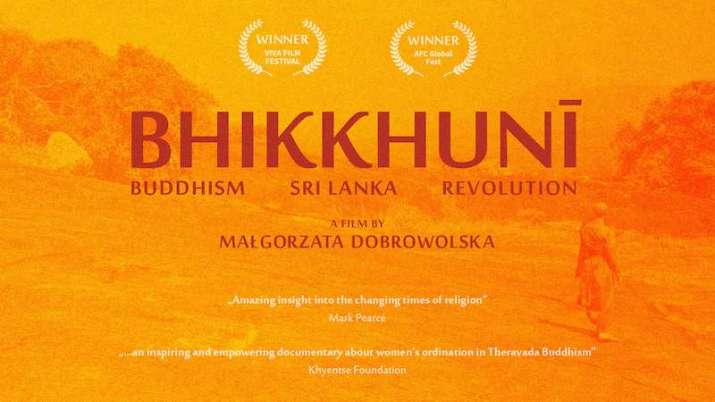

Many of the most dramatic episodes concerning Theravada women’s ordination have occurred in Thailand, where much press attention has focused on prominent figures like Ajahn Brahm (now expelled from communion with the sangha founded by Ajahn Chah) and Ven. Dhammananda, two of the standard-bearers for the female ordination movement. However, it was actually in Sri Lanka that the politics of female ordination first truly succeeded in 1998, with the ordination of a group of Theravada bhikkhunis assisted by Chinese nuns following the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya. Yet this was only the beginning of a long struggle for full recognition of women as fully ordained teachers in Sri Lanka. It is this struggle, with all its progress and obstacles, that filmmaker Małgorzata Dobrowolska charts in Bhikkhunī – Buddhism, Sri Lanka, Revolution.

For as long as she remembers, Polish-born Małgorzata has been haunted by the unequal status between men and women in the Roman Catholic Church, the spiritual tradition in which she grew up. “Even as a child I was wondering why a woman couldn’t be ordained as priests. I realized later on that this inequality is present in all major religions of the world. I started searching for women who would break free from these patterns,” she says. As she began to build a professional identity as an activist and documentary filmmaker focusing on the stories of women, her Buddhist line of enquiry initially led her to Thailand.

“In 2015, I was in Thailand at Songdhammakalyani Monastery. This is the first bhikkhuni monastery in this country,” she says. “The head of the monastery is Bhikkhuni Dhammananda, the first fully ordained Theravada nun from Thailand. Staying in this monastery made a great impression on me. I met a community of exceptional women who are not recognized by the government and most Thai monks, along with a portion of laypeople. The origins of the Thai bhikkhuni order are in Sri Lanka. It was there that Ven. Dhammananda, one of the protagonists of my documentary, took full ordination in 2003.”

For Małgorzata, filming was a great adventure: “Of course, sometimes I had difficult or stressful situations. I came to Sri Lanka all by myself. I did not know this country well. The moment I was flying out from Poland, I did not know if any of the nuns would agree to be the protagonists of this documentary. It turned out that my concerns were completely invalid. The nuns received me very warmly and I immediately felt at home. They were very eager to share their stories, their fears, and their goals with me. They introduced me to their world. I felt that it was also important for them, that they could tell their stories themselves, that the history of re-establishing the bhikkhuni order would be recorded.”

Sri Lanka played a key role in the history of the creation of the bhikkhuni order after Ashoka the Great’s daughter, the nun Sanghamitta, established the lineage on the island. “Nowadays it is even more important in the rebirth of the lineage in South Asia,” Małgorzata observes. “Many women who can’t undergo full ordination in their countries come to Sri Lanka to become bhikkhunis, then return to their homelands afterwards. I was very fortunate to be able to record the International Theravada Bhikkhunī Ordination 2016 on film. It was a historic event. Women from Bangladesh, Thailand, and Vietnam came from their respective countries to be ordained. The Bangladeshi group of women was the first batch of Theravada bhikkhunis from their country. The leader of this group was a nun called Gautami, who became the first Buddhist bhikkhuni from Bangladesh.”

The film was shot in Sri Lanka, but the main characters are women from three different countries—Ven. Kusuma from Sri Lanka (ordained in 1996 in India), Ven. Dhammananda from Thailand (ordained in 2003 in Sri Lanka), and Ven. Gautami from Bangladesh (ordained in 2016 in Sri Lanka). They are all the first women in their respective countries’ modern histories to become fully ordained nuns.

Even in Sri Lanka, however, the idea of ordaining female monastics has had a mixed reception. “The situation for bhikkhunis in Sri Lanka is by far the best in the context of countries where Theravada Buddhism is the main religion. Some of the monks in Sri Lanka support the ordination of women,” Małgorzata explains. “It is thanks to them that the bhikkhuni line was successfully re-established, and new international ordinations are being organized. But still the government and a large number of monks do not recognize bhikkhunis. Certainly the Sri Lankan government does not throw women into jail for trying to become fully ordained nuns, and even the most hardcore orthodox monks don’t force women to disrobe. So one might say the island is moderately tolerant toward the bhikkhuni movement.”

The pace of progress is not entirely attributable to Vinaya concerns or sexist attitudes. There are genuine institutions that allow for “grey” areas to overlap the more distinct roles of “laywomen” or “bhikkhunis,” such as the dasa sil matas, who are living in accordance with ten precepts but not considered ordained monastics. As the dasa sil matas idea is a relatively recent import from Myanmar (since about a century ago) and is similar to the mae chee institution in Thailand, Małgorzata believes that this is not a sustainable situation in a country such as Sri Lanka, where female ordination along Theravada Vinaya lines has been reconstituted. “It is similar to waiting for a doctor in a lobby, without getting a chance to actually walk into a doctor’s office,” she notes.

Małgorzata argues that the most important thing is the recognition of the bhikkhuni order by laypeople and awareness of the situation of the women’s order. “I believe the crucial thing is education about the history of bhikkhunis, as well as raising awareness of the importance of the fact that the restoration of women’s ordination has been achieved,” she observes. “This applies not only to Sri Lanka, but to the whole world.”

At present, Małgorzata is distributing the film, which she concedes is the most difficult task of the filmmaking process. “In modern society, we are being bombarded with advertisements and offers at every turn, so it is very difficult to get through this commercial noise and offer audiences a full-length documentary about the revival of women’s ordination in Theravada Buddhism. Still, this is a very important topic and people do not realize that in Theravada Buddhism—one of the oldest and largest Buddhist traditions—there has been such a huge breakthrough or even revolution. After a thousand years, women can once again be fully ordained. The sangha is returning to the state that the Buddha wanted. It is very important to be aware of it and to support it.”

To learn more about Bhikkhunī – Buddhism, Sri Lanka, Revolution, visit the film website at bhikkhuni-film.com.

See more

Bhikkhunī – Buddhism, Sri Lanka, Revolution

Mistrzynie życia duchowego (Facebook)