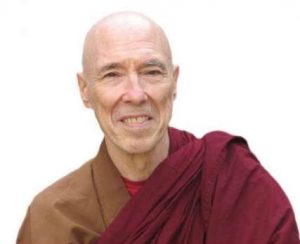

Many years ago, I took refuge in the three treasures for the first time under the late Ven. Rong Ling (融靈老和尚). While I remain a Mahayana Buddhist, a Pure Land Buddhist, over the years I have been drawn to the mysteries and profundity of Early Buddhism—that is, truly ancient Buddhism, pre-sectarian Buddhism, which transcends the Vehicles. As Ven. Rong Ling told me long ago, we take refuge under the Buddha before any preceptor or lineage. His passing in 2022 gave me further impetus to take refuge under another teacher, one whose spiritual and academic expertise covers both the Theravada and Mahayana, transcending sectarian boundaries. This teacher, whom I began following last year, is Prof. Ven. K. L. Dhammajoti, one of the foremost scholars on the Sarvastivada Abhidharma.

Even before taking refuge under him as a religion journalist, I had followed and covered Ven. Dhammajoti for years, certainly since 2015 when he launched the Buddha-Dharma Centre of Hong Kong (BDCHK). Before this, Ven. Dhammajoti already had an illustrious career. He had previously been awarded significant posts and honors: Chair Professor, School of Philosophy (Renmin University of China); Retired Glorious Sun (Endowed) Professorship in Buddhist Studies, (HKU); Rector and Honorary Rector (International Buddhist College Hat Yai, Thailand; presently, Rector Emeritus); and Adjunct Professor (University of Pune, India). He was also the founding editor of the Journal of Buddhist Studies, published annually by the Sri Lankan Centre for Buddhist Studies.

“Importantly, being a non-sectarian Buddhist does not mean obliterating the different Buddhist sects and traditions. Nor does it mean to relinquish the tradition that one happens to belong to. Nor does it mean to deny one’s inner love, faith, and respect to it. It does mean transcending sectarian biases and return to the True Dharma of the Buddha himself—not institutionalized ‘Buddhism,’” he told me in October.

“The True Dharma—not the tradition per se, however much love we have for it—must be upheld as our ultimate refuge and reliance (pratisharana). We must necessarily learn from the Words of the Buddha. This can be from the Pali texts as well as from personal examples of the Buddha’s life.”

Ven. Dhammajoti proposes a three-point intellectual map to navigate the boundary between “the original” Buddhism and Buddhism as it is lived today:

1. All extant canonical texts are more or less sectarian-wise colored.

2. The Buddha’s True Dharma may happen to be preserved in any Buddhist textual tradition (Pali, Sanskrit, Chinese, Tibetan).

3. We can humbly learn from the great masters belonging to any sect or school, provided that they can exemplify and embody the True Dharma—provided they are within the continuous “emanation” (nishyanda) of the Ultimate Truth traceable back, via the tradition containing praxis and realization, to the Buddha’s Supreme Enlightenment.

Ven. Dhammajoti believes that Buddhism, in its earliest recorded expressions, had non-sectarian instincts. “We may consider the argument by Samghabhadra, a great Abhidharma master, that the Abhidharma too is Buddha-word (buddha-vacana):

As the Abhidharma [texts] were compiled by the great disciples on the basis of the Buddha’s teaching, they are approved by the Buddha; they are also buddha-vacana. As they are in accord with the knowledge which knows fully (pari-√jñā) the causes and effects of defilement and purification, they are like the sūtras. If what has been approved by the Buddha is not called buddha-vacana, then innumerable sūtras would have to be abandoned!

(Nyayanusara [順正理論])

He also quotes one of the earliest Mahayana arguments for Mahayana texts as being buddha-vacana in the ancient Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita that its new message of prajnaparamita is the genuine Word of the Buddha.

Subhūti to Śāriputra: “Whatever… the Bhagavat‘s Disciples teach . . . all that is to be known as the Tathagata’s direct effectuation.

For, whatever Dharma taught by the Tathāgata, they, training in it, realise its True Nature (dharmatā), and hold it in mind. Having realized and held its True Nature, whatever they teach . . . is not contradictory to its True Nature. It is just an emanation/outpouring of the Tathāgata’s Dharma teaching. Whatever they are expounding as the true nature of that dharma, they do not cause it to contradict with the True Nature of Dharma (Reality).”

(Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita)

In August 2023, Ven. Dhammajoti was awarded an honorary doctorate of Literature (D.Litt) by the University of Kelaniya in Sri Lanka, where he began his career. I asked him to give a general survey of the present situation of the discipline in Theravada countries. Sri Lanka was the country at the forefront of our minds, since it is a country to which he has devoted much of his working life.

“Buddhist Studies is presently thriving in Theravada countries; particularly Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Myanmar. However, in some ways, the scholarly standard has also been declining and somewhat disappointing,” he said. One reason, he believes, “is, understandably in the post-independence era, the nationalistic outlook of the Sri Lankan university system since the past half century or so, and for many years only a few academic programs were taught in the English medium. Prior to that, there had been highly appreciated learned foreign scholars among the permanent academic staff in the major universities such as the University of Peradeniya (formerly known as the University of Ceylon) and the Vidyalankara University. In my own case, for instance, I was the only foreigner recruited, first as a permanent senior lecturer, then an associate professor, and finally as a professor. I am very grateful to the senior professors and University Council members who had to argue on my behalf and successfully proposed me as an exception. On a more positive note, in the last couple of years there have been renewed efforts to recruit foreign scholars at least on a visiting basis. There is now also consistent encouragement to the bright Sri Lankan younger scholars to receive postgraduate training overseas.

He suggested that Sri Lanka remains the leader in modern Buddhist studies, not least because of their glorious past inheritance from the Vidyodaya Pirivena and Vidyalankara Pirivena (a pirivena is a center for monastic education). These two institutions were established about 150 years ago by a pair of erudite scholarly monks, Ven. Hikkaduwe Sri Sumangala and Ven. Ratmalane Sri Dharmaloka, respectively.

These two leading Buddhist pandits were profoundly learned in Pali, Sanskrit, Buddhist philosophy, and English, as well as being endowed with spiritual vision. “Under these two monks who integrated Buddhist learning with Buddhist praxis, the two pirivenas became at the time international Centres of Excellence for Buddhist Studies, attracting some of the most brilliant students and scholars, locally and internationally, including the Ceylonese scholar Sir Don Baron Jayatilaka, Prof. Rhys Davids from England, and Rahula Sanskritya from India. In 1959, both pirivenas were elevated to the status of public universities: Vidyodaya University and Vidyalankara University. In 1978, they came to be renamed as the present University of Sri Jayewardenepura and University of Kelaniya respectively,” said Ven. Dhammajoti.

The foundation laid by Vidyodaya and Vidyalankara has not only led to many more recent pirivenas (which welcome local and foreign monastics) being established. Almost all public universities offer Buddhist studies, Buddhist philosophy, and Pali and Sanskrit studies up to PhD level. They tend to be under departments named “Pali and Buddhist Studies.” Since 1975, the Postgraduate Institute of Pali and Buddhist Studies, a part of the University of Kelaniya, has provided postgraduate Buddhist studies programs, and annually attracts many foreign students from all over the world.

Ven. Dhammajoti recounts that in 1982, hoping to provide a tertiary level learning environment conducive to bhikkhus, the government of Sri Lanka established the Buddhist and Pali University of Sri Lanka. It was initially restricted to monastics. But in accordance with the revised Parliament Act of 1995, it was restructured with the structure of the other universities of Sri Lanka. Ven. Dhammajoti views this as unfortunate. “Since then, the original ideal seemed to have been forgotten, and along with this have come a host of problems which are more or less commonplace in secular universities.”

Ven. Dhammajoti recounts that in 1968, an act of parliament brought into existence a monastic institution called the Buddhashravaka Dharma Peeteya. Its website explains:

. . . the government at that time decided to establish Buddhasravaka Dharma Peetaya under the Parliamentary Act No. 106 of 1968 with the great expectation of Buddhist education . . . Owing to many unavoidable circumstances during the period from 1994 to 1995, Buddhasravaka Dharmapeethaya [sic] was not capable of achieving its objectives and it just turned to be an institution incapable of enhancing education of monks. With the prevailing situation, we lost another higher educational institution for the Buddhist monks.

Having thought that they should establish the smooth flow of Buddhist dispensation, the then government decided to re-establish the Buddhasravaka Bhiksu University under the directions given by the expertise monks. So, the Buddhasravaka Bhiksu University was established under the Parliament Act No. 26 of 1996 with the sole objective of creating Buddhist monks with knowledge and discipline. . .

Accordingly, with the expectation of creating a Sangha community with academic knowledge and discipline, the Buddhasravaka Bhiksu University was established on 1st of July 1997 . . .

(Bhiksu University of Sri Lanka)

“As far as Sri Lanka is concerned, it should be clear from my account that modern pirivena training and monastic tertiary education have fallen short of the vision of the great masters like Ven. Sumangala and Ven. Dharmaloka. I fear that the situation in other Theravada countries is not any better,” said Ven. Dhammajoti in his assessment.

“There are undoubtedly similar institutions for monastic academic training to be found in other Theravada countries, such as Mahachulalongkorn University and Mahamakut University in Thailand, or the International Buddhist Missionary University in Myanmar. These countries have certainly produced their own scholarly monks and Buddhist professors, some of who are well established internationally,” he acknowledges. “But, by and large, relatively more internationally established scholarly monks and lay scholars (of the calibre of Prof. K. N. Jayatilleka, Prof. G. P. Malalasekera, Prof. N. A. Jayawickrama, Ven. Prof. Walpola Rahula, Prof. Y. Karunadasa, et al.) are to be found in Sri Lanka, where more conscious efforts are being made to groom intellectually apt monastics through modern pedagogies.”

One thing that Ven. Dhammajoti has been unapologetically and consistently critical of is the influence of the prevalent Western value structure on Buddhist education. I take him to mean two things: the general Western attitude that has now moved even postmodernism itself into a kind of Nietzschean void of meaning and objectivity for the 21st century (tinged with flavors of cyberpunk and the absurd), but also the Western Buddhist studies model of historical examination and critical rigor, which I and many others were schooled in. The irony is that I am convinced that quite a few Western-trained specialists, be they religious professionals, academic staff, or monks with PhDs that see themselves as spiritual teachers first before being scholars, might find themselves resonating with his concerns.

“There is an increasingly biased focus in mass producing panditas and scholars, partly thanks to the conditionings of Western values. The leading pirivenas are increasingly like the leading secular high schools and colleges in respect of vision and mission, and are interested primarily in exhibiting ‘success’ and excellence in examination performances. There is little spiritual guidance, little personal exemplification of Buddhist spiritual values, let alone compassionate inspiration, coming from the teachers to the young trainees,” he notes.

“From this perspective, we must understand sympathetically—rather than blaming—the large number of young monks disrobing annually, after gaining admission to the university or obtaining their degrees, or being politically ‘radicalized’ after being deeply disillusioned with monastic life,” he says. “In summary, with a few honorable exceptions, these modern institutions of higher learning, monastic or secular, have generally failed to produce learned monks who are at once great scholars (by modern standards) and spiritually committed practitioners.”

To rectify the direction of development in monastic education, Ven. Dhammajoti urges us to learn from the Buddha’s own life and examples. The Buddha exemplifies the teacher through inspiration, rather than rigidly concerned with legislation of disciplinary rules. He is the inspirer (samadapaka) par excellence. In the Kakacupama-sutta, he states that his mind at one time had been gladdened by the bhikkhus; because he did not so much “need to give instructions to [them], but simply to arouse mindfulness in them (satuppada-karaṇiyam eva).”

The Venerable likewise urges that we could look to the Buddha’s explanations to essentially similar concerns in the Bhaddali-sutta, attributed to the intelligent and highly spiritually sensitive Bhaddali. The latter asks: Why is it that formerly there were fewer training factors but more bhikkhus were established in perfect insight (annaya santhahimsu)? Why there are now more training rules but fewer bhikkhus are established in it?

The Buddha’s explanation spells out what may be regarded as among the core values of the Dhamma:

When beings are deteriorating . . . the training factors definitely become more, and less bhikkhus are established in perfect insight. The teacher does not make known a training factor to the disciples so long as some outflow-causing phenomena do not manifest here in the Saṃgha. . . . When [those negative development] manifest, the Teacher makes known the training factors . . . to counteract those outflow-causing phenomena.

Those outflow-causing phenomena do not manifest so long as the Saṃgha has not become big (mahattaṃ patto); . . . has not reached the height of (worldly) gains (lābhagga); . . . the height of fame; . . . great [intellectual] learning (bāhusacca), the height of recognition (rattaññutā).” How pertinent these words of Wisdom are even to us modern Buddhists!

(Bhaddali-sutta)

“In the late 1970s, I wrote an article called “The Bhikkhu Education in Sri Lanka,” in which I argued that the Buddha’s doctrine of the five spiritual faculties (faith, vigor, mindfulness, equipoise, and wisdom) should be borne in mind as an important guiding inspiration for monastic education,” says Ven. Dhammajoti. The ideal of Buddhist education should be one conducing to the perfect harmonization and integration of the total being (not one-sidedly concerned with intellectual training and legislative disciplinary control)—intellectually, emotionally, conatively; founded upon meditative praxis with spiritual vigour and guarded by mindfulness.

Ven. Dhammajoti has faith that the Sri Lankan universities have the advantage of a continuous tradition of scholarly studies. They have also the advantage of being comparatively connected to the Anglophone world of research and Western methodologies. “Many of the great scholars, such as Prof. K. N. Jayatilleke, received their higher training in reputed Western universities. Others obtained their PhDs from other Asian countries. Kelaniya and others have already gained considerable international recognition as major centers for Buddhist studies, at least in Pali and Early Buddhism,” he says.

There is certainly leadership potential in this respect, Ven. Dhammajoti concluded. But he noted that the institutions themselves need to be sufficiently aware of their own potential—and commit to developing it academically and spiritually. “As regards the integration of Buddhist studies with spirituality, they must further consciously steer clear of the conditioning of Western values,” he stresses.

“In the domain of monastic education, I personally believe that a major problem is a sort of leadership crisis: There need be more senior monks—scholar and practitioner rolled into one—who can exemplify the integrative development which accords with the five-faculty doctrine, and thus capable of inspiring the younger generation. They need not be perfect; but the monastic trainees should be able to concretely feel, and be inspired by, their sincerity, faith and wisdom.”

Related features from BDG

Related news reports from BDG

Ven. Prof. K. L. Dhammajoti Receives Honorary Doctorate from the University of Kelaniya in Sri Lanka

Related blog posts from BDG Tea House

Diverse Perspectives and Approaches to East Asian Buddhism and Beyond