The journey from the touristic bustle of the northern Indian town of Manali into the remote valleys of the Himalayan mountains in northeastern Himachal Pradesh—especially the Spiti Valley—is a marvelous but time-consuming ascent: at least a 12-hour ride on a local bus for a little less than 120 miles traveled!

We first scaled Rothang Pass before reaching Kunzum Pass, which sits at an altitude of 14,931 feet and is the portal to the Spiti Valley and its forest of prayer flags—an inspiring vista honoring the glaciers before us. Within the unfolding valley, which was carved by the namesake river that flows towards neighboring Tibet, a road, not always passable, scrupulously traces the path of the watercourse. After a few more hours, we reached the village of Pangmo, home to some 35 households, where the bus dropped us off at the roadside entrance to Yangchen Chöling Nunnery—the oldest of four nunneries in the Spiti Valley and the adjacent Pin Valley—established just 40 years ago and belonging to the Gelugpa school of Tibetan Buddhism. The other nunneries are Sherab Chöling, also of the Gelugpa tradition, Tsechen Chöling, following the Sakya tradition, and Dechen Chöling, which belongs to the Nyingma school.

Traveling into the Pin Valley, we were fortunate to visit Jomoling, a community of 13 nuns who have built their residences beside the small village of Tailing. The nuns showed us photographs that revealed their commitment to their Buddhist practice, which is largely confined to the harsh winter months. In the summer, the nuns spend much of their day working the fields or helping to maintain the roads, leaving very little time for practice. Before the nunneries were built, the nuns either remained in the villages with their families or braved the elements as hermits in the caves nestled in the mountains, where their Buddhist practice would be unimpeded by the rhythms of village life—especially in the Pin Valley, where the nuns all follow the Nyingma tradition.

One such renunciate is Tashi Tsomo who, at 97, is the oldest nun in the valley. She ordained some 30 years ago after her husband died and has since stayed in retreat near the village of Poh. Although now all but deaf and blind, she spends her days reciting mantras and prayers. Her simple presence projects an aura of wisdom, and we found a measure of peace in sharing time with her. We also had the opportunity to pay our compliments the man who visits from the nearby village to take care of her. In Himalayan communities, respect is clearly due and paid to the elderly—nobody asks them to renounce their lifestyle merely because they are getting old. It is a natural part of life to care for the older members of society, an observation that moved us greatly.

The recent establishment of nunneries in the Spiti Valley is a reflection of a movement to expand the reach of education within Tibetan Buddhist communities. With the support of associations such as the Tibetan Nuns Project and the Jamyang Foundation, female monastic communities such as those in the Spiti Valley have been able to open schools for the nuns, although finding instructors, especially in such poor and remote areas, has always been extremely difficult. As has been well documented, even in the Buddhist world women have faced considerable gender discrimination, especially in the area of education, and were traditionally undervalued in this largely patriarchal society. For example, it took a long time for the nuns of Yangchen Chöling to find a teacher willing to teach them.

Tseten, who became a nun in 1996 at the age of 13, recalls the day a kind monk who had been meditating in a cave near the valley agreed to teach at their nunnery. For several months, they all studied together happily until one day, to the great dismay of the nuns and their teacher, a group of monks from his home of Kee Monastery in the valley arrived and told him he could no longer teach at Yangchen Chöling. Committed to his new mission, the monk eventually left his monastery to continue teaching the nuns.

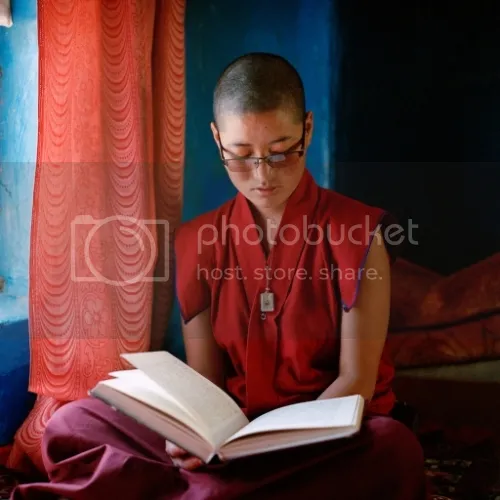

Yangchen Chöling later applied to become a branch campus of the Institute of Buddhist Studies in Leh, Ladakh. The branch school officially opened in 2011. Each summer since then, the nuns have organized a traditional debating contest in Spiti, with the host nunnery alternating each year between Yangchen Chöling and Sherab Chöling. During the 10-day event, some 75 nuns debate and exercise their intellectual skills under the encouraging and sympathetic eye of their philosophy teacher.

Education is so clearly the key to the emancipation of women. Hasn’t His Holiness the Dalai Lama himself been encouraging nuns to study Buddhist philosophy for more than 40 years? For the nuns themselves, the stakes are high: as Doctors of Philosophy called Geshema, they will be called upon to teach—a role previously reserved for monks. We strongly hope that some of these deeply committed nuns of the Spiti Valley will one day graduate as Geshema.

Steps have been taken to improve the situation. Another two structures for schooling and accommodation were erected at Dechen Chöling and Tsechen Chöling in summer 2015; yet more buildings are needed to accommodate new young nuns. The schools attached to these nunneries opened two years ago, and both are seeking sponsors to fund day-to-day operations.

Lama Pema Samdup, initially assigned to the Sakya monastery in Kaza, the main township in the valley, has since dedicated himself to the nuns’ cause. In 2006 he set up the Sapan Foundation to promote Buddhist culture in the Spiti Valley and in particular to help the nuns. His actions are now beginning to bear fruit with the support of humanitarian organizations from the Czech Republic and France that have been won over by his sheer enthusiasm and generosity in serving these women.

When we left Spiti, it was with a warm feeling of pride on behalf of the nuns. Our hearts had been filled to overflowing by their generosity, their compassion, and their extraordinary motivation. We feel quite sure that, with their determination to work for the benefit of all beings, the nuns will contribute greatly to life in the valley and that they are well prepared for the challenging road ahead.

Olivier Adam is a member of Dharma Eye–The Buddhist Photographer collective. To learn more about Dharma Eye and Olivier’s work as a photographer, visit Dharma Eye.

See more