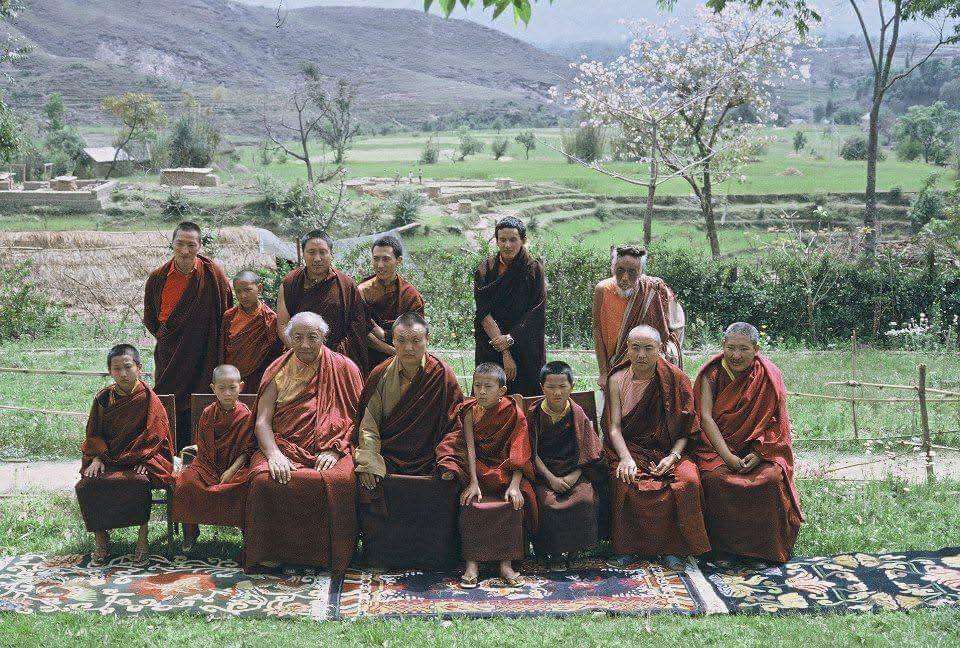

Image courtesy of Siddhartha’s Intent

Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche is a senior teacher of the Vajrayana tradition. In this interview, he looks back over five decades of his vocation as a religious leader and teacher, offering some candid thoughts about what it is really like to be a rinpoche.

Buddhistdoor Global (BDG): What is it actually like being a rinpoche, and how is that changing?*

Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche (DJKR): Just like everything around us, things have changed so much in the Buddhist world. Even the image people have of Buddhism, and especially Tibetan Buddhism, is very different today than it was in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. And so is people’s understanding of the whole purpose of having tulkus** and rinpoches, and how they should be trained.

In our day, we had our challenges. Many of us grew up eating potatoes month after month, while rinpoches today can go to five-star restaurants of their choice and enjoy buffet feasts. This is not to say that today’s rinpoches have a great life. They just have totally different challenges.

We human beings are very strange creatures. We want to be in the limelight and we dream of becoming famous public figures. If only we knew what a heavy price that carries.

Reincarnate lamas might be seen as holding very privileged positions, but it’s important to understand that most of us rinpoches, especially in my generation, did not choose that title or strive or work for it. Most of us were placed in that position without much choice and without knowing what was going on.

But then you may say: “Well, now you do have a choice.” That’s easier said than done though, especially when you live in a very complicated society that has lots of cultural nuances and expectations, and when you’ve been groomed your whole life to think and act a certain way.

As human beings, how we grow up and how we’re raised for the first 10 or 20 years affects the rest of our life, especially when that early period is really cloistered, restricted, and shielded from everyday life. By the time rinpoches are 20 or 30 years old, they literally don’t know what else to do or how to do anything other than what they’ve been groomed to do. Sadly, that’s often just sitting on a throne, offering a totally fake smile, and pretending to be an unmoving statue. In fact, there’s even a Tibetan saying that you have to “sit like a golden statue.”

In many ways, things nowadays are very different from when I was raised. Today, it’s often the case that parents and relatives are overly eager to have their child recognized as a rinpoche. As well, we often see rinpoches blamed for being spoilt and taking advantage of students. To an extent, some of those accusations may be true.

But the blame for being spoilt and living completely in a bubble shouldn’t be laid entirely on the rinpoches. In fact, the blame should be placed first and foremost on Tibetan society, on the Tibetan high lamas, and especially on the stakeholders in the tulku system, who either totally ignore or choose to remain ignorant of the reality of change over time and in the world. Too often, they are like ostriches, with their heads buried in the sands of old and archaic cultural traditions that actually have nothing to do with the Buddhadharma.

As a result, the whole system has never been updated to train tulkus for the times in which they now live. That would in fact be difficult to do, because the way that rinpoches are trained is very organic and localized, and there is no formal system or institution to train tulkus in the way that Eton trains the English elite.

But it’s not just Tibetans who are at fault in all this. So many non-Tibetan Dharma students are fascinated by these young rinpoches sitting on thrones and clad in brocades. Those devotees generally make a really big deal of bowing down before these kids and interpreting every childish gesture as profound and meaningful.

Just put yourself in the shoes of these rinpoches. From the time you are three or four years old, hundreds of people take your photo, publish it, enlarge it, and put it on thrones and on their shrines. They worship and praise you, stand when you come in, smile at you, bow to you, wow at you, and put you on a pedestal. They refer to you as their teacher and protector, and treat you as a completely sane, moral, pure being. Although you’re just a kid, these devotees make you believe that in all matters, you’re the one who knows best.

This is your life from early childhood, and it goes on like that for a decade or more. On the one hand, you’re the authority so you always get your own way and no one dares go against you. On the other hand, this whole time, without ever choosing it, you’re expected to look, think, and act in certain ways, and not to look or act in other ways. You’re virtually imprisoned in a golden cage just because society gave you a title and a role that you never chose.

Imagine you’ve grown up like this, and now you reach the age of 15 or 20 and suddenly everything changes. You reach puberty, your hormones start raging, you are sexually attracted to people and images, and you become an adult. Yet, with all of this and your hormones going wild, you’re still expected to behave and act in a saintly manner, as if you’re in some way divine.

Even if you want to have your own life just for a day—to be yourself, alone, doing your own thing—you can’t, because by this time your parents, your so-called disciples, and your whole society have made sure that everyone knows your face. Your photographs are everywhere, and every movement you make is the talk of the town.

How would you feel in this situation?

Yes, at the outer level, K-pop stars, movie idols, and other celebrities are in a similar situation. But they’re not expected to be pure spiritual guides, and they at least chose their career. Most of these child rinpoches never had a chance to choose that life.

Frankly, the parents and caretakers of many of these young rinpoches are destroying the lives of human beings without even raising competent Dharma teachers. Rinpoches today have only a tiny fraction of the strict training that we used to receive. Today’s young rinpoches have weekends, winter holidays, summer breaks, and outings to Goa, Bangkok, and even Hawaii, but no proper training. In my day, we didn’t even know what a weekend was.

So on the pretext of modernization, strict and rigorous training is now disparaged and replaced by all kinds of pampering, worship, and parental ambition, which do not help in the rinpoches’ training at all. Of course, there’s no excuse for abuse in the name of strictness. But it seems well overdue to take a close look at what we have lost by doing away with the more thorough training of the past. Unfortunately, the way things are going, such a re-examination would seem highly unlikely.

BDG: Will the tulku system continue?

DJKR: Yes. I think the tulku system will continue for all kinds of reasons—both right and wrong. But that is not really the issue, and most of the discussions about whether or not the tulku system should continue really miss the point. The real issue is the need to update and completely rethink how we train not only the rinpoches, but also the khenpos,*** teachers, and other key Dharma stakeholders.

This rethinking raises many key questions, like whether or not rinpoches should be enthroned and whether they should even have attendants and an entourage. For instance, when close friends tell me about a newly discovered tulku, my first reaction is to tell them never to mention it. I tell them to hide all the lamas’ predictions and endorsements, and just to ensure that the children get proper training. Once rinpoches are well trained, reach a certain age, and are able to teach, then by all means pull out all those endorsements as ornaments.

At present, we do totally the opposite. We flash all these big endorsements, recognition letters, and fancy seals just to prove that great lamas have recognized the new rinpoche. Sadly, many of these old lamas who recognize rinpoches don’t know too much about the way things are in the modern world.

The devotees, students, and sponsors of a rinpoche’s past incarnation also have a huge responsibility not to spoil the new rinpoche, especially when he or she is young. Of course, that’s going to be really difficult. As human beings, it is those we adore that we most like to please.

Making these changes is particularly difficult for those who have been told that they must see the new incarnation just as they did the previous one. To see a toddler who can’t even wipe his own nose as identical to his mature, learned, accomplished previous incarnation is actually a form of personal mind training for a Vajrayana practitioner.

This is actually not very different from the practice of thinking of your next-door neighbour as a sublime being. So if all this is taken as mind training for an individual practitioner and doesn’t go beyond that, then it’s perfectly fine. The problems start when the young toddlers are expected to perform like their previous incarnation—to hold the lineage, to propagate and preserve the Dharma, and therefore to communicate and interact with others. Those communications may include everything from having good table manners to being sensitive to others’ feelings. These children have had no training to prepare them for that.

Even if you do have plans, ambitions, and expectations for the toddler to have such an esteemed status in the future, you at least have to create the causes and conditions for that to happen. Instead, the toddler’s parents, teachers, and the whole of Tibetan society are doing the exact opposite by not letting the child have any genuine human experience. That’s like clipping the wings of a small bird and then expecting it to fly like an eagle.

In this absurd situation, doomed to failure, it is mind-boggling that in the last 40 years tulkus are mushrooming everywhere, more than at any time in Tibetan history. And it’s even more ludicrous that we expect all these toddlers to run the world without the most basic equipment.

It’s these unrealistic expectations that create the problems. Just to communicate with others requires an understanding of what others feel and think. But most of these rinpoches have had no hands-on training or experience simply in relating with people. Mostly, all they have is some grand intellectual or academic theory that all beings have buddha-nature or that one has to be compassionate to all sentient beings.

For instance, when rinpoches and lamas are growing up, they don’t consider that the money a sponsor is spending to buy them lunch has actually been hard-earned and carefully saved, often with a great deal of hardship, blood, sweat, tears, and all manner of difficulties.

Now, to come back to your question on whether the tulku system should continue, I have to say yes—I still see a lot of use in it for at least another two decades, if not longer. It’s already an established institution with proven benefit, and if it’s properly monitored and updated, it can continue to be very beneficial. So I certainly don’t see the whole tulku system being so outdated that it should be thrown away. But major change is certainly necessary.

BDG: You have been a rinpoche for more than 50 years. Does the job get any better or easier as you get older?

DJKR: Well, I’m certainly not perfect, but at least my generation was blessed with some of the greatest teachers, who inspired us so much through their amazing example. That kind of inspiration and example, in my opinion, is really fading in this day and age.

I think what you hear and see when you’re young really has an impact on your mind and on your whole life. To give just one example, my mother and my teachers really scolded us if we wasted even one grain of rice, and they always told us how hard-earned such offerings were. That mindset was planted in us from a young age. That time was very dire and precarious—materially, politically, and in other ways. Ironically, I now take those difficulties as a blessing.

Another example that really had an impact on me is that my teachers, like Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, never rejected or ignored anyone, from the most ordinary-seeming people to the supposed elites. That still makes me feel guilty whenever I ignore people just because I’m so lazy. In fact, I regard that feeling of guilt as my masters’ blessing. These days, things have degenerated so far that I don’t think the next generation of rinpoches will even feel guilty.

Many people don’t seem to realize how hard it is to be a rinpoche, especially in this current era, where all spiritual leaders are looked at with some suspicion—often with good reason. Particularly in societies where Buddhism is new, we’re often even seen as cult leaders.

At the same time, when people do see a rinpoche as a genuine spiritual guide, that also brings its own baggage. So-called disciples may open up their hearts and minds to you, but often, whether consciously or unconsciously, they see you as their father, brother, husband, lover, or companion, which creates lots of expectations and assumptions as well as fear. That in turn can make interactions with people incredibly fraught and scary. Continual projections are exchanged between a rinpoche and his or her disciples, who constantly interpret their rinpoche’s moods and preferences in their own ways.

So in the midst of respect, awe, love, and devotion, endless projections are also made and discussed. Students may have a strong desire for acceptance and a fear of rejection. Or if their rinpoche looks unhappy one day, they may say it’s because of something they or others did, when in fact he or she might just have the flu.

So whatever a rinpoche says or writes, even making a little joke, sending a text, or saying something innocent like “I miss you” can be interpreted and stirs up people’s imaginations. When things don’t work out according to both sides’ expectations and assumptions, and when things go wrong as they almost always do, it can get very nasty. And today, of course, we have social media, which multiplies all the miscommunications and make them so much worse.

Rinpoches and lamas, especially of the next generation, need to be coached in all of this. I’m not saying we should tell them to stay away from social media, to remain aloof, and not to communicate or be in touch with people. That’s each rinpoche’s individual choice. But whatever a rinpoche does, simply because of who he or she is—a privileged person and a public figure—there will be consequences for which they need to be prepared. As long they’re aware of that and can take the pressure, it’s entirely up to these rinpoches whether and how they relate with people. But, presently, most young rinpoches are not prepared or aware. I have met at least two of the younger rinpoches who were on the verge of killing themselves because they just couldn’t handle that pressure.

These young rinpoches need people they can talk to and with whom they can share their ups and downs without their being scandalized or passing judgement. Basically, they need real friends. Among many other things, they need “people training.” And they need training in how to relate with the opposite sex. In fact, they need sex education.

BDG: Do you want to leave us with any parting words on this subject?

DJKR: Well, to come back to your first question, what is it actually like being a rinpoche, it’s nowhere near as easy or as glamorous as people think. You find out the hard way that you’ve been signed up by others to completely give up your privacy and to spend your life navigating a minefield of people’s emotions, projections, expectations, labels, interpretations, and more.

But at least, when I look back on my upbringing, I and other young rinpoches of that generation were given the opportunity to meet and receive the most precious teachings from some of the most amazing and accomplished masters ever to walk the face of this planet. That gift alone makes everything worthwhile, and even turns the biggest obstacles and challenges into a joyful chance to try to repay our teachers’ extraordinary kindness.

I can only hope that the next generation of young rinpoches, tulkus, and khenpos will emulate those great examples and put every effort into receiving and, most importantly, into practicing the teachings of the Buddha, so that they can protect those teachings and practices and propagate them for the future.

* Rinpoche literally means “precious one,” and in Tibetan Buddhism generally refers to an incarnate lama or highly respected teacher.

** Penor Rinpoche defines a tulku as “a reincarnation of a Buddhist master who, out of his or her compassion for the suffering of sentient beings, has vowed to take rebirth to help all beings attain enlightenment.”

*** Khenpo is a title given in the Nyingma, Sakya, and Kagyu schools to a learned scholar who has completed rigorous studies in Buddhist philosophy.

Wonderfully articulate article shining with clarity.