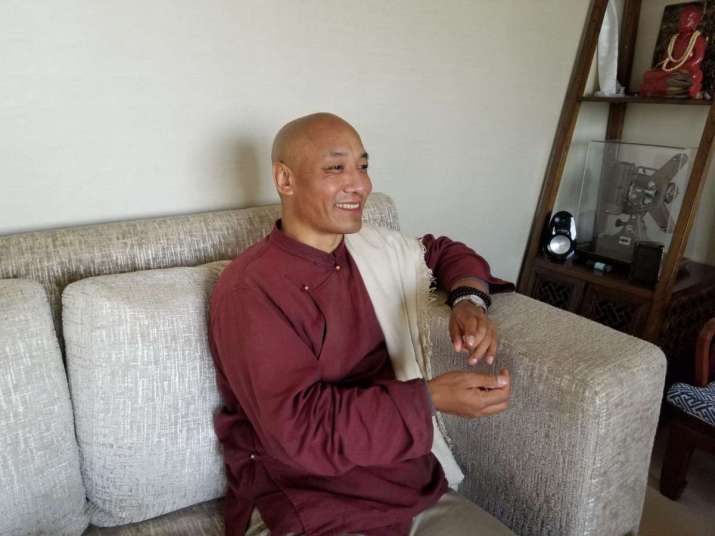

Anam Thubten Rinpoche, founder of Dharmata Foundation (and who also pens a column on Buddhistdoor), has had quite a busy 2018, travelling the world and expanding his sangha beyond his base of Berkeley, California. I am happy to report that thanks to his annual visits and the support of his local disciples, Hong Kong has now become one of his main bases. In November, I spoke with him when he was in Hong Kong for a series of Dharma talks, a retreat, and to visit his sangha, and I mean his sangha in the formal sense: the Dharmata Foundation now has a growing and consistent following in Hong Kong.

Rinpoche has four aspects to his main fulcrum teachings: mindfulness or meditation, compassion, emptiness, and enjoyment. “Meditation has two kinds of levels—the basic, secularized kind of simply observing our emotions and then the much more profound dimension where we engage in deep exploration of the mind. Nowadays people of all backgrounds and professions can meditate, the stereotype of the 1960s hippies is long gone,” says Rinpoche.

“Compassion is an inherent quality that we must cultivate regardless of spiritual beliefs; it pushes us to become better people. When we speak about becoming better people we’re talking about being more evolved people. I really like the concept of evolution and reworking it in a spiritual context. I find enlightenment a bit too grand to bring down to everyday conversation, so I’m not so reluctant to call people ‘evolved.’ As human beings, we have a certain kind of destiny—not in the theistic sense—but we are supposed to evolve in happiness, kindness, morality, and empathy. Our common destiny is to continuously widen the circle of love and compassion. The more we evolve, the happier we become. That’s my idea of what evolution is. It’s a kind of vocation for all beings. We are here to evolve.”

Rinpoche sees emptiness or sunyata as the Buddhist “absolute” or the “ineffable.” The highest truth is not “some thing” to be grasped or to be found, instead it is the ultimate freedom from all concepts. “For Buddhists, the absolute transcendent is emptiness, and the great Mahayana Buddhist masters like Nagarjuna and Shantideva said that realization of emptiness was to touch the Great Mystery.” No matter how good we are, we remain attached to this reality or (to use a popular pop culture reference) matrix of “duality” and of “self” and “good and bad.” Even Buddhists, he says, can approach spirituality with a sense of “holding on” to something, be it mindfulness, happiness, or doing good deeds or what is “right.” Emptiness goes beyond these “golden chains” and is the most challenging kind of freedom. Indeed, it can be frightening.

“If we can’t go beyond this matrix of duality and our sense of being at the center of the universe, and of even the idea of being a ‘good Buddhist’ or ‘good whatever,’ I don’t see how we can be totally free. We will find comfort and even great joy, meaning, and security, but we won’t be truly happy until we let go of the matrix itself. Our reference point for letting go of the matrix in Buddhism is emptiness.”

Rinpoche also hopes that Buddhist practitioners, whether monastic or lay, can enjoy life. “I find that Buddhists can become so serious, and forget how to find magic in all the delights that life offers. We forget how to celebrate life, and become edgy or tense. We must love life in each moment. I use music—Spanish guitar—and write poems as ceremonies for myself to touch the unbelievable magic and sacredness of the world around me: my breathing, the sights around me, the colors. . . it’s all truly magical if we are in the right state of mind.”

Rinpoche also believes in the simple activities of life: looking up, breathing deeply, and setting things down and returning to nature to allow the emotions to settle. “I find going into natural environments a very soothing and calming activity. This year I took a group of people into one of the most amazing canyons—Canyon de Chelly in Arizona, on the Navajo tribal lands. We did Chod practice for six days there, with no Internet, no Wi-Fi. . . one feels like they’re on Mars or something because the canyon environment is so unique. And at night when you look up at the stars, unblocked by any light pollution, you really feel like you’re somewhere in outer space, some beautiful magical planet—it’s so amazing just to be in nature and you really feel like your mind is renewed, your person changed. It’s a kind of reprogramming. Nature is itself a spiritual teaching. Nature is Dharma, so we must make sure we have access to natural environments.”

Rinpoche is unique among other Vajrayana masters because he is willing, with non-attachment and equanimity, to discuss social problems and the divisions and tensions in our society. As he resides in the US, he is well aware of the country’s political polarization and social problems, but he simply assesses the landscape with clear eyes informed by meditation and Middle Way thought. He believes that frank discussions must be had for the sake of future generations.

“Many young people are full of fears and anxiety. We have to look at why. Young people in many developed economies, such as Hong Kong and the US, are experiencing increased fear and anxiety. In developed economies young people tend to be less religious, even in America, which is the most religious Western country.” Rinpoche laughs: “No matter how weird the religion is, at least you have a foundation of beliefs and morals to hold on to and precise guidelines for a sense of direction and life. Young people don’t have that in modern wealthy countries.”

He sees climate change as a great crisis that is contributing to young people’s state of mind. “Even if they don’t talk about it, even if they aren’t political,” he surmises, “they can really feel it in their body, that something is on the way and they don’t know how dangerous this could be. Hopefully climate change won’t end human civilization but certainly it will create havoc. Unless there is immediate intervention, I think many people will see their bubbles burst, and it won’t be business as usual. Young people feel it. Lack of direction and worries for the future are the two forces behind young people’s fear and anxiety.”

He suggests that the tools found in Buddhism—impermanence, surrender, meditation or mindfulness, and bodhisattva values—can help weather internal challenges, political instability, and even planetary disaster. It can help young people become more courageous and stronger than ever before. “Use every challenge to create benefits for oneself and others. Unleash your compassion,” he urges. “That’s what a bodhisattva does: to exploit every challenge for personal growth, spiritual awakening, and thus turn them to her advantage. If young people can be taught to meditate and to manage their emotions without too much heavy-handedness or religious doctrine, I believe Buddhist teachers will be able to help shape the next generation in a very positive direction.”

As we bid farewell to 2018 and move into the New Year of 2019, Rinpoche deeply wishes that we all meditate, regardless of spiritual belief or affiliation, and to commit to looking inward. “There are lots of wonderful teachers. And they can be regular people. That is probably the next stage of the Dharma diffusion. We don’t always need tulkus for teachers, as long as they have a good heart.”

The world is in a new period of uncertainty, and the energy of the globe is shifting unpredictably. In this context Rinpoche believes that the words “optimism” and “pessimism” are not helpful. “I wouldn’t say that we should be optimistic in the sense we try to shut off our minds and tell ourselves everything is hunky-dory. Yet too much pessimism leads to paralysis, and is an excuse for inaction. What we need is hope, an attitude of transformation and dealing with the urgent issues facing us. I’d like to have hope and faith in humanity rather than optimism.”

Wonderful article about ANAM THUBTEN ! Putting our world in perspective ❤️👍🏻🙏🏻