Having previously established the context of Vajrayana in relation to the general Buddhist teachings and Buddha nature as the premise of its path,* this third instalment in our four-part series looks further at the logic of Vajrayana view and practice.

Empowerment

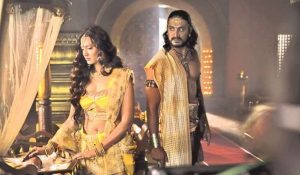

With a foundation of renunciation, compassion, and devotion, the qualified Vajrayana student is given four empowerments to take possession of an innate heritage of abiding purity, and is thus anointed as heir to the kingdom of enlightenment. In ancient times, this involved the guru actually performing an elaborate enthronement ceremony for the student, but regardless whether they are given with such formality or not, receiving these four empowerments is a defining moment for the practitioner as it marks the entrance into Vajrayana. From then on, he or she commits to the samaya discipline of upholding and integrating this sacred vision through the practice of sadhana—the methods to accomplish the Vajrayana path.

Proximity to the goal

It is essential to recognize that the objective of the Mantra Vajrayana path is consistent with the objective of the gradual Sutra path, namely the removal of obscurations and the realization of wisdom. Yet, through the foundations of purification, accumulation, and mingling with the teacher’s wisdom, the Vajrayana yogi has a greater proximity to enlightenment in terms of confidence in their subjective experience. The great 19th century scholar Yönten Gyamtso writes:

“The object of valid cognition of the view in both Sutra and Mantra is established as freedom from conceptual constructions, and as such there is no difference. However, in regards to the manner of the subject that sees this, there is a difference: it is through the subject that the view necessarily is engaged, and hence such a difference is enormous.” (Yönten Gyamtso 1987, 78)

The Vajrayana student has been processed with the establishment of the foundational practices and has acquired insight into the view of the bodhisattvas, namely equanimity of meditation united with the post-meditation knowledge that sees relative appearances as inseparable from the space of reality. Transformation of the subject also provides a very different view on the two truths, known therefore as the superior two truths, which is basic to the Vajrayana practice of pure perception, or sacred outlook. This valid cognition of purity lies at the core of the practices of the four empowerments, and is particularly the focus of the first empowerment with its development stage practice of visualization, mantra recitation, and samadhi.

Purity and equanimity: the superior two truths

The superior two truths consist of understanding absolute truth as the equanimity of freedom from conceptual constructs and relative truth as the purity of perceptions—such that all apparent phenomena are seen in terms of wisdom, as a mandala of infinite purity.

This proposition is not unique to Vajrayana. In the Prajnaparamita sutras, we find in the Vimalakirti Nirdesha Sutra the Buddha teaching Shariputra about the innate purity of the world. While Shariputra sees the world as a place of suffering, the Buddha points out that this is his own perception:

“Sariputra, it is through the transgressions of sentient beings that they do not see the purity of the Tathagata’s (i. e., my) buddha land. This is not the Tathagata’s fault! Sariputra, this land of mine is pure, but you do not see it.” (McRae 2004, 78)

The Vajrayana view of pure perception is integrated in meditation through the development stage practice of visualizing deity and mandala. As the late Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche (1920–96) points out, and consistent with the above quotation, this is not imagination but assessing things as they are intrinsically:

“Development stage is not like imagining a piece of wood to be gold. No matter how long you imagine that wood is gold, it never truly becomes gold. Rather, it’s like regarding gold as gold: acknowledging or seeing things as they actually are.” (Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche 1999, 71)

In his Overview, Jamgön Mipam Rinpoche (1846–1912) writes on pure perception of appearances:

“. . . appearances are established in the mode of reality as the mandala of the exalted body and wisdom because the Sublime Ones free from distorting pollutants see [appearances] as pure; like someone with unimpaired vision seeing a conch as white.” (Duckworth 2008, 128)

The Vajrayana yogi might not be a realized or sublime person, yet having been processed through the foundation practices described earlier, he or she trains in recognizing reality as it is, free from obscurations—just as someone who has jaundice recognizes that despite their own impure perception of seeing a conch as yellow, it is, in fact, white. Realization of this view is effectively accomplished through the practices of the four empowerments.

Purification, perfection, and maturation

The methods of the four empowerments purify increasingly subtle habitual perceptions of samsara and unveil the spontaneously present perfection of nirvana, with each empowerment maturing the qualities prerequisite for the practices of the next empowerment. For example, the development stage meditation of the first empowerment of visualizing the world as a mandala purifies impure projections, establishes the spontaneously perfect unity of appearance and emptiness, and matures the yogi for the second empowerment, the completion stage meditation that in turn purifies the physical body as a mandala. Explaining purification, perfection, and maturation as they pertain to the first empowerment, the great sage Dza Patrul Rinpoche (1808–87) writes:

“Since it parallels the features of samsara, existence is purified and refined away. Since it parallels the way nirvana is, the result is perfected in the ground. And finally, both of these mature one for the completion stage.” (Jigme Lingpa et al. 2008, 29)

The path of the four empowerments purifies the habitual patterns related to our ordinary perceptions, unveiling the innate purity of all phenomena as wisdom display. The pinnacle practices of the four empowerments are the practices known as Mahamudra and Mahasandhi, which take innate wisdom itself as the path.

Samaya

It is said that the life force of the Vajrayana empowerment is keeping the sacred discipline of samaya. As with any of the Buddhist vehicles, discipline is the lifestyle reflecting the view. Vajrayana samaya discipline reflects the Vajrayana view but is also founded on the pratimoksha vows of monastic discipline, as well as the bodhisattva discipline. The practice of uniting these three levels of vows is intrinsic to Tibetan Buddhism. Thus, you could be a monk, upholding the Vinaya, bodhisattva, and Vajrayana disciplines all united without conflict. Such a person would be known as a Three-fold Vajra Holder. One supreme example is the late Kyabje Trülshik Rinpoche (1923–2011), a teacher of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who in addition to being a great Vajrayana and Mahasandhi master was also a principal holder of the Vinaya lineage and regarded as a great bodhisattva.

While the Vajrayana discipline is not easily maintained, it can be repaired. The great Indian master Atisha Dīpamkara (980–1054) once commented that while his pratimoksha precepts were intact, his bodhisattva vows occasionally needed repairing. However, he claimed, his infringements of the Vajrayana samayas would fall like rain! Hence the practitioner of sadhana makes sure to continually purify and amend the samaya vows.

Fruition

Through the Vajrayana path, the temporary delusion of samsara can be swiftly brought to an end, the qualities of enlightenment become fully manifest, and the spontaneous benefitting of others consequently bursts forth pervasively and constantly. Vajrayana is often referred to as the swift path to enlightenment, and the tantric scriptures speak of enlightenment within sixteen, seven, or three lifetimes, or even just one. This is due to the degree to which the practitioner has a clear experience of wisdom, as discussed above in terms of greater proximity, and also through skillfully integrating relative truth as inseparable from the wisdom of ultimate reality.

In the lineages of Indo-Tibetan Vajrayana there are countless persons who have displayed the attainment of enlightenment, benefitting others and their societies at large and providing guidance both in securing temporal happiness and on the path to complete liberation. These lineages reach us today, and the teachings on Vajrayana view and practice remain intact.

The final instalment will consider how the Vajrayana path is transmitted and practiced in the modern world.

References

Duckworth, Douglas. 2008. Mipam on Buddha Nature. Albany: State University of New York Press (SUNY).

Jigme Lingpa, Patrul Rinpoche, and Getse Mahapandita. 2006. Deity, Mantra, and Wisdom. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications.

McRae, John R. 2004. The Vimalakirti Sutra (PDF). Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research.

Price, A. F., and Wong Mou-lam. 1969. The Diamond Sutra and the Sutra of Hui Neng. Boston, Shambhala.

Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche. 1999. As It Is. Hong Kong: Rangjung Yeshe Publications.

Yönten Gyamtso. 1987. yon tan rin po che’i mdzod kyi ‘grel pa zab don snang byed nyi ma’i od zer from rnying ma bka’ ma rgyas pa, vol. 39. Darjeeling: Dupjung Lama. Translation by the author.

*See:

Approaching Vajrayana

Approaching Vajrayana – Part Two: Ground Tantra and Blessing

Jakob Leschly is Resident Teacher for Siddhartha’s Intent Australia. He is a student of the late Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, as well as Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche.