The Wheel of Life and Death is a central concept and image in Buddhist understanding. Escaping the Wheel of Life and Death is a Buddhist aspiration. Being unable to escape the Wheel of Life and Death would be a condition of spiritual torment. Yet, this is where the protagonists of many Japanese Noh plays find themselves: as ghosts unable to escape the Wheel of Life and Death.

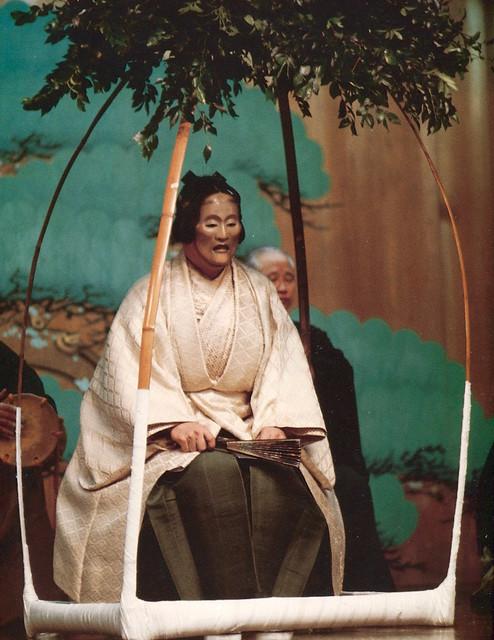

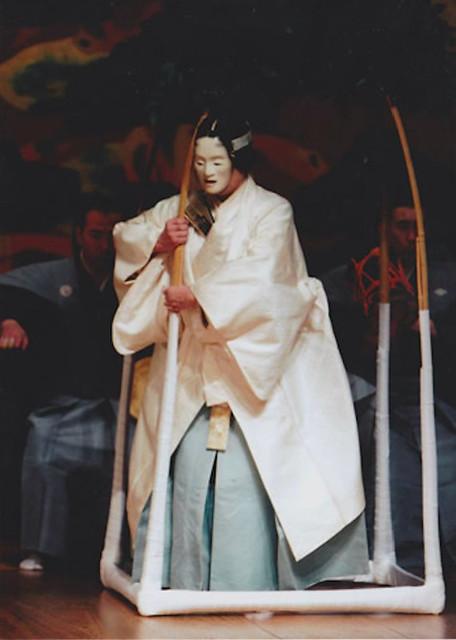

character Unai in Motomezuka, Act 2, mask carver unknown.

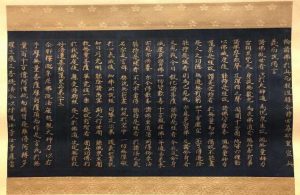

Circa 19th century, wood. After Toru Nakanishi and Kionori

Komma, Noh Masks, Color Books, Tokyo, 1960

Japanese Noh Theater is magnificent and rarefied—a living Buddhist performance art more than 700 years old with roots and formal elements much older. In the 14th century, the performer-playwright and head of a performing clan family Kan’ami Kiyotsugu (1333–84) wrote the play Motomezuka (“The Sought-for Grave”), which tells the plight of a maiden who committed suicide after two young men killed each other when fighting over her. Kan’ami’s son, Zeami Motokiyo (c. 1363–c. 1443), further refined both the artistic and spiritual qualities of the play—the Beauty and the Sadness.

Aesthetic moments in Noh plays—such as those produced by a subtle manipulation of the mask—are Zen moments revealing “the suchness of things,” but the story is couched in Mahayana terms of redemption and progress on, or escape from the Wheel of Life and Death, to a better rebirth or to enlightenment. The poetry of the art form relies on the misdeeds and spiritual mishaps of the main characters, who are often great figures from pre-Buddhist Japanese history, now made over into stories of their afterlives.

Circa 1900, woodblock print. From Core of Culture

Noh is art, not religion. It speaks with the combined languages of dance, song, chant, music, poetry, and drama. Ghosts return to re-live the love, or battle, or karmic experience binding them to traverse the hells in restless spiritual anguish. They pretend to be real people, but often a wandering priest will discover their ghostly identity and can therefore pray and release them from the Wheel of Life and Death. Not so for Unai, the maiden in Motomezuka.

Toshiro. After Shinjinbutsu Orai, Inc., Noh Photographs, 1987, pl. 62

On one level, Noh plays are morality plays. They are exercises in artistic Zen. A variety of spiritual states are the content for artistic choices in Noh, using the Wheel of Life and Death as a canvas and palette for tragedy, love, ecstasy, and the journey through different realms. Noh plays are seasonal, and meant to be performed at specific times of year. Motomezuka is a play to be performed in late winter/early spring: an analogy for a winter that never ends.

Please enjoy the following excerpts from a performance adaptation of Donald Keene’s translation of Motomezuka (Keene 1970, 42–44). Noh plays embody the truth of the evanescence of life and being. The energy of the actor pours through the mask and costumes. The scene here, which occurs in Act 1, is the maiden Unai’s response to the traveling priest when he asks her what she is doing. In the second half of the play, to follow, Unai reveals that she is a ghost unable to escape the Nine Hells.

Image courtesy of the estate of Karen Brazell, copyright Global Performing

Arts Database

From Motomezuka:

We pluck spring greens in Little Field at Ikuta

A sight so charming we delay the travelers who stop to watch

Such foolishness, foolishness, all these questions!

Guardians of the watchfires on Kasuga Moor

Come out and look

Guardians of the watchfires

Come out and see

So little time remains before the tender herbs are plucked and

So little time remains for you too, oh traveler.

So few days before you see the capital you hurry to

For your sake I went out into the fields of Spring

To pluck the tender shoots

To pluck the tender shoots

My sleeves are cold

The snow lies iced

But we shall gather herbs

coated though they be with sleet

We shall gather herbs

In the marsh the ice is thin

But it lingers on.

Reach down!

Pull up the watercress

By the long roots!

From the blue-green waters

Pull up the blue-green plant.

Though they may be few in kind

And they may be hard to find

A poet came to Spring Field to pick violets, so he said,

But he picked instead the plant they call “Young Purple!”

Purple is known as the color of affinity

A bridge that joins lover and beloved.

But now . . .

That bridge is broken.

Spring is here but this morning looking at snowy fields

It feels like the old year still.

The Spring is cold and barren

The morning wind bleak across the fields,

While in the forest

The lower branches of the pines

Bow with the burden of the snow.

And where is the Spring, we wonder?

Where is the Spring?

1977. Photograph courtesy of the estate of Karen Brazell, copyright

Global Performing Arts Database

References

Keene, Donald. 1970. 20 Plays of the Noh Theater. New York: Columbia University Press.