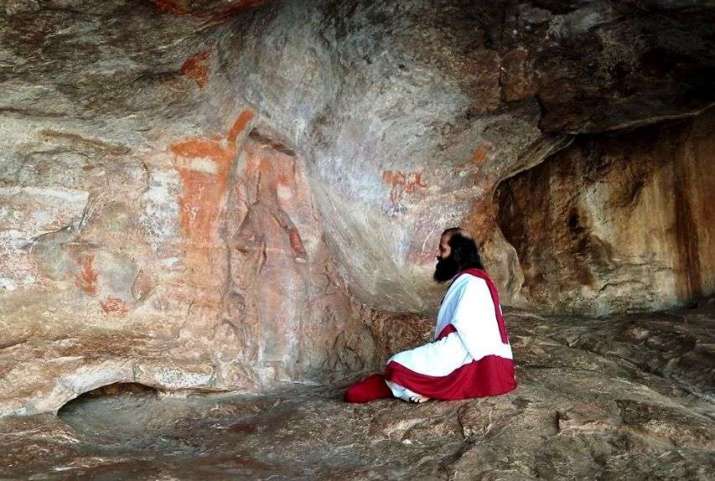

Image courtesy of Prabodha Jnana and Abhaya Devi

Prabodha Jnana and Abhaya Devi are an Indian Buddhist couple living in Bangalore and trained under the guidance of eminent masters of the Nyingma tradition of Vajrayana Buddhism. Prabodha Jnana is a Buddhist yogi, meditation teacher, philosopher, and writer who gives discourses based on the wisdom teachings of the Buddha in a format suitable for the modern context. Abhaya Devi is a Buddhist yogini, meditation teacher, writer, and artist. The couple divide their time between retreats, guiding others in Dharma practice and exploring the history of Buddhism in India. In 2008, under the guidance of Kyabje Penor Rinpoche,* they established a Dharma center for the Palyul Nyingma tradition in Bangalore. In 2016, they launched the Way of Bodhi website to make the teachings of the Buddha accessible to a broader audience.

In this, the second part of our interview, Prabodha and Abhaya discuss the genesis, development, and decline of Mahayana Buddhism in South India, and some of the discoveries of their unique research.

Buddhistdoor Global: What is the role of South India in the genesis and development of Mahayana Buddhism?

Abhaya Devi: It is a not-so-well-known fact that South India played a pivotal role in the genesis and development of Mahayana. In fact, the Prajnaparamita Sutras proclaim that those sutras originated in South India.** Furthermore, Mahayana, as a distinct movement, started with Acharya Nagarjuna from the south. In the trail blazed by Nagarjuna, many great scholars came up from the south and went on to become the charioteers and ornaments of the Nalanda tradition. These include Buddhapalita, Bhavaviveka, Dharmapala, Chandrakirti, Dignaga, and Dharmakirti.

The propagation of Buddhism to China and the rest of East Asia was mainly from South India, enriched by its maritime ties and links. As you might be aware, the Chan (Zen) tradition of Buddhism traces its origin to Bodhidharma from Kanchi in present-day Tamil Nadu. Japanese Shingon Buddhism traces its roots to the Yoga Tantra teachings of Vajrabodhi from present-day Kerala.

The Gandavyuha Sutra (part of the Avatamsaka Sutra)has a fascinating narrative about the voyage of Sudhanakumara from Dhanyakataka (in Andhra Pradesh) in search of enlightenment. He meets the bodhisattva Manjushri, and upon his instructions travels to Mount Potalaka in the deep south to receive teachings from Avalokiteshvara. Based on Xuanzang’s records, the Japanese scholar Shu Hikosaka mapped Potalaka to the present-day Pothigai Hills (Agasthyakoodam) in the deep forest between Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

South India was also home to many Mahasiddhas of Vajrayana, including Shavaripa (Sabareesha) and Padampa Sangye (Paramabuddha). Sriparvata (Nagarjunakonda to Srisailam) and Malayagiri (the southern part of the Western Ghats) were prominent centers of Siddha’s congregation.

BDG: What are the similarities and differences in the development of Mahayana Buddhism in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Kerala?

Prabodha Jnana: On the Deccan Plateau of Karnataka, Buddhism had an early start and an early demise. Being a part of the Ashokan empire, Buddhism flourished there from its early stages. Despite the early decline, this region abounds with glorious Buddhist remains, even now. These include stupas and edicts from the Ashokan era, cave temples with the carvings of buddhas and bodhisattvas, remains of viharas (monasteries), statues of bodhisattvas, and so on.

In contrast to the plateau, in coastal areas and the mountainous Malenadu region of Karnataka, Mahayana and Vajrayana flourished until the 12th century. The kings there enforced Chatusamaya, which meant that the four observances—Buddhism, Jainism, Saivism, and Vaishnavism—had to co-exist with mutual respect and without criticizing each other. From one perspective, this allowed the peaceful co-existence of all schools, but from another perspective, it became a muted existence. Rational and critical examination suffered under this model. Some compromises on the Buddhist rejection of the caste system would have taken place to fit into such a co-existence.

In Kerala and Tamil Nadu, all forms of Buddhism lasted until 12th and 14th centuries, respectively. In some pockets, such as Nagapattinam, Buddhism was active until the 17th century. An open culture thrived in Kerala and Tamil Nadu, giving rise to many world-renowned scholars and many unique Buddhist traditions. Vajrayana was secretly practiced here until the 17th century. Buddhaguptanatha, the guru of the 17th century Tibetan Buddhist master Taranatha, was from Rameshwaram in Tamil Nadu. According to Taranatha, Guru Padmasambhava also taught in Tamil Nadu. Interestingly, we came across an ancient Buddha statue in Tamil Nadu that resembles Guru Rinpoche.

Despite the long-term survival of Buddhism, there are very few structural remains of Buddhism in Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Nevertheless, we can spot plenty of ancient statues of buddhas and bodhisattvas abandoned in those regions.

Guru Padmasambhava. Image courtesy of Prabodha Jnana and Abhaya Devi

BDG: What is the most important discovery in your research in the region?

AD: There are some popular myths about the decline of Buddhism in Kerala and Tamil Nadu that keep people away from Buddhism. The myth in Kerala is that the Vedanta philosopher Adi Shankara*** defeated Buddhists in debate and with that Buddhism disappeared from Kerala. A similar myth exists in Tamil Nadu in the name of Thirugnana Sambandar.**** Due to these myths, many people here have a misinformed notion that Buddhism is an inferior tradition that was invalidated long ago.

In sharp contrast to these myths, our studies indicate that Buddhism flourished in this region until at least the 12th–14th centuries. Buddha statues found in Kerala and Tamil Nadu date to periods much before and after Shankara and Sambandar. The later viharas of Kerala and Tamil Nadu find mention even in faraway places such as Nepal and Korea. So it is clear that Buddhism did not suffer a decline due to either Shankara or Sambandar. Rather, but continued to flourish for many more centuries. Also, when we researched the texts of Shankara and Sambandar, it became clear to us that their debates with Buddhism were with fictitious opponents. If there were any real debates, anyone with even a basic knowledge of Buddhism could have refuted them.

Image courtesy of Prabodha Jnana and Abhaya Devi

BDG: How, then, did Buddhism come to decline in Kerala and Tamil Nadu?

PJ: The decline seems to have happened at a later time. In Kerala, the non-Buddhist priestly class, who became influential over the royalty, enforced a rigid caste hierarchy and untouchability. They could not tolerate the egalitarian approach of the Buddhists, who refused to fall in line. Thus the priestly class declared that the Buddhists were social outcasts. It then became challenging for someone to be openly Buddhist. Although outwardly Buddhism was suppressed, it remained in the hearts of the masses for much longer. Due to this, we can see strong Buddhist influences in the language, culture, art, and festivals of Kerala, while there are hardly any Buddhist structural remains.

In the case of Tamil Nadu, the rising popularity of devotional cults led to the gradual decline of Buddhism. The devotional cults ridiculed reason and offered simplistic solutions to the masses. As the support of kings and the masses shifted to mere devotion, self-effort based systems such as Buddhism lost popular support.

BDG: Prabodha Jnana and Abhaya Devi, thank you very much for your time!

District, in Tamil Nadu. Image courtesy of Prabodha Jnana and Abhaya Devi

* Kyabje Penor Rinpoche (1932–2009) was the 11th throneholder of the Palyul lineage of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism. He was the supreme head of the Nyingmapa lineage from 1993–2001.

**This is mentioned in the Prajnaparamita Sutras in lines 8,000, 18,000, and 25,000.

*** Adi Shankaracharya of Advaita Vedanta, who was born in Kerala in the eighth century.

**** Thirugnanasambandar was an influential Saivite saint of Tamil Nadu in the seventh century.

See more