What is the best state one can reach when practicing Chinese martial arts?

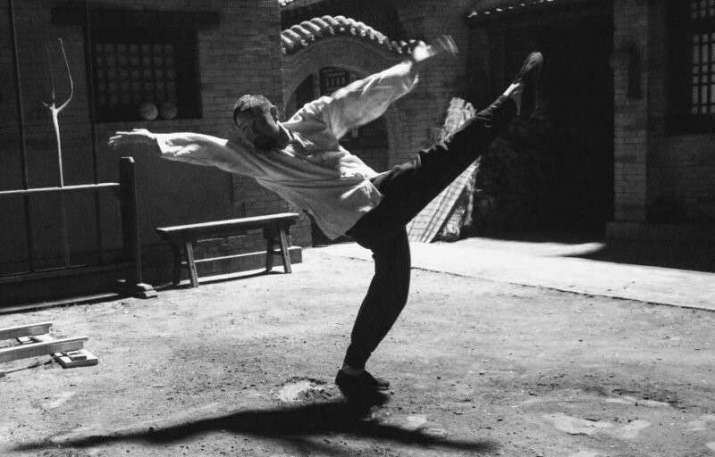

Stillness—your body is not moving, but you are moving.

Where are you in that state?

You are not standing on the ground; you are in the space, like an eagle soaring in the sky.

The above is a small excerpt from my conversation earlier this year with Xu Xiangdong (徐向東), a world-renowned master of Chinese martial arts, at the Bamboo Grove Vihara in the suburbs of Beijing. The vihara was recently set up by Venerable Master Miaojiang, abbot of the Great Sage Monastery of the Bamboo Grove on Mount Wutai. Having known Ven. Miaojiang for many years, Xu wanted to pay his first visit to the vihara when he was not travelling for work. Throughout our talk, Xu emphasized the significance of traditional Chinese thought.

“What we see in martial arts are just branches. The root of Chinese martial arts is Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. Can you hit hard a hanging rope? Can you stand still on a rolling ball? It is not about your physical strength, it is about your understanding of the object and the space,” Xu explained, with sparkles in his eyes. “Combat is not about what is in the form, but about what is in the mind.”

Born in 1961, Xu began his career in Chinese martial arts with the Hebei Wushu Team in Shijiazhuang, Hebei Province. At the age of 19, he earned the All-Around Champion title at the Chinese National Wushu Championship. A few years later, Xu was chosen as one of the leading actors in the 1984 film The Holy Robe of the Shaolin Temple (木棉袈裟) directed by Tsui Siu-Ming. Since then, while keeping his connection with the TV and film industries as a martial arts director and an actor, Xu has been exploring the world of martial arts in many directions: he studied at Beijing Sport University, served as a judge at the 1990 Asian Games, and taught Chinese martial arts in Paris while writing his doctoral thesis with French sinologist Catherine Despeaux. He was also invited to Brunei to teach martial arts to Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah.

While the description of martial arts might seem self-explanatory, Xu defines Chinese martial arts as “systematic research of the human body in traditional Chinese culture.” Essentially, it is about the relationship between mind and body. Xu elucidates: “Qi is the energy that moves the blood in your body, but qi follows what is in your mind. When you are happy, angry, or when you see someone you fancy, your body reacts differently. In Chinese martial arts, when you have the sword in your mind, you have it in your hand; when you don’t have it in your mind, even if you are holding a sword, that’s not a sword.”

This understanding dawned on Xu when he was learning martial arts with his first master, who was highly accomplished in neigong (內功, internal skills) and often quoted the Daoist Cannon. Part of Xu’s daily exercise at that time was to punch the master’s stomach 100 times. Xu was intrigued by the fact that while he himself felt exhausted, his master, who was in his 60s, remained unscathed.

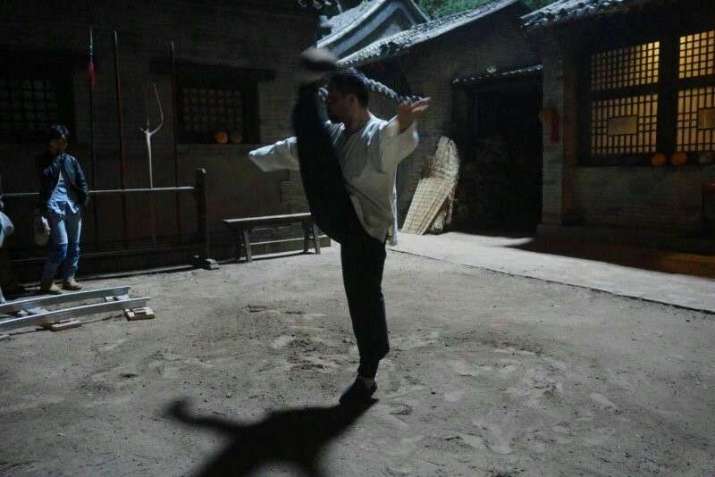

As a master of martial arts himself, Xu is best known for his innovation of the Eagle Claw Fist (鷹爪拳). While Xu trained in all styles when he was a member of the Hebei Wushu Team in the 1970s, he wanted to develop his own specialty. The choice of Eagle Claw Fist was inspired by Russian literature, particularly The Song of the Falcon and The Song of the Stormy Petrel by Maxim Gorky, which were popular in China during that period. For months, Xu would go to the zoo each week to observe the eagles. What Xu observed was not the form, but their spirit. To Xu, eagles are lofty and noble, and there are swords in their eyes. While the most powerful tiger can only crawl on the ground, eagles can fly in the sky, adding another dimension to space. The encaged eagles did not fly, but Xu could imagine how eagles soar and how he could fly like an eagle. That was how he invented many flying moves and infused the traditional style of Chinese martial arts with a new vitality.

Xu’s practice of Chinese martial arts has always been informed by Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. According to the Tao Te Ching (道德經), “In the pursuit of learning, every day something is acquired. In the pursuit of Tao, every day something is dropped. Less and less is done until non-action is achieved. When nothing is done, nothing is left undone.”*

In our conversation, Xu related that martial arts is also a process of deduction, from technique to no technique, from discipline to total freedom. In the light of zhongyong (中庸 the Doctrine of the Means) advocated by Confucianism, Xu commented that only by finding balance, does one have the pivot to move in all directions and to respond to external forces. As for Buddhism, Xu compares martial arts to the concept of using phenomenon to cultivate reality (借假修真), where one cultivates the mind through exercising the body. Xu recalled that when he first met Ven. Miaojiang, he was asked, “In which way do you see farther—with your eyes open or closed?” We all tend to believe that the eyes are the only way to see, but perhaps that’s how our mind is restricted by our body.

Almost all television series and films in which Xu has participated involve Buddhist and Daoist elements. Although the martial arts are highly dramatized through special effects in these works, Xu still enjoys acting, which he describes as a space in which he has no self. He has just finished filming Wu dong tian di (武動天地) with director Zhang Zhiliang as a tribute to practitioners in the early 20th century who tried to preserve Chinese martial arts. However, when asked whether he has any personal heroes, Xu responded, “My greatest respect is for ancient Chinese wisdom that has endured for thousands of years. It is not about any specific individual, it is just clever people who have elucidated or acted out traditional Chinese thought.” In the years to come, Xu plans to dedicate more time to studying Buddhism and Daoism.

* The original text is ”為學日益 為道日損 損之又損 以至於無為” from chapter 48, translated by Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English (1972).