Alexander Gardner is the director and chief editor of Treasury of Lives, an online biographical encyclopedia of Tibet, Inner Asia, and the Himalayan region founded in 2007. He is also the author of a new biography The Life of Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche the Great, published by Shambhala. In this extended interview he reveals how he came to head the Treasury of Lives project, his extensive contact and interactions with pioneering figures of American endeavors to preserve Tibetan culture and texts, and how he became intimately involved with telling the story of Jamgon Kongtrul (1813–99).

Buddhistdoor Global: What foundational academic or religious experiences led you to complete a PhD thesis in 2007, and in the same year, begin work on Treasury of Lives?

Alexander Gardner: I started studying Buddhism in college, at a small liberal arts school in Vermont called Marlboro College. I arrived there having a daily meditation practice, from a course in Transcendental Meditation that my father and I had done. I was drawn to Buddhist theories of the nature of mind and what happens when one closely observes mental phenomena such as thoughts and emotions, but I did not know anything really about the religion. My professor encouraged me to think about doctrine and practices historically rather than as timeless abstracts.

As fascinated as I am by Buddhist descriptions of reality and the explanations of why there is suffering and how it can be overcome, I am equally interested in who taught the doctrine and why. Ideas never exist in a vacuum, after all. They arise in the world, from real lived causes and conditions, and they are adopted and altered over time because people find them valuable, because they resonate with people’s lives. That is actually one of the reasons I think the Tibetan tradition of revelation—“treasure”—is so compelling. It acknowledges the temporal nature of religious teachings and the need to constantly modify them in response to the needs of a particular time and place. Grand ideas can be profound and elegant, but if they are disconnected to people they are of little practical use. Or, as my former boss Donald Rubin always said, “don’t live your life in the abstract.”

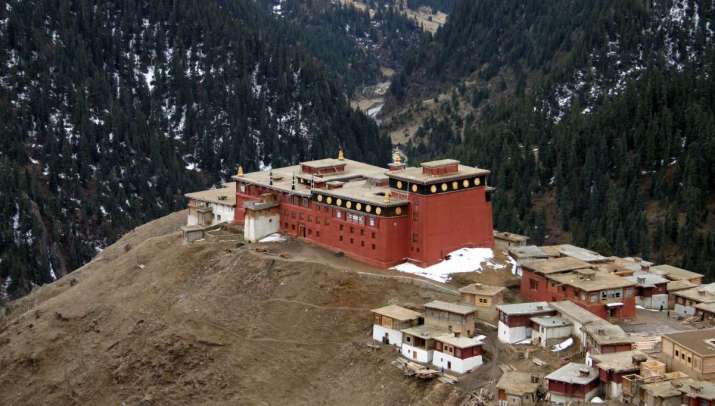

So as I continued to deepen my involvement in Buddhism and traveled in India, Nepal, and Tibet, I always took an historical and biographical approach to my explorations, and that ultimately brought me to enroll in the PhD program at the University of Michigan. After I completed my master’s degree in 2000, I took a year to study language in Chengdu, at Sichuan University and the Southwest Nationalities University. I was able to travel through Tibetan regions close to Chengdu and I became fascinated with the landscape and the people. Tibetan Buddhism is very physical, even when it comes to legendary masters such as Padmasambhava; Tibetans care about where Padmasambhava went, which caves he sat in. Tibetan religion is very deeply rooted in place. The local spirits and deities and Buddhist saints are part of people’s daily lives, connected to communities through the land that they both inhabit.

One cannot travel around eastern Tibet—Kham—for long without hearing the names Jamgon Kongtrul, Khyentse Wangpo, and Chokgyur Lingpa. Those three together had an enormous impact on the religious environment of Kham during the 19th century with their magnificent activities. They determined the ritual systems that people used and the literature they read. And, as I learned through my dissertation research, they also remade the religious geography of the place. They sanctified scores of places—caves, mountains, lakes, hermitages, monasteries, stupas—and were constantly out in the world practicing and teaching and performing rituals for the local and regional communities. I wanted to understand how their activity was connected to the landscape and the culture of the place, and what was happening politically and culturally there that propelled them to do what they did.

After I completed my degree I was living in New York and was fortunate enough to get hired by Gene Smith at the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center, now known as the Buddhist Digital Resource Center (BDRC). The BDRC was at the time housed at the Rubin Museum of Art and in the offices of the Shelley and Donald Rubin Foundation, and over the course of the year I met the Rubins and the director of the foundation at the time, Bruce Payne. When my position at the BDRC finished, Bruce hired me to help out with the foundation’s activity in Asia, and to take over a website that had been started by the great scholar and teacher Matthieu Ricard and his colleague Vivian Kurz, with help also by Moke Mokatoff. They had been tasked by Donald Rubin with creating a website to help people learn about the Buddhist tradition that was so beautifully depicted in the art that hung in the Rubin Museum.

The story Don told was that he was walking through the museum one day with a Tibetan monk and asked him to identify a man whose portrait was on the wall. The poor monk didn’t know who the lama was and received a gentle scolding for it. Of course, I don’t think your average European Catholic monk would be able to identify every saint found in art, so Don’s criticism wasn’t entirely fair. Still, it inspired Don to ask his friends to create an educational website, which they did and which I was then tasked with developing when I was hired in early 2007. Matthieu, Vivian, and Moke had created a very nice model, with descriptions of people, deities, teachings, and texts, but I decided that in moving forward, because Himalayan Art Resources (HAR) already described deities, and the BDRC was building out their database on Tibetan literature, we would focus on the people. We renamed the site “The Treasury of Lives,” a name that was an obvious borrowing from Kongtrul, who is famous for having produced five collections of literature known as the “five treasuries.”

My thinking was that through accessible and well-detailed narratives of the lives of Buddhists in Tibet and the surrounding regions, readers would be able to get a sense of the lived experience of Buddhism. They would get the teachings through stories of how the teachers and practitioners actually engaged with them. Buddhist communities across Asia have always told stories of their teachers in order to inspire and propagate the teachings, so I figured The Treasury would fit right in with that tradition. Although we started with the lives of the great masters, we soon realized that there is inspiration to be found in the lives of the diligent monk, or the reclusive hermitess.

We also found that to better understand the context of the life we needed to include biographies of politicians, artisans, explorers, craftspeople, and so on. To make it beautiful we use art from the Rubin Museum and other collections that are displayed on HAR, and we link extensively to that website and to the BDRC, so that scholars and other readers could always find out more information. Of course, we found we had to explain a lot of the historical context along the way, so we have short descriptions of the religious traditions, the history, and the places that are mentioned in the biographies, and we have developed a pretty great interactive map that readers can use to explore all the geographic data we have.

BDG: Many of the contributors on Treasury of Lives are established names in Buddhist studies or Tibetology. Do you have any particular research methodology, formal or informal, when accumulating and publishing materials on this website?

AG: One of the best things that Matthieu, Vivian, and Moke did when starting the website that became The Treasury of Lives was to engage some of the best scholars writing on Tibetan Buddhism today, such as Dan Martin and Cyrus Stearns, as well as some very well-informed practitioners that they knew. Right from the start, the content of The Treasury has been a collaborative effort and I knew that in order for the global community of scholars and practitioners to embrace the site they would want to see that level of collaborating continue. Diverse points of view and different voices bring a greater complexity and richness to the site. And I didn’t want anyone anywhere to think that the site favored any particular tradition or view. We have essays now from more than 100 different authors, including Tibetan, Bhutanese, Chinese, and Mongolian scholars, as well as authors from across Europe and North America. We don’t require academic credentials, as long as the author knows the material; there are practitioners out there who don’t have advanced degrees but know the biographical material of a particular historical person backwards and forwards. What we don’t take are translations; we want the author to digest the material and then narrate the life, bringing in scholarship and multiple primary sources to craft an original piece.

We also don’t do traditional hagiographies, which can be one-dimensional and erase individual characteristics. The biographies have to be readable, making full use of scholarly conventions but be free from jargon or other limiting elements. My fellow editors and I work with authors to arrive at the final essay, to whatever degree that is required, and for the past five years or so we have been sending essays out to be peer reviewed. Now that the site has become better known we get offers from all over to contribute essays, which is really great. There are still some large absences on the site, but I am happy to say we have people now working on biographies of the major missing figures, such as Longchenpa and Karma Chakme. The Treasury is an independent non-profit, and we need donations to keep the site alive.

BDG: Apart from the fact that there were no English biographies of Jamgon Kongtrul until this the publication of this book, was there any personal reason that motivated you to cover this figure?

AG: Before I started my dissertation work I was actually mainly interested in Khyentse Wangpo, Kongtrul’s dear friend and in many ways his inspiration. His name would always come up in the stories my own teachers, Nyoshul Khenpo and Khenpo Sonam Tobgyel, would tell, and I felt a connection to him, I don’t really know why. I loved the stories of his fierceness. Khyentse’s activity is inseparable from that of Kongtrul and Chokling, so I couldn’t help but study the three of them together. And when I settled on my dissertation topic, the Twenty-five Great Sites of Kham, it was Chokling and Kongtrul who both produced the gazetteer of the places (Chokling revealed it, and Kongtrul revised it).

There is a huge amount of biographical literature on Chokling, and Kongtrul kept a detailed diary, which he lightly revised toward the end of his life, but the only biography of Khyentse is one that Kongtrul wrote, and it is mostly a listing of Khyentse’s revelations and teachings received and given. So the more I read I found myself knowing Chokling and Kongtrul better.

I think it is impossible to delve into these people’s lives without developing a profound admiration for them. They were so ambitious, so dedicated to their religious institutions and teachings, and they never stopped working for their communities and the religion. It is almost impossible to comprehend how many places they visited, how many new treasures they collectively produced, or how many existing teaching traditions and ritual systems they collected, edited, published, and transmitted. And they traveled on foot or by horse, they lit their desks by candle or oil lamp, and they wrote by ink on handmade paper that was expensive to acquire. They also spent years in personal retreat doing the practices that they were teaching and publishing. Practice really was integral to their work.

One of my missions in the book was recovering Kongtrul’s humanity from all the legend and myth that has grown up around him. Great Buddhist teachers often get stripped of the stuff that makes them like the rest of us, as though we are supposed to think of them as fully perfected from birth. I do not see much inspiration in that sort of thing. Buddhism is a path of transformation, and if the people who are supposed to model the path started out perfect, what hope is there for us?

There is a passage in the book that I particularly love when Khyentse Wangpo is distraught following the sudden death of one of his brothers. Kongtrul had just returned from two years on the road in a remote region, and Khyentse wrote that he needed to come over “to receive some transmissions.” Because of the religious context, I think it would be easy just to think they were working. But there was a personal and emotional layer here. Khyentse needed comfort from his friend, and that is why he went over. The transmission was the thing they did when they got together; it was not the main purpose of the meeting. If he had said he wanted to come over and watch a movie we would have understood this immediately. But because the two of them were great religious figures, we forget to think of them as human beings. There is a lot of this is the diary, particularly around how these two friends supported each other emotionally as well as professionally.

Kongtrul’s diary was beautifully translated by Richard Barron over a decade ago, and it is well worth reading. But a diary is not a biography, or even an autobiography as we use the term in the West, although that is the title it was given in translation. There are several nice sketches of Kongtrul’s life, most usually found in introductions to translations of his work, and the general outline of his life is fairly well known. The best of these, I think, is by Elio Garusco in his preface to Myriad Worlds, the first volume of the translation of Kongtrul’s Treasury of Knowledge. But with the diary and the other primary resources, there is a huge amount of information about Kongtrul’s life available, which is pretty rare in Tibetan contexts.

Tibetans produced a huge amount of sacred literature, but there were not the sort of public documents that biographers in the West can rely on, which explains why full biographies of Tibetans are extremely rare. In his diary Kongtrul gave us a lot of clues to his thinking, his emotions, his motivations, but he rarely states them plainly. He also organized the work chronologically, just writing down all the things that happened in their sequence (although not always accurately). It is a fantastic resource for the biographer, like Ralph Waldo Emerson’s diaries are for his biographers. But reading diaries is hard. It is hard to get a sense of what’s going on, the relations between the events, the significance of the people or places or books that are mentioned. It was a lot of fun to draw all that out, to write a portrait of such a fascinating and influential teacher.

I was also able to bring in the books the three wrote, biographies of associated people, and many many amazing works of translation and scholarship. I am proud of what I produced, but I also am not so foolish to think that mine is the last word. Hopefully in a few decades another biographer will take up Kongtrul again and add whole new layers to the narrative. Someone should do a literary biography, going into all his own compositions more deeply than I did.

BDG: In the book you emphasize just how tapped in Jamgon Kongtrul was to the diverse streams of thought of his time, and how he was an outsider of sorts. Is there any historical figure whom you would call an intellectual or spiritual heir to Jamgon Kontrol’s thought?

AG: I’m glad you picked up on that theme. I think it is probably inevitable for someone so connected to so many different traditions and institutions to at the same time feel a little alone in it all. I mean, first of all, how many real peers could a person like Kongtrul have? Only Khyentse Wangpo had a similar capacity to absorb so much and maintain a sense of coherence in it all. Institutionally, at various points in his life, Kongtrul was Bon, Nyingma, Karma Kagyu, and Shangpa Kagyu, and he received teachings in most of the other Kagyu traditions as well as Sakya, Jonang, and Geluk. He was respected in so many diverse religious communities, and was constantly receiving supplicants requesting one transmission or another. He was the go-to guy for transmissions and widely known as an effective ritualist, employed by royalty and government officials, prominent families, and religious figures. I suspect there is a certain loneliness in genius, a sense of isolation when there is no one else who can keep up with you. Maybe when you belong everywhere you do not really belong anywhere in particular, even as you look out to the world with great compassion. Khyentse Wangpo was a huge support for Kongtrul for the whole duration of their friendship, some 50 years of it. Once Khyentse died, in 1893, Kongtrul quickly slowed down and only lived another six years.

Because of the huge span of his activity, Kongtrul was regarded by many with some suspicion. People are often uncomfortable with individuals who will not reduce their allegiance to a single place or doctrine. Kongtrul maintained the distinct integrity of each religious tradition, but his refusal to confine himself to the Karma Kagyu community of Pelpung was a problem for partisans there. Due to his embrace of so many traditions, a large and powerful faction of monks at Pelpung doubted Kongtrul’s loyalty, despite his decades of service there.

The more famous Kongtrul became, the more donations he received at a time when the leadership of his monastery, Pelpung, was in shambles. The 10th Situ, the reincarnation of Kongtrul’s beloved guru Situ Pema Nyinje, was not a great success, and he was not able to bring in the financial support a head lama is supposed to. So there was a lot of resentment, fairly or not, against Kongtrul for receiving what otherwise might have gone to the Situ estate at Pelpung. All that, plus his growing treasure activity, led a faction of monks to accuse him of impropriety and he was exiled from Pelpung for 11 years.

In terms of someone who might be comparable, my mind immediately goes to great artists rather than other religious leaders. Artists receive the world and then retransmit it in a new form. They have a vastly increased capacity to absorb and process and make sense of it all. They take the stuff we all experience in our own small ways and they reveal in their art what they have seen. I think that is what Kongtrul did with his literary collections. He took it all in, processed it all, preserved it but reorganized it all in a way that was fresh and comprehensive and lasting. What he did not do was start anything new—no new religious traditions or orders, like Saint Francis or Martin Luther did. He was very traditional and in that sense I think he can be likened to a buddha rather than the Buddha, if you know what I mean. He reaffirmed the tradition, he didn’t revolutionize it. He modeled it for everyone, not in the sense that we are all supposed to go out and read everything, but in that we are supposed to refrain from partisanship and parochialism.

BDG: With today’s hindsight, how effective was Jamgon Kongtrul in balancing the importance of ritual and institutional Buddhism with the need for a nonsectarian or, to use bolder terminology, ecumenical approach like Rime?

AG: I think Kongtrul was successful in that he continues to serve as a model for the nonsectarian outlook. I think attention to his life has alerted us to the fact that Tibetan Buddhist traditions have always been impermeable—that people have always crossed traditions to learn from masters of other monasteries, and that it is OK to do so. The well-known Geluk sectarianism of the 18th century was not necessarily representative of Tibet as a whole. I think rather there was always a mix of partisanship and ecumenicalism, in various degrees.

Still, few have exemplified the nonsectarian view better than Kongtrul. But I do think Kongtrul has been misunderstood. I do not think he was a social reformer in the sense of the founder of a movement, and he certainly did not advocate for rejecting institutions or rituals in any way. A lot of Americans and Europeans projected that onto him in the 1970s, a time when smart people were rejecting oppressive social structures and looking for new ways of practicing and exploring faith. But Kongtrul knew intimately the value of religious institutions and public rituals. These are the things that sustain religion. Rejecting those things would be like rejecting the body in the name of cultivating the mind. How could that be possible? The Buddha tried to starve himself into salvation only to find he was depriving his mind of the nutrients it needed to function, that he was destroying the location for his enlightenment. Buddhism without monasteries and Dharma centers and hermitages and regular ceremonies would just be some ideas in a book no one reads.

Kongtrul collected and published in a way that both reaffirmed tradition and pointed toward a nonsectarian model. He did a huge collection of Kagyu tantric liturgies and a huge collection of Nyingma liturgies. Khyentse Wangpo did a Sakya version. These are three of the dominant traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. At the same time Kongtrul also did two collections that were distinctly ecumenical and that was sort of radical, albeit within a traditional framework: the Treasury of Knowledge and the Treasury of Advice. Tibetans have long produced drumta, or tenet systems, what scholars call doxographies. These lay all the known Buddhist teachings side by side as valid teachings, but in a hierarchy of effectiveness. The three-vow genre also does this (Hinayana, Mahayana, and Vajrayana), as does the three turnings literature (Hinayana, Madhyamaka, and Yogacara). There are other examples specific to the Tibetan traditions as well, such as the eight chariots of accomplishment that Kongtrul used in the Treasury of Advice and in a small religious history he wrote.

Kongtrul’s nonsectarianism was rooted not just in the above genres of doxography, but also in theories of nondualism and two truths. Kongtrul presented his understanding of Buddhism and promoted his favorite teachings from all the traditions he knew in a way that did not denigrate any of it. He had his favorite teachings that he felt were the culmination of the Buddha’s teaching—the Dzogchen teachings of the Nyingma tradition and the zhentong, or other-emptiness view of ultimate truth as taught by Jonang and others—but he did not claim that any of the other teachings or views were less than worthy of veneration.

Buddhist non-dualism does not mean not recognizing the difference between things, it does not mean somehow denying the separation between self and other. It means recognizing that the separation and differences are relative, impermanent, and conditional. It means not engaging with “this is good” and “that is bad,” and not disparaging things that are not one’s own. This is exactly what ecumenicalism is in religion. One does not abandon one’s own traditions, but rather recognizes the value on all traditions and treats them with dignity.

It is only from the perspective of one’s own self that one can have a view at all; you have to stand somewhere in order to participate in the world. When the Madhyamaka masters say they have no view, it does not mean that they had no position or no opinion about things. It meant that they did not claim their view was the ultimate truth, the absolute always true for everyone sort of truth. How could it be? Everything conditioned is relative to time and place, and all language and thought are conditioned. Any position regarding the ultimate would itself be relative. That did not make it not true—relative truth is very real; it is the truth of history, of people, of communities and culture. It is what we live and experience. The ultimate truth—the truth of emptiness that people love to talk about—is simply the fact that all things are relative. The ultimate is just an idea. This historical perspective is very much in line with the notion that the Buddha taught 84,000 dharmas—a teaching for each person, each situation. All of them were true, and none of them are held to be universal or absolute.

People tend to forget the Heart Sutra’s important teaching that “form is emptiness, emptiness is form.” Everyone wants to focus on emptiness or ultimate truth, and forgets that the expression of emptiness is the world. There is no emptiness, no ultimate truth, if there is no activity. Every view is a pure view if it is taken up with a nonsectarian attitude—if, ironically, it recognizes that it itself is fully within the relative realm. That is what it means to perceive emptiness. One engages with “mine” and “best” while recalling that “mine” and “best” are just a matter of perspective and not permanent. That is what Kongtrul did so beautifully. He followed his insatiable curiosity, followed the path that worked best for him, organized the teachings in a way that made sense to him and never disparaged any part of it.

So, Kongtrul’s wide embrace of institutions and rituals and regionalism, these were all the venue in which he expressed his ecumenicalism. You do not need to be a genius like Kongtrul to be ecumenical, and you certainly do not have to abandon your own affiliations. Kongtrul never did. You just need to stop being so attached to your own self and recall that everything is just a matter of where you are standing.

See more

Treasury of Lives

The Life of Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche the Great (Shambhala)