In the sacred conversation between scholarship and devotion, Prof. Klaus-Dieter Mathes emerges as a bridge—a seeker who defies boundaries and weaves together the threads of the sacred Dharma and rigorous scholarship. In the picturesque medieval city of Ávila, Spain, I had the privilege of sitting down with Prof. Mathes to delve into his lifelong dedication to the translation of Buddhist manuscripts. He is a beacon in the field of Buddhist studies and has recently joined the University of Hong Kong’s Centre of Buddhist Studies (CBS).

At CITeS’ “3rd World Meeting on Teresian Mysticism and Interreligious Dialogue” in July, I found myself captivated by Prof. Mathes’ discourse on “Meditation on the Deity in Tibetan Buddhism.” His kind smile, coupled with a heartfelt tribute to his Mahamudra master, Venerable Thrangu Rinpoche, immediately caught my attention. Rinpoche, too, holds a special place in my heart as my beloved teacher.

Hailing from Vienna, Prof. Mathes holds the prestigious position of chair of Buddhist Studies at the University of Hong Kong. This rare chair symbolizes the fusion of spiritual devotion and critical scholarship. In 2023, on arriving in Hong Kong, he received the eminent and prestigious Yuen Hang Memorial Trust Professorship. This allows him to explore ancient Tibetan philosophical texts and the reception of late Indian Mahayana Buddhism in Tibet.

Our conversation unfolded like a sacred journey. Prof. Mathes guided us through the history of his personal Buddhist translation activities, drawing from his seven years of dedicated service as the director of the Nepal Research Centre and the Nepal-German Manuscript Preservation project. Their mission was to safeguard and explore the treasures of Tibetan manuscripts nestled in Kathmandu and the Nepalese high mountain regions.

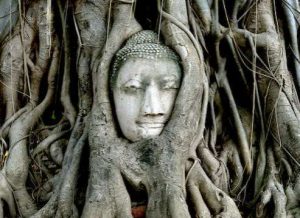

As he shared his memories, I joined him by first asking about his visit to Samye Monastery—the cradle of Tibetan monasticism and translations. Samye was the first imperially sponsored institution during Tibet’s first diffusion to offer a systematic translation of Buddhist texts. Rooted in the Indian gradual path of late Buddhist philosophy (Yogacara and Madhyamaka), Samye stands as a testament to the legacy of Guru Rinpoche or Padmasambhava. Its foundation, inspired by the sacred Otantapuri in northern India, rests on the Vairocana Mandala that the Yarlung dynasty, imperial Tibet’s ruling family, worshipped.

“The Vairocana Mandala in Samye Monastery was very common, even among non-tantric monasteries,” observes Prof. Mathes. “It has provided the blueprint of many temples and buildings all over Inner and East Asia. The mandala represents the pure vision of ourself and the surrounding area as buddhas and their divine mansions. The Five Great Buddhas in the center and the four cardinal directions thus represent the transformation of our five skandhas into the five types of wisdom in Vajrayana Buddhism. The old Tibetan kings considered themselves to be Avalokiteshvara, at the center of such a mandala. So the whole state was defined as a divine mandala palace.”

From Samye’s hallowed halls, we traced Prof. Mathes’ academic journey. In Wachendorf, Germany, he immersed himself in the Buddhadharma at the Kamalashila Institute. Later, he moved to Nepal. He proudly shared his connection with the late Ven. Thrangu Rinpoche. During his seven years in Kathmandu, Prof. Mathes resided near Thrangu’s Namo Buddha Monastery. This was a serendipitous proximity that fostered a profound bond with Thrangu Rinpoche. Tulku-la, as I like to call the late Rinpoche, radiated warmth with his perpetual smile. Across continents, their shared passion for preserving Buddhist manuscripts forged a unique kinship. Despite Prof. Mathes’ foreign origins, Rinpoche unwaveringly supported his work, even opening his private collection of manuscript block prints for mutual learning and validation.

As Prof. Mathes recounted these milestones, I recalled Rinpoche’s kindness, diligence, and unwavering commitment to safeguarding the Dharma. The Namo Buddha Publications, established by Tulku-la in 1989, echoes this dedication—a beacon disseminating wisdom to practitioners worldwide.

In the course of my conversation with the professor, I learned that Buddhist manuscript translator, more commonly known as lotsawa, is a highly revered status in the ancient Buddhist world. I think two luminaries, guardians of wisdom in Buddhist history, are significant lotsawa: Lochen Rinchen Zangpo (958–1055) and Xuanzang (602–64).

Amid the Himalayan peaks of Ladakh, the legacy of Lochen Rinchen Zangpo, known as Mahaguru, transcended mere translation. He was an architect of enlightenment, constructing more than a hundred monasteries in western Tibet. Among them, were the Alchi, Tabo, Poo, and Rinchenling monasteries, which functioned as vibrant hubs of study, practice, and the preservation of Buddhist wisdom. Rinchen Zangpo’s tireless translation work connected ancient Sanskrit texts to the Tibetan heart, disseminating the teachings of the Buddha across the Himalayan kingdoms.

In seventh-century China, Xuanzang, up against imperial disapproval and effective house arrest, embarked on a legendary odyssey to India. At Nalanda University and other places, he imbibed the Mahayana scriptures, carrying their physical texts back to China. In Chang’an, under Emperor Taizong’s patronage, Xuanzang established a translation bureau. He meticulously rendered 657 Indian texts into Chinese, which revolutionized Buddhist scholarship. His Yogachara legacy as the “Master of the Three Baskets” (Tripitaka Master) illuminated the path for generations to come. Thanks to masters such as Xuanzang, we can really speak of a “Sinicized” Buddhism for a local population that begins in the Tang dynasty.

The tireless efforts of these two lotsawas bridged cultures, spanning the ancient pathways of India and China, and are still celebrated today.

What struck me beyond Prof. Mathes’ unwavering commitment to practice was his veteran status in the Germanic Buddhist academic circle. Under the tutelage of the eminent professors Dr. Michael Hahn of Marburg University and Dr. Lambert Schmidthausen of Hamburg University, he delved into the rich tapestry of the Yogachara tradition in Indian Buddhism. Buddhist studies, often viewed as a study of Asian culture and philology, demanded impartiality, an “outsider” perspective. Yet Prof. Mathes shattered conventions by declaring his Buddhist identity.

“Times have changed,” he says, “but in the 1980s, it was even considered a disadvantage to be a Buddhist because it means, you know, you don’t have the necessary critical distance to what you’re studying. So I received some strange reactions by officially declaring that I’m a Buddhist, and professors at university were a little suspicious about whether I would be able to work academically in a proper way.”

Balancing tradition and academia, Prof. Mathes embraced both the sacred Dharma and scholarly rigor. Today, it’s no anomaly for professors to be Buddhist practitioners—an evolution that resonates. As the saying goes, practice makes perfect. An “insider” perspective can also be beneficial. Engaging with the Dharma adds depth to the study of religious texts.

Prof. Mathes transcends binaries, surfing the currents of non-duality and emptiness. His legacy illuminates paths for devotees and scholars alike. Amid Hong Kong’s vibrant skyline, he invites us to go beyond the ordinary, inspiring us to heed our heart’s calling with dedication and merit.

Related features from BDG

Buddhistdoor View: Interfaith Is Inherently Worth It

Related news reports from BDG

3rd World Encounter of Teresian Mysticism and Interreligious Dialogue Explores Carmelite and Buddhist Mysticism

Second Edition of the Buddhist Film Festival of Catalonia, Spain to be Held in October 2024

Related blog posts from BDG Tea House

Yarlung Rising: The Imperial Cult of the Sun Buddha, with Dr. Giorgios Halkias