Jacqueline Kramer, author of Buddha Mom-the Path of Mindful Mothering and 10 Spiritual Practices for Busy parents, has been studying and practicing Buddhism for over 30 years in the Sri Lankan Theravadin tradition and Zen for 8 years. When she became pregnant with her daughter she applied Buddhist principles to her pregnancy, birthing and mothering to good effect. This led to her books and teachings. In 2008 Jacqueline received the Outstanding Women in Buddhism Award at the U.N. day for women in Thailand for her work teaching Buddhism to mothers. She is the director of the Hearth Foundation – www.hearth-foundation.org, which offers online lay Buddhist practice classes designed for mothers, a monthly newsletter and other resources for today’s mothers seeking spiritual support and inspiration. Hearth has students in Australia, Argentina, New Zealand, Europe, the US, Canada and throughout the world. She is past vice president of Alliance for Bikkhunis, has been on their editorial board, and actively supports female monasticism. Jacqueline is currently studying koans with John Tarrant, writing on femininity and Buddhsim for Turning Wheel, and other magazines, and developing teachings informed by feminine spirituality. Jacqueline lives in Sonoma County, California.

—

This article was originally published as a dharma talk in Hearth Magazine’s December 2009 edition.

As some of you may know, besides the work I do teaching Buddhism to mothers, I am also working to support female Buddhist monastics. The link between these two concerns is that both efforts support women’s full flowering on their spiritual path. Recently there have been some events related to bhikkhunis that are of pertinence to women, regardless of their religious orientation.

First a little background. A bhikkhuni is a female monk in the Theravadin Buddhist tradition. In Korea and Taiwan, countries that practice Mahayanin Buddhism, the nuns are called bhikksunis, but both bhikkhunis and bhikksunis follow the same structure, or monastic rules laid out in the Vinaya. The Buddha’s teachings are placed in three sets of writings, called the Three Baskets. They are the Suttas, or stories of the Buddha’s teachings, the Abhidhamma, which lay out Buddhist psychology in great detail, and the Vinaya, which are the rules of conduct for the monks and nuns. These are the rules that support both male and female monastic communities.

In the Buddha’s time there were both female and male monastics. In fact, the Buddha, towards the end of his life, said that Buddhism would not take hold in a country until there were female monastics, male monastics, laywomen and laymen who are all well versed in their understanding and practice of the dhamma. This four-fold sangha was established by the Buddha and took root in the countries where Buddhism migrated in the early days. The story begins to get complex and disputed at this point. Due to war and internal affairs the bhikkhuni orders died out in Sri Lanka and other countries. There is dispute about whether or not there ever were bhikkhunis in Thailand but if there have never been bhikkhunis there than, according to the Buddha, Buddhism never really took hold as envisioned by the Buddha. There is much discussion about the verity of the facts here. Honestly, it starts sounding to the non-scholar like “How many angels can dance at the tip of a pen?”

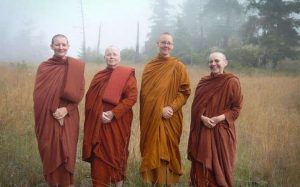

Fast forward to the 21st century. In Korea and Taiwan the bikksuni order is thriving. Yet the Theravadin bhikkhuni orders have been undergoing difficult birthing pains. Thanks to the support of some fair minded bhikkhus, male monks, and some very brave and determined women, the bhikkhuni order in Sri Lanka has been reestablished and is growing, although it does not yet enjoy governmental recognition. Burma and Thailand are another story. In these countries there have been local laws developed to prohibit women from ordaining. Burma, being a closed system, does not currently allow for any movement at all on this issue. However, in Thailand there have been recent events that challenge the all male monastic system. Last month Ajahn Brahm, a bhikkhu ordained in the Thai forest tradition of Ajahn Chah, went ahead and ordained four women in his monastery in Australia against the wishes of the Thai elders and many of the western monks trained in the Ajahn Chan lineage. For this he was excommunicated and the WPP, who voted for this excommunication as well as declaring the female ordinations null and void. In the same month Ajahn Sumedo of England, a western monk, who is also ordained in the Ajahn Chah tradition, developed his “5 Points” which basically puts female monastics in a lower position than male monastics and does not allow the women to become fully ordained bhikkhunis. The significance of this is that a western monk is not only importing the old rules excluding women but creating new ones.

As Buddhism comes to the West it is essential that we do not import the old, cultural misogynistic views along with the beautiful, relevant teachings of the Buddha. The Buddha was a civil rights advocate in his day. By ordaining “untouchables and women” he went as far as he could go at the time to include all people. In our age women all over the world are being lifted up high enough to stand side by side with their brothers. Women are becoming ordained as priests and rabbis in the western traditions. In Buddhism women are also moving into roles of spiritual leadership and have similar battles to the battles their western sisters have.There is much back and forth about laws and traditions but bottom line, women are moving into positions of equality and, predictably, many Buddhist males who enjoy positions of power are fighting this movement towards equality. As St. Augustine wrote, “An unjust law is no law at all.” In the highest regards no laws were broken when Ajahn Brahm ordained the four new bhikkhunis and, actually, the Buddha’s laws are being broken wherever females are excluded from full ordination.