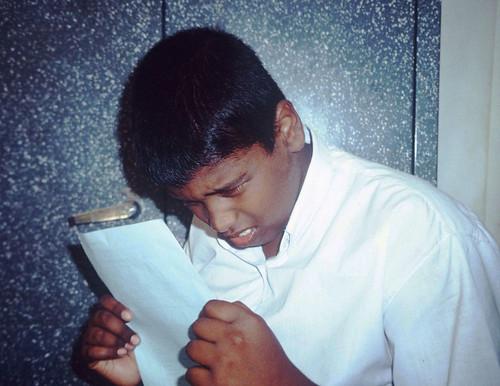

With slow, clumsy movements, Chandrika reaches for the pencil held in front of her. She misses, and narrows her gaze. After three attempts she manages to grasp the object with her tiny hand, and giggles. Born with strabismus, or “squint,” the frail-looking five-year-old suffers from amblyopia, or lazy eye, but has never received treatment. It was simply not a priority for her mother, Kumara. Employed as a daily-rated farm worker, the single mother struggles to earn enough just to put food on the table for her three young children and an ailing 60-year-old mother. But noticing a persistent redness and swelling in Chandrika’s right eye over the past two weeks, when she heard about the free eye camp in Panama, just 25 kilometers from their home on the east coast of Sri Lanka, Kumara decided to give it a try.

In a makeshift clinic in a community hall, Dr. Nalin Goonesinghe prescribes antibiotics and eyedrops for Chandrika. She has conjunctivitis, probably due to contact with contaminated water. But he is more concerned about her squint: she will need corrective eyeglasses to help align her eyes. “Squints are common, particularly in young children,” he reassures Kumara. “The vision is diverged because one eye looks at one angle and the other looks elsewhere. Left untreated, it had affected Chandrika’s vision. There are also other related problems, such as coordination of movement and learning disabilities. In serious cases, it can even lead to blindness. But with early intervention, we can prevent further deterioration and even correct the defect.”

Because of its prevalence, the detection of strabismus is emphasized at the one-day workshop on vision screening that Nalin conducts as part of the community eye-care program in rural Sri Lanka. The community care program in each village stretches over several months and entails a number of visits by the eye team. In the first stage, selected volunteers, mostly teachers from either local schools or Dhamma schools in the area, are trained in basic vision-screening procedures and identifying common eye problems. The participants are provided with the necessary test kits to conduct screening within the community or in schools.

After these initial checks, those with vision problems are identified and given appointments for a thorough examination by the eye doctor on his next visit, usually about two months later. Depending on the diagnosis, corrective eyeglasses may be prescribed, or in more complex cases like cataract or glaucoma, surgery may be needed. Operations are usually performed at the local base hospital or at other surgical facilities in the vicinity. About three to six months into the program, postoperative evaluations and reviews are carried out. Treatment at these mobile eye camps is free, including brand-new spectacles, prescriptive lenses, intraocular lenses, and medication.

Juggling the demands of his private eye clinic in Colombo, family commitments, and the mobile eye camps, Nalin is able to conduct a camp only every two to three months. Supported by his own staff, and occasionally by his wife and two children, each trip can take three to five days, depending on the location. It is a logistic challenge for the team, as they have to take all the necessary ophthalmic equipment with them every time.

With an MSc in Community Eye Health from University College London, Nalin is well aware of the plight of impoverished families in rural Sri Lanka. Born into a family of medical practitioners who are also devout Buddhists, the key inspiration behind his commitment to help the poor and vulnerable came from his mother, Dr. Sirima Goonesinghe. Now aged 90 and retired, Sirima, also an eye surgeon, was a founding member of the Dharmavijaya Foundation, a Buddhist-based charity whose mission is to establish a righteous society by applying Buddhist principles to economic development. An inspiring figure, Sirima pioneered many rural development and community eye-care programs throughout the country.

Nalin explains: “Most people in the rural communities lack eye health awareness. They have little knowledge of eye diseases and do not understand the importance of regular eye examinations. Sometimes, due to ignorance or superstitions, they do not seek treatment. Many people think that squinting will be corrected over time and does not require any special treatment. There are also some who believe that squint eyes bring good luck, or that it is the result of some bad karma that children are born thus. Many young children suffer needlessly from eye conditions simply because parents do not even know their children are having visual problems. This is unfortunate as it causes immense suffering for the child, both physically and emotionally.”

It is indeed ironic that in Sri Lanka, which has been hailed as the country that supplies sight to the world because of its renowned eye bank, more than half the population cannot afford eye care. Even though surgery in public hospitals is free, patients have to purchase lenses and other necessities, which are expensive and well beyond the means of the poor. Another barrier to seeking treatment is the difficulty of traveling long distances. Apart from Colombo, there is a lack of specialist eye services throughout the country. Many base hospitals in remote villages do not have an eye unit, or even an ophthalmologist.

“Because of the many difficulties, the poor often choose to forgo treatment, and eventually they become blind. So instead of waiting for them to come to us, we have to go to the community. Sadly, by the time we reach them, for some with lifelong untreated eye conditions, their conditions have deteriorated so badly that it is too late to do anything,” adds Nalin.

Beyond just giving treatment and free spectacles, the mobile eye camps are a way to reach out to and mobilize the rural communities. “Besides just training volunteers in vision screening, we create awareness of the blinding diseases that exist and ways of preventing them. Community participation is important in eye health promotion. We need to motivate individuals and communities to participate in prevention activities. It is a hugely challenging task. Getting people to change their mindset and behavioral patterns is one of the hardest things to do. But care of the environment, provision of clean water, waste disposal, better hygiene, and proper nutrition all contribute to reducing the incidences of eye diseases.”

Another challenge, one that Nalin finds quite disheartening, is the attitude of some in the medical profession in Sri Lanka. “It is hard to find support from doctors to donate their time and skills for a charitable cause. Yes, this is a Buddhist country, and everyone goes for pujas and offerings. But it seems many have forgotten the true essence of Buddhism—compassion, caring for others, humility, and simplicity. The Buddha said, ‘Whoever would attend to me should also tend the sick.’ The Buddha never shied away from helping the sick and elderly. It is a shame that many doctors in this country have lost sight of the whole tradition of medicine—that is, going to the sick and attending to the sick.”

Despite the difficulties and exhaustion, at the end of every camp there is a quiet exhilaration among the team, knowing that they have opened up a brighter future and a clearer world for many who might otherwise live in darkness. So what has kept this doctor focused on his vision for more than 15 years? Nalin replies: “You get great strength from your patients. It is an emotionally powerful moment when you see the smiles on their faces when they are able to see again. More than a gift of sight, we are bringing a gift of hope. The opportunity to give and to serve, to make life-changing differences in the lives of so many people, this itself is a blessing.”

Images courtesy of The Eye Clinic, Colombo