Bhutan’s Paro College of Education hosted about 250 people from 25 countries for the Reimagining Education Symposium from 1–5 June, 2024. The event attracted former ministers of education, representatives of inter-governmental organizations such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, researchers, teachers, school leaders, wellness and mindfulness developers from all different traditions, the prime minister, and even King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, the 4th monarch of the Kingdom of Bhutan.

At the center point of nearly every panel and keynote was the question of how King Jigme Singye Wangchuck’s—the current king’s father who abdicated in 2006—innovative concept of Gross National Happiness (GNH) might permeate education systems in Bhutan and beyond. GNH is Bhutan’s more holistic answer to Gross National Product, and puts equal weight to other measures of success including sustainable and equitable socio-economic development; environmental conservation; preservation and promotion of culture; and good governance. The concept has energized a global community of thinkers to explore how education can be redesigned around these principles. Buddhism isn’t explicitly mentioned in these measures, although it can be assumed that as a Vajrayana Buddhist country, it is an imbedded part of the culture.

Students in Bhutan are taught Buddhism primarily in the home and in community ceremonial events such as tsechus, lunar new year, and other festivals. This exposure is augmented at school in their Dzongkha class. Dzongkha is the national language of Bhutan—along with English—but it is spoken in only about 30% of homes, primarily in the western part of the country, so it’s necessary for students to apply themselves to language learning in school. Dzongkha is most often taught by a khenpo (a senior monk) from the government’s monastic body, the dratsang. They use Buddhist texts as a basis for literacy. The script is the same as Tibetan.

According to many Bhutanese I spoke with, the pairing of the Buddhadharma with what can at times be a challenging language class does not always immediately spark students’ interests. But not all is lost. As one student said, “over the years when you start to really study and practice [Buddhism] with the right teacher, it starts to become relatable.”

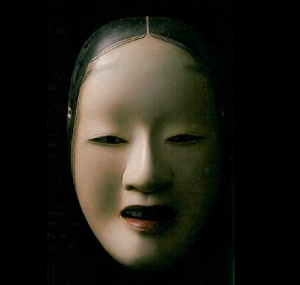

And many students are fortunate to have khenpos that can bring the teachings alive even in the language class. In addition to Dzongkha class, students start the day at most Bhutanese schools with a prayer to Manjushri, the god of wisdom. Bright orange, holding a book in one hand and wielding a blazing sword above his head, he is poised to cut through ignorance. Public school students in Bhutan recite a praise to him and a mantra, usually during the morning assembly.

After a group of students demonstrated this ritual one morning in the symposium auditorium, Paro College’s president took time to guide attendees through the translation of the prayer and explained the symbology and meaning of Manjushri. It was an illuminating speech. The mantra students chant every day is OM A RA PA CA NA DHIH, each syllable of which has a deep and fascinating meaning—read Jampal Dewé Nyima’s explanation on the Lotsawa House website. Interestingly, one Bhutanese participant bravely took the mic during the Q&A to say that hearing the president’s explanation was the first time he truly understood the prayer. The president agreed that there is a wonderful opportunity to bridge that gap in schools with more context and explanation offered around the ritual.

My experience working with Bhutanese teachers as a founding member of Lhomon Education in East Bhutan was that even a small amount of formal study or practice as adults can ignite that fuse ingrained in their being. It is ready and waiting right below the surface. Encountering living masters seems to be a highly effective spark. One Bhutanese friend said that meeting his teacher helped him, “start breaking those preconceived ideas of Dharma and culture,” that he developed in school. He is now finding refuge in the Dharma. But it can’t be assumed that all Bhutanese will have the favorable conditions of encountering a great master. Quite a few still heritage Buddhists relate to the Dharma as something external or cultural, something that offers comfort perhaps, but not always seen as a pathway or view that has a fascinating impact on everyday life.

Many people at the symposium—Bhutanese and foreigners—were working in the mindfulness space. There were workshops and keynote speeches on topics like Contemplative Education: Catalyzing Freedom, Consciousness, and Happiness in a Happytalism Framework; The Art and Science of Human Flourishing – An Evidence-Based Course that Supports Student Well-Being and Flourishing; Mindfulness for vulnerable children Only?; Integrating Mindfulness-Based SEL into Vietnam’s Education System: A Transformative Approach to Cultivating Happiness and Professional Success; Cultivating a happy heart in education through the Four Immeasurable Qualities; Enhancing socio-emotional learning and wellbeing in children and adolescents; Experiment Social Presencing Theatre to find Solutions for the Paradigm Shift in Education; Developing Mindful Organizations & Leadership: Insights on Wisdom at Work for Personal and Organizational Resilience and Mindfulness, Self- Compassion and Creativity – an inspiring light-footed path to Happiness.

Like most Bhutanese school children, participants started each morning with some variety of contemplative practice. A monk told me at lunch break that meditation was not a common practice in the past, it was reserved for serious practitioners who had completed a three-year retreat. But this has changed. Mindfulness was introduced in Bhutanese schools about ten years ago and there are now many various types of approaches to mindfulness practiced in the classroom there—from Thailand, Burma, India, Singapore, and the West, including Google’s Search Inside Yourself program.Introducing these practices seems to be a positive step. There is plenty of scientific and experiential evidence that mindfulness is good for children. Dr. Robert Roeser, a developmental psychologist from Penn State University, found that the most commonly assessed student outcomes of these programs were self-regulation, stress management, and psychological well-being.*

Bhutanese students also learn driglam namzha, or Bhutanese etiquette and morals that help maintain order, which rounds out their Dharma education. Considering the classic paradigm of prajna, samadhi and shila (wisdom, contemplation, and conduct), one could say that in Bhutan, prajna is introduced in the texts students are exposed to in Dzongkha class, samadhi is introduced in their morning mindfulness practice, and shila is covered by their driglam namzha study.

The prajna aspect of Darma is its most unique attribute. Buddhism promotes concepts such as ”emptiness of self,” “you are your own refuge,” “everything is impermanent,” and “do not rely on your senses alone” — radical ideas that, if truly understood, can lead to liberation in this lifetime—another concept that is not promoted by other organized religions.

The concept of organized religion is probably the biggest obstacle to introducing the Dharma in the school environment globally, even in Buddhist countries like Bhutan. This categorization is problematic and often debated. Some might say Buddhism is a “disorganized religion” or not a religion at all. It could be called a “strategy”, or a way of life driven by these radical ideas. If educators could consider presenting the Dharma to children in this way, rather than as a religious doctrine, it has more of a chance of coming alive.

Which would be amazing. There is so much that the Dharma has to offer children. Meaningful connections can be made by introducing it in fresh, age-appropriate ways. Ancient wisdom is still fully relevant to children because it is based on rigorous examination of the mind. When the Buddha taught, he presented his truths as an invitation not as a dogma. He invited students to really chew on these ideas before adopting them. That critical thinking is completely in alignment with the best practices of modern education. Nevertheless, Buddhism is sometimes presented as a stiff set of rules for moral conduct or archaic poetry. It’s something to watch out for.

The strategy to incorporate the Dharma into the education system in Bhutan by way of atmospheric transmission—relying on the strength of the Dharma as a given—may just work. Because of its veracity, flexibility and adaptability, the Dharma has managed to remain relevant for nearly three millennia and it will be interesting how it adapts to a modern time in an ancient culture.

“Dharma is so ingrained in our culture and traditions that it’s become a way of our life,” said one Bhutanese friend. He explained that Bhutanese live and breathe the Dharma, which if truly applied would lead people to adopt those pillars of Gross National Happiness from a deeply personal and natural place. On the other end of the spectrum, the experts who come to Bhutan from around the world to research the impact of GNH education on teachers and student well-being and holistic development will have plenty to work with.

* “Beyond All Splits: Envisioning the Next Generation of Science on Mindfulness and Compassion in Schools for Students.”Mindfulness 14(7):1-16. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365321521_Beyond_All_Splits_Envisioning_the_Next_Generation_of_Science_on_Mindfulness_and_Compassion_in_Schools_for_Students

See more

Reimagining Education From a Gross National Happiness (GNH) Perspective

Gross National Happiness (Wikipedia)

tsechus (Wikipedia)

The Meaning of the Six Syllables of the King of Vidyā-Mantras, the Heroic Lord Mañjuśrī

(Lotsawa House)

Lhomon Education (Khyentse Foundation)

Driglam Namzha: Bhutan’s Code of Etiquette (University of Virginia)

What Is the Threefold Training? (Lion’s Roar)

Related features from BDG

From Bhutan to Korea: Reflections of a Female Monastic on the Buddhist Path

Introducing the Buddhadharma to Non-Buddhist Parents of School-age Children

Gelongma Dompa (dgeslongma’i sdom pa): The Blessing of Bhikshuni Ordination in Bhutan

Children in Lockdown: The Need for a More Mindful Approach to Education

For Our Children’s Sake: Dismantling Racism and Bias in Schools

Related news reports from BDG

Engaged Buddhism: Ven. Pomnyun Sunim and JTS Korea Support Buddhist Nunneries in Bhutan

Buddhist Education: Middle Way Education Announces New Director

IBC Invites Delegation of Senior Buddhist Monks from Bhutan to Visit India

Buddhist Monks in Bhutan Join Movement to Raise Awareness of Sexual Health and Rights