Whether looking at a depiction of dance in an ancient mural painting, a black-and-white photograph, or a digital print on canvas, three factors are in play: the artist’s eye, the “lens” of medium and style, and the dance as it transmutes from vital physicality to time-transcending image. An exhibition of dance photography held recently in Chicago, curated by a young Chinese woman, featured the subject of looking at dance, and depicting it. Because this column regularly asks its readers to make some study of one image of dance or another, I thought it would be insightful as well as a pleasure to move through this exhibition and follow the perspectives on display.

Feng Yuanpeng is a 21-year-old Chinese student of international arts management at Columbia College Chicago. Raised in central Henan Province and educated in Beijing, she is fascinated with the exhibition industry and has been motivated lately by what an insufficient job she feels Chinese dance museums are doing for the art of dance and its popular appreciation. China stands alone in its number of national, regional, and private dance museums. Just as China is the only nation with a National Dance Research Institute full of world-class scholars and brilliant graduate students, the number and quality of dance museums in China reflects a national priority for the understanding of dance.

One day, a couple years back, Feng learned of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen’s Museum of Pop Culture in Seattle. She made a case study of it, long distance. It was fun and informative. People and families were having a great time; didn’t want to leave. It was theatrical, exciting. “Why?” wondered Feng. “Shouldn’t a dance museum be at least as exciting as a music museum?” She noted that while the level of dance scholarship in China is often high, it is also often dry. She also thought the focus advocated a kind of dominance of scholarship, and not on the core reality of dancers and the artists who left images of them. The focus, she concluded, should be on the artists.

On the power of her own initiative and with the help of the friendly Hip Cat Gallery in Chicago, Feng set out to curate a dance photography exhibition, Stories from the East: Dance Photography in Contemporary China, which opened on 15 October 2017, and ran for a full month.

On a less-than-shoestring budget, three Chinese photographers agreed to be represented by her. They prepared digital and canvas prints of their dance photography, featuring companies from Chonqing, Beijing, Ningbo, and Sichuan. One artist also featured fine graphic art for posters of ancient dances. These striking images graced the promotional material and greeted the visitor to the small offbeat gallery west on Addison, about a mile from Wrigley Field, promising new views on known and unknown dances.

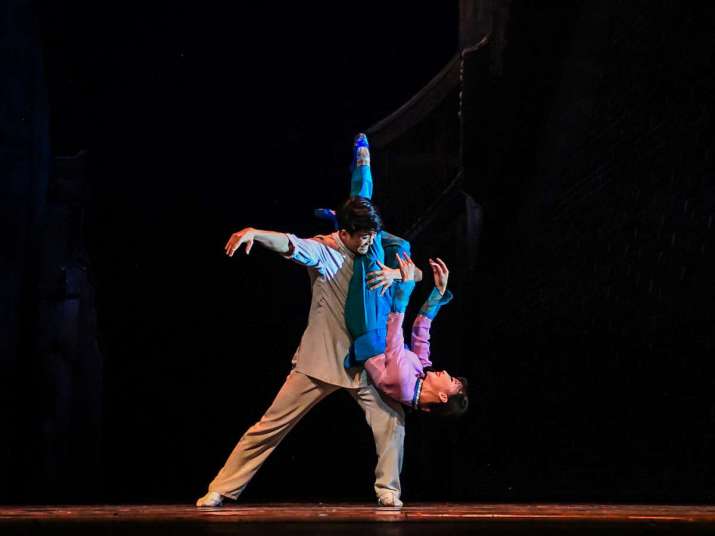

Huang Kaidi is an MFA student at Sichuan Normal University. His 10 photographs of live performance captured the energy and form of the work Home by the Sichuan Song and Dance Theatre, relying his refined perceptions as a choreographer. Dance is robust in China. There are many dance companies, constant dance competitions on television, omnipresent Chinese opera on TV and stage, and there are also many photographers.

Curator Feng has made an effort to show that despite the preponderance of photographers, the ability to capture the moving energy of dance requires an art of its own, as individualized as the artist. Once moving past the glamorous ancient dance posters at the gallery entrance, to the 10 choreography-focused photographs by Huang enclosed in an alcove passageway, it was clear that this exhibition was about the art of dance, not dance scholarship.

Don’t just look; look carefully. Photography, like painting, has technical capacities that allow us ways to see the dance, the ephemeral beating heart at the core of the expression. Feng would present several of these ways through the work of contemporary artists.

Going further into the Chinese tradition of drama being entirely danced, photographer Wang Xufeng presented a series of eight photographs marking moments in the long dramas, General Mulan and Du Fu. These images took up the main area of one wall of the gallery. The photos were encapsulated storytelling, icons for action like subtitles for chapters of novel. Here Feng sought to show clarity and meaning and that photography of dance could provide this to narrative representation, at the same time reveling in multi-art forms and human emotion.

Wang Xufeng is a professional photographer and his work is elegant. He is also the artist behind the stunning posters of ancient dance, Imperial Concubine and Craft Synchophant. Printed on canvas, the performance photos have a painterly quality that warmed the impression and enriched the memory of the performance with the faintest loss of detail. The storytelling is couched in the emotions he was able to capture from the dancers, only after visually marveling at the physicality of the dancing first. Wang has many accolades including being special photographer for the CCTV program Dance World.

Wang Dan, who is employed by the Sichuan Conservatory of Music, stretched the image of dance and explored ways to reach an image of its moving energy. In a set of four photos titled Bamboo Stroll (2016), she placed a posing folk dancer amid a bamboo grove. “Folk” in China implies lots of ballet training and so this “folk” dancer has legs extended and feet pointed in that way Chinese culture pretends not to be influenced by ballet, and yet the juxtaposition of culture, nature, and turned-out legs creates a visual essay in segmented growth (the metaphoric implication of bamboo), segmented identity, and segmented dance training. The simple genius was making it look natural, making it fit, making art of it all. The dance appeared to belong there.

Wang’s other set of four photos, Folk Dances, of Korean, Uighur, and Chinese folk dancers were time-lapse photos showing what would be flashy color in a typical photo becoming a laser ray of moving forces, dancers emanating clouds of liquid light. The identity of the minority culture is clear as well as the blur of the lines and stretch of the bold flow. China touts its “56 ethnic minorities” as demonstration of their diversity as a nation. Yet folk dance has been nationalized and codified, balleticized, and subject to similar types of representation, as if each culture were a museum display. Wang moves past all this and requires the viewer to look again, to see what the dance itself says, to follow the flow of color to the person making it happen; to see cultural identity on a personal level when the symbolic languages blur into color and light, and the spirit of a single dancer animates meaning.

While the standard skills of hanging a show, mounting photography and art, promoting, and discussing the salient themes are seedling skills in young Feng, her digital-print show, produced with excellent artists, clear ideas, a few of her own pennies, and an encouraging gallery, succeeded in making a case that there is a different and considered way to show dance and photography than is done in the major dance museums of China. She is someone serious. With more funding, real photographs, and larger scale images, Feng can do something important.

There is much to admire in her attitude to getting things done, testing the waters, and gradually building the trust of artists, galleries, and viewers. As the museum world continually re-invents itself, and the role of dance and the related arts takes on new hues of meaning with globalization and digitization, Feng’s motivating question remains a good one. “Why shouldn’t a dance museum be at least as exciting as music museum?” Vision is the ability to see something that isn’t there yet; to see through everything to something no one else sees. Feng Yuanpeng has vision and drive. She is someone to watch.