We surround ourselves with the true image of ourselves.

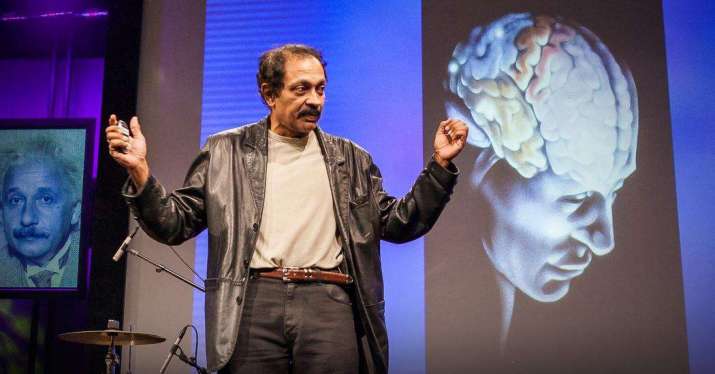

A quote attributed to Ralph Waldo Emerson that I chanced upon while reading The Age of Insight—a book that also draws on the work of neurologist and cognitive psychologist Vilayanur S. Ramachandran, whose insights have long fascinated me. The book intriguingly explores a synthesis of biology with deep psychology. And while it focuses on a particular time and place in European history, it remains a fascinating deep read on the mechanics of the brain in relation to the inner and outer worlds of self, society, and art, and certainly helped deepen my insight into the biology of the mind and sacred art.

The significance of our relationship with art is a profound one and its use within the world of the sacred is as old as campfires and storytelling. And it is a story worthy of deeper understanding. Why it is that dressing our walls with painted icons is more than a fashion statement, and why altars of faces staring back at us are more than something we meditate on.

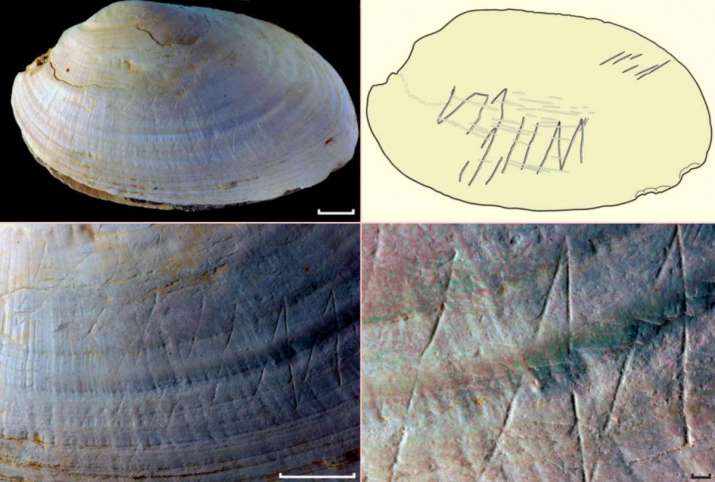

Geometric art, of sorts, has been found on shells in Indonesia, dated to some 500,000 years ago and implicating Homo erectus as budding artists. Then Homo sapien created similar zigzags on the walls of the Blombos caves of South Africa around 70,000 years ago. Geometric art evolved in many cultures around the world, in the form of knotwork found in Celtic, Viking, and Asian societies, through to Islamic Arabesque, beguiling us at first with hypnotic complexity, beauty, and often profound meditations. Our biology seeks out symmetry.

Neanderthals appear to have created abstract art in caves in Spain some 65,000 years ago, and the oldest figurative painting appears to be a depiction of a bull in a cave in Borneo circa 40,000–50,000 years ago by Homo sapiens. And between 25,000 and 40,000 years ago, the human hand was very much the subject of attention, until the end of the last ice age when it all abruptly stopped.

From we can deduce today from the information shared, some simply felt compelled to express themselves by their own hand. And we are now instinctively drawn into and moved by the essential simplicity and almost caricature nature of primitive oxen paintings that arguably captured the “rasa” of their subjects, a Sanskrit term I shall return to. The drive not only to beautify, but to share through images is hardwired into our collective psyche.

Some have suggested that it was the sharing of information as art that set the trajectory for the success of our species. We were able to inform others in ways that might not have been so apparent with other Hominidae. Maybe the artists in Borneo simply loved the animal they depicted. Perhaps it was an expression of offering to the spirit of the animal to keep humans in the oxen’s grace. Possibly they wanted to let others know that there were cattle in the region, which would have implied a supply of food and leather and a higher likelihood of staying alive.

While we may never know the motives, they potentially stand as an example of information sharing from an individual to the many. From one simplified visual expression, our brain has the ability to assimilate and practice the information almost instantly. It is an unquestioned advantage in our evolution. Neurologists tell us that this is, for the most part, thanks to mirror neurons—neurons that are biologically responsible for imitation, emulation, and the social skill of empathy and helping with our mental reality and projection. We also know that artistic evidence of shamanic activity was expressed ubiquitously around the globe, images of which are generally figurative and curious.

“The purpose of art is not realism . . . the purpose of art is hyperbole,” Ramachandran tells us. Artists often use the principal of metaphor, and our brain loves it. Our brain revels in the search to unearth a mystery, to the “a-ha!” moment when the final puzzle piece slots into place—the private, almost elitist satisfaction of understanding an artist’s symbolic language. When our brain finally sees the pattern, it climaxes for a fleeting moment as it elicits the meaning, exciting certain neurons and sending information to the limbic system, into the sympathetic nervous system that we then experience as an emotional response. A response the limbic system remembers.

Symbolism and figures in art are a “language” used by the artist, but it quickly became apparent that the human face, more than anything else, holds a special place in our psyche. Six regions of our brain—more brain usage than for anything else—directly relate to our prefrontal cortex and are solely allocated for facial recognition. The faces of deities tap into this primitive program, prompting a need for information and guidance. But our brain doesn’t really care much for unnecessary effort, and given that it can only direct its full attention to one thing at a time, it wants to jump straight to the essential information. This information works on the Gestalt principle of top-down processing and closure, which is to say that we mentally prefer to close visual gaps. Our brain is hyper-excited by the exaggeration of isolated line stimuli of critical information, a situation referred to as “peak shift.”

It is Ramachandran again who discusses the term “rasa” in relation to art. The Sanskrit term rasa struggles to find a direct translation in English: it is the soul of a thing, its beingness, its essence, but the “essence of something to invoke optimal neurological titillation” as Ramachandran puts it. A titillation that our limbic system loves. When we are moved by the inherent rasa of spiritual art, it arguably permeates our very biology, our inner emotional primitive, and thanks to our mirror neurons we experience qualia, fully aware of the sensations we are experiencing. Unconsciously and consciously we can be impacted in profound ways.

Deity art, especially as expressed in meditational roadmaps such as thangkas, also tend to be presented in a timeless, but ever-now way. In the same way, the sumi-e paintings of Japan express shadow in images that would otherwise be placed in a linear concept of time. They typically rely on metaphor, exaggeration, often full of pattern and detail, yet simple and full of . . . rasa.

“We surround ourselves with the true image of ourselves” as deities are exaggerated reflections and reminders of aspects of our inherent nature; a visual lamrim* as we walk the path of opening each facet of our being and potential, as well as being equivalent to the adage “we become the company we keep” and the paintings become our sages.

Proust said of art that it is “a mechanism that can restore beauty and interest to things that have been unfairly neglected.” These things are not always physical.

So with thanks to our mirror neurons and the theater of our mind where we run virtual simulations, meditating on deity art has the biological potential to facilitate our own personal apotheosis.

* A Tibetan Buddhist textual form for presenting the stages in the path to enlightenment.

With thanks to the work of Vilayanur S Ramachandran MD; Eric R. Kandel; Genevieve von Petzinger, paleoanthropologist and cave art researcher; Leonard Shlain; Ralph Waldo Emerson; and Proust, as well as all of the countless researchers of the mind and ancient art.

References

Kandel, Eric. 2012. The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain, from Vienna 1900 to the Present. New York: Random House.