Dr. Amy Heller, an assistant lecturer at the Institute for the Science of Religion and Central Asian Studies, University of Bern, delivered two online lectures on Tibetan Buddhist art in March, organized by the Centre of Buddhist Studies at the University of Hong Kong. Dr. Heller is a Tibetologist and art historian specializing in Tibetan art and architecture. Her publications explore Tibetan art, Tibetan Buddhist art, early Himalayan art, Tibetan manuscript paintings, and sculptures. She also takes part in projects to restore the architecture of Tibetan monasteries, curate exhibitions of Tibetan visual art, and conduct research into Tibetan manuscripts.

In her first lecture, Dr. Heller provided an introduction to Tibetan art and archaeology during the 7th–21st centuries. She explained that the development of Tibetan art and archaeology can be divided into six distinct periods. The first period covers the 7th–9th centuries, when tomb artifacts and early Buddhist art were dominant in eastern and central Tibet. The earliest Tibetan archaeological artifacts are non-Buddhist and include items such as gold plaques depicting royal hunters and hunting themes. Similarly, the earliest Tibetan paintings are non-Buddhist with local themes, such as imagery related to the 12-year calendar cycle. These are depicted on wooden coffins excavated from aristocratic tombs in Qinghai along the Silk Road. With the expansion of the Tibetan Empire and cultural exchange along the Silk Road, Buddhism was disseminated to Tibet. Murals with Tibetan royal portraits and Buddhist themes—such as Vairocana Buddha with attendant bodhisattvas as mandalas—appeared in the Dunhuang and Anxi Yulin Grottoes when these regions along the Silk Road were under Tibetan control in the late eighth to mid-ninth centuries. Portable paintings such as the Medicine Buddha and drawings on paper of mandalas of Vairocana were also prevalent.

The second period defined by Dr. Heller was during the 10th–14th centuries, when Buddhism was widespread on the Tibetan Plateau. Buddhist art in western Tibet was influenced by the Kashmiri aesthetic style, while art in central Tibet was inspired by Indian and Nepalese styles. The prosperity of Buddhism facilitated the reception and adaptation of multiple aesthetic stimuli. The development of Buddhist art in Western Tibet will be expanded upon in our discussion of the second lecture below. In central Tibet, the majority of artists were Tibetan and Nepalese painters working in the Indo-Nepalese style. Indian Buddhist panditas such as Atisha (982–1055) traveled from the great monastic universities of Vikramashila to Tibet, bringing Buddhist manuscripts as didactic tools for teaching their Tibetan students—thus, the illuminations in such manuscripts brought the “rgya gar lugs” (Indian style) paintings to central Tibet. The collaboration between Tibetan and Nepalese artists resulted in aesthetic fusions. For example, an interesting painting in Grathang Monastery (late 11th century) presents the Buddha and a bodhisattva painted in the Indian style for the facial shape and usnisha,* but wearing Tibetan robes. Besides, Chinese features such as a clasp on the robe of the Buddha image are shown (Fig. 1). In China’s Central Plain, Tibetan monks, who were prelates for certain rulers during the Xi Xia period (1038–1227) and the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), brought Nepalese and Tibetan artists to the royal courts. One renowned Nepalese artist, Araniko, served the Yuan court in the 13th century. The works of these artists are in the spirit of the artistic fusion of the Nepalese style and casting techniques adapted to the imperial taste of the Yuan dynasty. The artifacts of Araniko and his disciples convey new compositions to the development of Buddhist art in the Central Plain region.

Late 11th century. Photo by Amy Heller, 1995

The third period was during the 15th–16th centuries. The Yongle Emperor (r. 1402–24) of the Ming dynasty was a zealous Buddhist and supported the production of a large number of sculptures, embroideries, and Buddhist manuscripts for practice in his court and as gifts for Tibetan monks. Artworks during this period show mixed Chinese, Nepalese, and Tibetan aesthetic styles. Influenced by the Yongle court and Newar art of Nepal, Gyantse in central Tibet became the leading center for Tibetan Buddhist art in the early 15th century. Many of these paintings were signed by the artists. Kumbum Gyantse Monastery, an architectural mandala, is a representative with an integral complex of sculptures and murals.

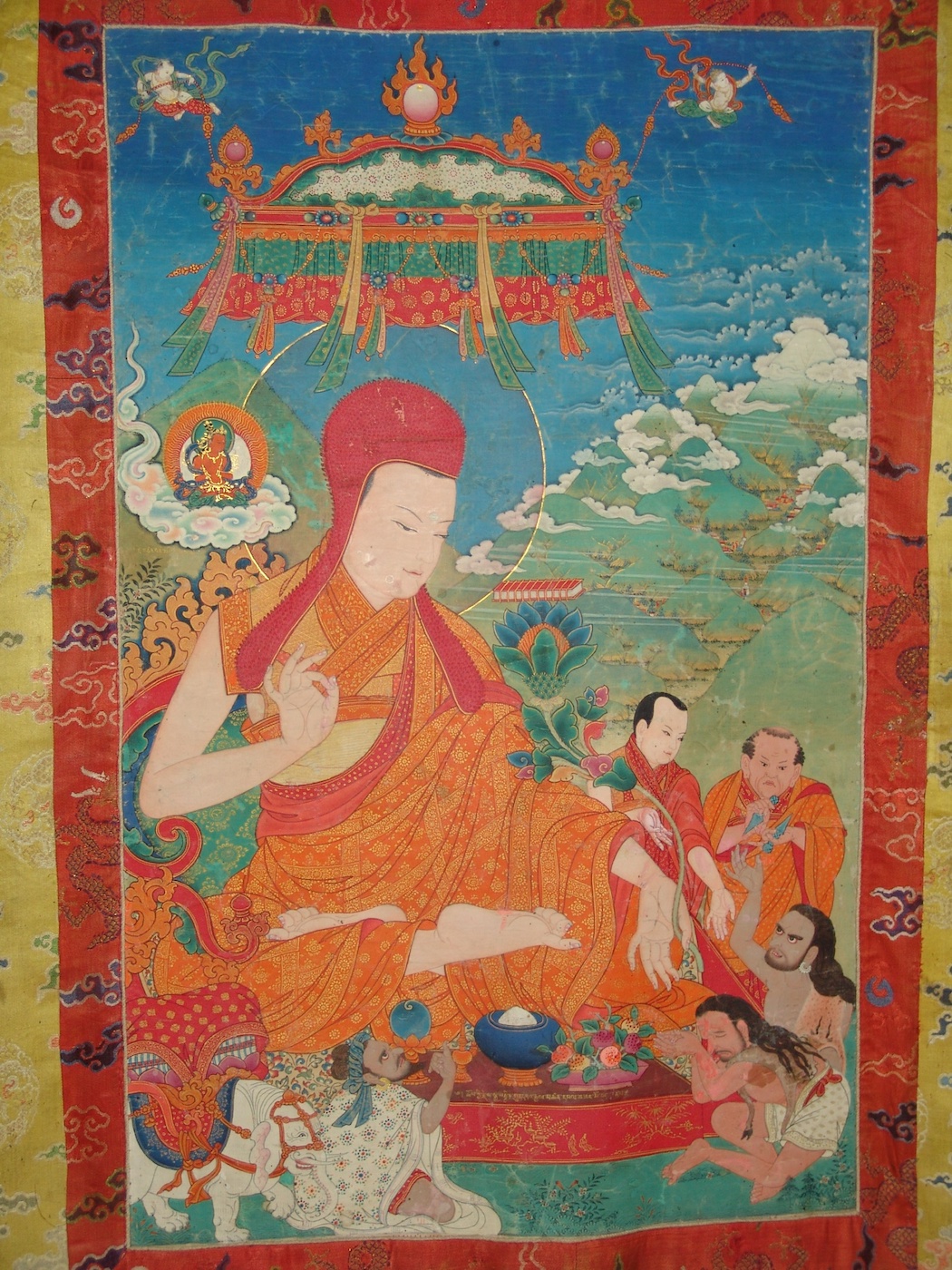

In the fourth period, Tibetan art in Gyantse and Lhasa in central Tibet and portions of eastern Tibet developed gradually through the 16th–17th centuries. Several early Tibetan art schools were established with their own individual styles. Paintings of the Khyenri school feature delicately painted facial expressions of the principal subject and his entourage in a divine landscape of blue skies and green hills (Fig. 2). During this period, the rise of the Gelugpa monastic order promoted aesthetic uniformity because of the wide diffusion of paintings based on woodblock stencils, thus promoting the growth of the New Menri painting school, such as the portrait of the Fifth Dalai Lama, which includes the buildings of the Potala palace in his portrait. The Gadri style developed independently in eastern Tibet, with compositions of vast landscapes often depicted with pale ethereal light and haloes surrounding portraits of the Buddha and disciples.

50 x 80 centimeters. Gongkar Monastery. Photo by Penba Wangdu

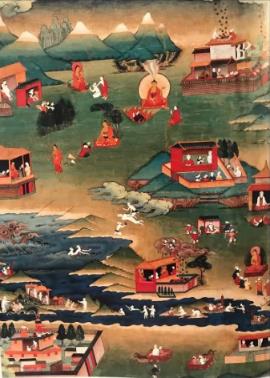

During the fifth period in the 17th–19th centuries, master artists such as Chos Dbyings Rdo Rje (1604–74) and Situ Panchen (1700–74) were influenced by Chinese painting styles in developing their own personal styles. Reflections of the Chinese style of depicting landscapes prevail. Fig. 3 is an example of an episode from the 108 stories in the Bodhisattva Avadanakalpalata, a collection of tales of the previous lives of the historical Buddha. The 20th–21st centuries marked the sixth period. Gendun Chopel (1903–51) and Amdo Jampa (1916–2002) were key artists who specialized in realism. Their paintings contain innovative styles mixed with Western modern art. In sum, the dissemination of Buddhism and cultural exchanges on the Tibetan Plateau have continually infused new elements into the development of Tibetan Buddhist art, leaving us magnificent artworks blending various cultures.

Avadanakalpalata, c. 18th–19th century.

78 x 55cm, Newark Museum

In her second lecture, Dr. Heller charted the Buddhist art of Western Tibet and the Western Himalayas in the 11th century. After a civil war in Tibet during the middle of the ninth century, the descendants of the Tibetan royal house migrated from Lhasa to western Tibet and established the Kingdom of Guge. Ye shes ‘od (959–1036), who was both the second king of Guge and a monk, endeavored to revive Buddhism by bringing original Buddhist scriptures and art to the kingdom. He invited a large number of panditas and artists from Kashmir and central India to translate Buddhist texts and embellish the sanctuaries. He also commanded royal support to build four monasteries in Tholing, Nyar ma, Khojarnath, and Tabo. The support of the royal family attracted a large number of Buddhist teachers and artists to settle in Guge. Being the first capital of Guge, Tholing became the new centre of Buddhist activity in the late 10th century.

Rinchen Zangpo (958–1055), the chaplain-translator, brought Kashmiri artists on his return from a mission to Kashmir and northeastern India. He also imported sculptures of different aspects of Tara, Avalokiteshvara and Manjushri from Kashmir. As a memorial for his father, he commissioned a life-sized sculpture of Avalokiteshvara by the Kashmiri sculptor Bhidhaka. This sculpture remains enshrined in Go Khar chapel at Khatse (Fig. 4). This Kashmiri-style Avalokiteshvara inspired imitation in similar sculptures in later periods.

Bhidhaka. Photo by Thomas J. Pritzker, 1999

Apart from Kashmir, the artistic styles of other regions also take their place in the development of Buddhist art in Guge. Murals in the ruins of Tholing, Khojarnath, and Tabo show coeval fusions of different artistic styles from Tibet, Nepal, and India. For example, the image of a female deity in the entry chapel of Tabo shows the application of Kohl, an Indian-style eyeliner (Fig. 5). Furthermore, certain images demonstrate possible foreign influences, such as winged lions. This might reflect cultural exchanges from trade along the Silk Road passing through western Tibet and the western Himalayas.

painting detail. Height c. 40 centimeters.

Photo by Amy Heller, 2008

Rinchen Zangpo’s collaborations with Kashmiri panditas such as Sraddhakavarman and Viryabhadra, as well as the Bengali pandita Atisha, led to many translations and re-translations of earlier texts. This had a profound impact on the liturgies represented in those temples and sanctuaries in Guge, with a particular emphasis on mandalas devoted to Vairocana. For example, Rinchen Zangpo’s work on the Sarva-Tathagata-Tattva-Samgraha and his re-translation of Manjushri-Nama-Samgiti, an exemplar of such texts, was found at Khojarnath, which concludes with the Dharmadhatu-Vagisvara mandala, as well as the text of the Sarvadurgatiparisodhana. In her lecture, Dr. Heller showed examples of the deities of those mandalas in Tholing, Tabo, Mangnang Monastery, and in the small cave temple of Nyag Lha Khang Dkar Po, near Tholing, rediscovered in 2007 by Thomas J. Pritzker and a team from Centre for Tibetan Studies, Sichuan University, directed by Prof. Huo Wei. In light of Tibetan dedication inscriptions and Tibetan historical documents, this presentation complemented the in-situ murals and sculptures by concentrating on a small corpus of Buddhist icons whose firm dates and distinctive iconography characterize artistic commissions in the context of Tholing, the royal monastery of the capital of the Guge kingdom.

As per Dr. Heller, the mixing of foreign influences in Tibetan art throughout history has resulted in “an aesthetically harmonious distinctive fusion.” However, our knowledge of Tibetan art is still fragmentary. The study of this subject is mainly based on the historic progression emphasis on regional schools. Some gaps represent potential data that we do not yet know. Therefore, we shall remain open to new data and information that might lead us to rewrite or discard previous hypotheses.

* One of the 32 major marks of the Buddha; a round or oval protuberance on the top of the Buddha’s head.

Wendy Yu Sau Ling is an amateur bird artist and is pursuing her PhD at the Centre of Buddhist Studies at the University of Hong Kong. Wendy’s research interest is in Buddhist art and she is currently studying bird images in the Chinese Buddhist grottoes.

See more