The koan’s primary virtue is in disrupting our normal, habitual way of dividing the world. Koans are like banana peels all over the floor—they maximize the possibility of slipping through dualism and seeing true nature. (20–21)

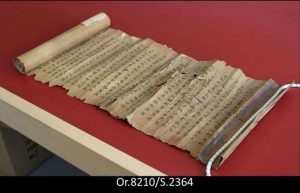

Koans are an intricate aspect of Zen Buddhist practice and it was historically common for notable Zen masters to create koan collections, which they referred to when teaching. Some of the better-known collections include The Blue Cliff Record and Book of Serenity. A less well-known collection—at least in the West—is The Record of Empty Hall, which was written by the influential figure Xutang Zhiyu (1185–1269). A contemporary of Dogen (1200–53), Xutang was a big deal in China during his lifetime. The role he played during the period of the transmission of Zen to Japan was significant, and his legacy lives on today in the Japanese Rinzai school. Despite this, his teachings and their impact are often overlooked.

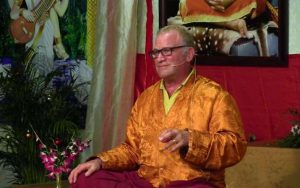

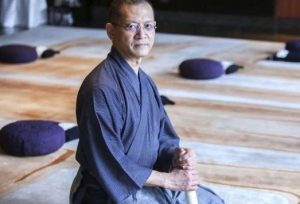

Drawing attention to Xutang’s teachings is American Zen teacher Dosho Port, who recently published a translation of Xutang’s koan collection titled: The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans (Shambhala 2021). Port provides an excellent overview of Xutang and his significance, both during his own era and to this day. Port also describes his own relationship with Zen Buddhism and highlights “the dumb luck” with which he bumped into one of the first Soto Zen teachers in America—Dainin Katagiri Roshi—in Minneapolis in 1977. (1) Port received Dharma transmission from Katagiri Roshi in 1989 and received inka shomei from Ford Roshi in 2015, in the Harada-Yasutani lineage.

Having familiarized himself early on with Soto koan study, Port describes his enchantment at coming across Xutang and his work:

Although I’d already been practicing and studying Zen for decades, I didn’t know anything about Xutang, so I began digging. I soon felt like a little kid discovering a cache of golden pennies right in my own sandbox! (2)

According to Port, Xutang was “strongly ecumenical” (228) because he drew from all five houses of classical Zen. Having ordained as a monk at the age of 16, Xutang subsequently served as the abbot of 10 monasteries and had a strong following of practitioners, including two emperors: Lizong and Duzong. Port writes:

And, yet, despite [Xutang’s] importance to the lineage of practice, and to our practice today, his contributions largely lay hidden, although not rotting. More like a helping hand extending from the grave. (11–12)

For all his praise of Xutang’s contributions, Port emphasizes the fact that his collection of koans “is not a record of diversity and inclusion.” (16) A product of the times, the collection features cases that largely center around male monastic communities. As such, the stories can come off as a never-ending intellectual game of one-upmanship engaged in by a handful of privileged men. That said, if you have this impression, I would encourage you to continue reading—even if the people engaged in the debates may not always seem relatable, the koans, when kept close and pondered over, are real gems.

Additionally, Port does an excellent job of shining a much-needed light on Xutang’s work and, in his playful way, making it more relatable to the contemporary reader. The following two passages provide wonderful examples of how he interweaves his personal life into the commentary, making it familiar and inviting:

In any case, I often think of my native country, northern Minnesota—family, the short-treed forests, swamps, and, of course, Lake Superior. What familiar place can you not forget? (128)

So much noise. So much commotion. Now the old black dog just sleeps on the rug. My wife prepares early morning tea for us in the next room, and soon we will be going to the zendo to sit zazen. Lifting up the corner of this robe, the cotton, the connections within the robe and within the fibers, the farmers, truck drivers, and merchants, the culture of making the robe just so, and, of course, the earth, sun, moon, and stars, the gentle talk we had under the covers, they are all lifted up. (191–92)

At times I felt as though I was right there with Port, practicing in his living room, surrounded by the same sights, sounds, and smells. As someone who is relatively new to the world of koans, I felt reassured by his writing style. His humility and his assertion that “there is a lot of stupid to go around in Zen, and we’re all in such good company” helped me to accept that I would be lucky just to scratch the surface of these koans in my first read. (3) After all, the koans are not meant to be resolved—rather, they encourage the practitioner to make use of the inquiring mind, so that they may catch a glimpse at the true nature of things.

References

Port, Dosho. 2021. The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans. Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications.

See more

On Receiving Inka Shomei from James Myoun Ford Roshi (Patheos)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Book Review: Silent Illumination: A Chan Buddhist Path to Natural Awakening

Book Review: Norman Fischer’s When You Greet Me I Bow

United by Our Common Vows: Tenku Ruff on Soto Zen in North America

The Most Intimate

The Way of Ordinary Life: An Interview with Karen Maezen Miller

Visions from the Zen Mind: Zen Paintings and Calligraphy at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Gift of Zazen: Angie Boissevain

Continuing the Legacy of Chan Master Sheng Yen