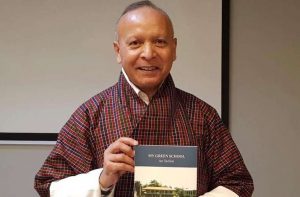

Shambhala Publications published A Meditator’s Guide To Buddhism: The Path of Awareness, Compassion, and Wisdom by Cortland Dahl in September.

After a warm and personal foreword by Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, the author’s teacher, we are introduced to a simple truth-story about our own inner treasure. Cortland, our author, delivers this exposition in a language and style that our contemporary mind can settle into and feel safe with, trusting that the rest of the journey will feel like a friend holding our hand rather than a professor instructing us to open page one of an encyclopedic tome.

In his introduction, Cortland reminds us that Buddhism differs from other religions, noting that many suggest that it not be considered a religion at all, as it is more of a guide to evolving one’s awareness and enlightenment than a relationship with a godhead. In doing so, Cortland opens his book to readers who may be more interested in learning about a profound philosophy that can be applied in practical ways to engender a healthy state of being, delivered through the lens of the Tibetan Buddhist path.

Indeed, this book is almost a how-to manual, although not quite, but far from an academic treatise as Cortland introduces newcomers to the core tenets of Buddhism. Like laying a secure track for the train of practice, he leads us on the journey of the three Buddhist vehicles, known as yanas: Hinayana, Mahayana, and Vajrayana; as well as the Four Noble Truths, and how all of this is useful and applicable in our modern world.

Even the retelling of the story of Shakyamuni Buddha feels appropriately fresh and relatable.

Mingyur Rinpoche’s forward isn’t the only personal touch, as Cortland skillfully intertwines Buddhist history, teachings, lessons, and his own experiences in a warm, flowing, and friendly way. Those with years of Buddhist training may also find concepts rephrased and delivered in such a way as to spark novel perspectives and thoughts.

As someone who deeply values the introspective questioning “technique,” both personally and professionally, I also appreciate Cortland’s use of this as part of the conversation. Introspective questions are dropped in, as are meditational exercises, so that much like grabbing a cup of water during a marathon, we are able to refresh ourselves while we stay in motion.

Without feeling like Cortland is handing us a gold star for simply showing up, he also reminds us not to beat ourselves up for being human. And for that alone—although there is so much more—this book’s place in the “how-to” library is well and truly deserved.

As a sign of the changing times, I have noticed a shift in what Dharma teachers emphasize regarding the pressing issues of the day. And rightly so. This is one of the significant attributes of Tibetan Buddhism that set it apart from religious dogma. In the hands of the wise, Buddhism is free of rigid zealotry and helps us to explore how the teachings can be useful in the context of cultural change. This includes inquisitive explorations of what science brings to the conversation, as well as our evolving understanding of meditation and neurology—something in which Mingyur Rinpoche himself is known to have participated. Other cultural issues include human rights, environmental conservation, and compassionate diets.

I was reminded of this as I read: Cortland reflects on the importance of compassion and of being conscious of the effects that our choices and actions have on our interconnected world. As much as this might seem obvious to state, it’s all too easy to slip back from mindfulness into unconscious behavior patterns. We all do it; we’re human after all. But this does also raise the question of how to be fluid to change while remaining true to the earliest teachings.

I recall attending a Vajrayogini empowerment in France about 10 years ago. As a lifelong vegetarian, living in France was already rather interesting as the French typically tend toward quite a meat-rich diet. Perhaps unsurprisingly then, during the tsok, a French volunteer was quite insistent that I eat the meat placed in front of me, regardless of my objections about my diet and ahimsa practice (as far as it was possible), which included abstaining from eating animals and industrialized dairy products.

Eating meat was part of the transmutation practice and needed to be done. That was the instruction. I decided that if I ruined it for myself by not eating, so be it, and I sent my respectful thoughts into the ether in the hope that it be understood, should anyone be listening. I discreetly opted to complete all other parts of the tsok, bar eating the meat. A week later, I found out that the following weekend the center had hosted a lama whose teachings had emphasized the importance of not eating meat as it caused suffering, and how the industrialization of the meat industry negatively impacted the environment and atmosphere. I admit to feeling slightly smug.*

Yet Cortland doesn’t labor modernity either. Rather than feeling like an effort to appease, this book is more like a real conversation on contemporary matters.

So what sets this book apart from many others in making the Buddhist teachings accessible to the curious who may be confused by all the techniques and terminology? I think that this will be a matter of personal opinion. What I appreciate about Cortland’s offering is how he does not lose us in a jungle of extraneous information, and nor is it bare-boned. He neither baffles nor infantilizes us with flowery syntax. It is not like reading an academic thesis, and it doesn’t lack for pithy instructions. Nor is it dry with a dictionary of terms (although there is still the standard and very handy glossary.)

In fact, this book seeks to be what Cortland acknowledges that he wishes he’d had access to when embarking on his own journey into the Dharma: a clear, open, friendly, and warm conversation that clarifies many of the most widely misunderstood terms and practices that a newbie may feel embarrassed about being unable to place into context.

Chapters are broken down into convenient subsections that lead the reader on a journey of understanding and introspection. And while some may disagree on the idea that there is a “progression” of the yanas, as if rendered hierarchically, I appreciated how one can see that they are not at all disparate. They are vehicles. Some people may feel more comfortable in a Mini Cooper, others in a large SUV, and others in a convertible. Yet the destination is the same. There cannot be competition between them as they are so different, and each shines depending on an individual’s needs at the time.

Cortland’s contribution to the Buddhist repository of knowledge is wonderful, especially for those new to Tibetan Buddhism. At a little over 200 pages, this volume isn’t overwhelming and neither is it a pocketbook. It’s a perfectly sized guide for those early on the path and well worth the read.

*Agree with me or not, I will not blindly follow a tradition that causes harm, whatever the symbolism. The packet that the meat came out of was certainly from an industrialized abattoir and guaranteed suffering. I didn’t appreciate the hypocrisy, and if my decision meant that my empowerment became void, so be it.

See more

A Meditator’s Guide to Buddhism (Shambala Publications)

Related features from BDG

Book Review: From Foundation to Summit by Orgyen Chowang

Book Review: This Fresh Existence – Heart Teachings from Bhikkhuni Dhammananda

Book Review: Gardens of Awakening by Kazuaki Tanahashi