspect of Southeast Asian religious development in the 20th Century. (24–30)

The three monks who are Prof. Chia’s main protagonists (Chuk Mor, Yen Pei, and Jinarakkhita) were extremely important figures. Chuk Mor, the inaugural president of the Malaysian Buddhist Association (the earliest Buddhist body in Malaysia, founded in 1959), propounded a form of Buddhist modernism that redefined the idea of being Buddhist, which was based on Taixu’s ideas of “Human Life Buddhism.” (157) Yen Pei, who came to Singapore from Taiwan (once from 1964–79 and then from 1980 to his death in 1996), based his modern Buddhist vision for Singapore on “evangelism and education.” This meant the establishment of schools as well as social work, such as alleviating poverty and helping the aged, enabling organ donations and transplants, and drug prevention and rehabilitation programs. (158) And finally, Jinarakkhita was essentially the father of “modern Indonesian Buddhism,” which he called the Buddhayāna movement, having developed it in accordance with the perceived needs of the modern Indonesian state. This new Buddhist movement was compatible with the national discourse of the Pancasila, or “Unity in Diversity.” (159) He also took the big doctrinal risk in propounding the Sang Hyang Adi-Buddha and the notion of “theistic Buddhism” to ensure Buddhist survival under the Suharto regime, much to the disquiet of Theravada Buddhists.

Prof. Chia charts how Chinese migrants, over the course of many historical incidents and trends, shaped expressions of Chinese Buddhist modernity: this sense of modernity was characterized by, as Prof. Chia notes, “scriptural authority and historical legitimacy, but also the contingency of action and monastic intentions. Setting itself in opposition to pre-institutional Chinese Buddhism, Buddhist modernism in maritime Southeast Asia incorporated notions of orthodoxy from ideas of Buddhist reform movements in China and Taiwan and from the concerns of modern nation-states.” (159)

At the end of his book, Prof. Chia asks: “To what extent, if at all, did the presence of Chinese modernist monks in mainland Southeast Asia help to influence and inspire mainland Southeast Asia’s modernist Buddhist movements during the second half of the 20th century? What kind of missionary impulses and modernizing sensibilities did these monks share?” (160) These questions are not easy to answer. Therefore, the next step would perhaps be an ambitious examination of the multifaceted networks and interactions among monastics in Greater China and Southeast Asia. This would demand scholarship that can read sources in Burmese, Khmer, Lao, Thai, and Vietnamese. The dynamics, whether collaborative or adversarial, between the pre-institutional Buddhist community and the modernist monastic community, are worth further exploration. Finally, Prof. Chia proposes opening up a conversation about how Chinese monks participated in anti-Communist activities at the height of the Cold War in Asia, and deployed South China Sea Buddhist networks to connect with activists, state actors, and ideologically aligned Buddhists.

This book is ambitious in scope, covering diverse and complicated Asian societies that went on divergent paths of Buddhist modernity. Monks in Motion succeeds admirably in tying together lesser-known spheres of Buddhist influence to form a persuasive narrative about the development and contribution of Chinese Buddhism to the spiritual milieu of Southeast Asia. Thanks to studies like this one, an increasingly comprehensive history of Southeast Asian Buddhism has never been more accessible. Gone are the days when schools of Buddhism in Southeast Asia were studied in thematic or denominational silos, or when entire periods such as the post-colonial era would be skipped over due to a dearth of scholarship. While there is much more work to be done, as Prof. Chia notes, the ball has begun to roll, and scholars like him will be sure to maintain the momentum.

Reference

Chia, Jack Meng-Tat. 2020. Monks in Motion: Buddhism and Modernity Across the South China Sea. New York: Oxford University Press.

See more

NUS History Asst Prof Jack Chia Wins EuroSEAS Humanities Book Prize 2021 (National University of Singapore)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

The Buddha at Sea: Atlas of Maritime Buddhism and New Experiences in Museology

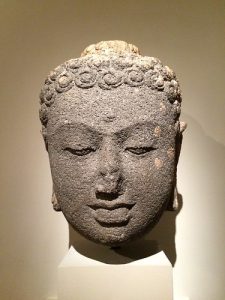

Mahabhikksu Ashin Jinarakkhita: The Father of Modern Indonesian Buddhism

Rediscovering an Ancient Heritage in Indonesia