Le Grand Art is the fictional diary of an “actress in a rut,” completed by Alexandra David-Neel in Tunis on 6 August 1902. By then the bestselling-author-to-be was already publicly known under the stage and pen name Alexandra Myrial, under which she signed her first novel. On 11 October 1904, during a five-month stay in Europe, she wrote to her husband that she was busy with the submission of her manuscript to a couple of cutting-edge Parisian publishers. By the end of 1904, she gave up the project in order to devote herself to her writings about Asia, Buddhism, and Tibet. Yet she bore her novel in mind for a long time, since she planned to update her manuscript when she returned from Lhasa. Once again the project was abandoned.

In the process, the author proofread her text several times, made numerous corrections and annotations, and removed 164 folios from the original 802-page volume. Collecting dust over the years, the manuscript was kept closed for decades, lying dormant on a shelf in the author’s house at Digne-les-Bains in Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, southern France. During all this time, this hidden work has only been disclosed to a limited happy few biographers. On 11 October 2018, the full version of the text as David-Neel last wished to publish it was made available to all for the first time in a critical and commented edition published by Le Tripode.

Since her heroic journey to Lhasa in 1924, Alexandra David-Neel has been celebrated as a Western Buddhist icon who popularized the modern perception of Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism. The author very rarely mentioned her own past life as an opera singer during the last decade of 19th century and never ever revealed her first book-length literary endeavor in which she said farewell to her musical career for good. In doing so, she virtually took on a new public persona as she started her long-lasting literary career. Moreover she never really said goodbye to drama and theatricality, as her later fiction and nonfiction books profusely show.

In her 1927 bestseller My Journey to Lhasa, David-Neel narrates how on her way to Lhasa, at the mercy of Po-pa “brigands” near Po yul in eastern Tibet, she “found the plot of the drama to be played on that rustic stage: a “powerful tragedienne” transformed into a terrifying khandroma (mkha’ ’gro ma, a dakini), she summoned wrathful deities. Taking advantage of the awe-inspiring scenery of the lower Tsangpo valley, she created an “occult atmosphere” that petrified the Po-pa villagers with horror and made herself thrill. In this highly dramatically written scene recalling the scene of the Walpurgis Night in the fifth act of Faust, Gounod’s opera in which she had played the part of Marguerite so many times, David-Neel’s acting proficiency literally saved her and her adopted son, Lama Aphur Yongden.

Two years later, in Magic and Mystery in Tibet, she describes the Dzogchen ritual of chöd (gcod) as a “drama enacted by a single actor.” She carefully delineates the practice of the ritual as a performance that follows a kind of set libretto with the aim of creating an inner stage in the practitioner’s mind (she refers to the Tibetan notion of migs pa as an act of imagination and extreme “concentration of thought.”) David-Neel’s presentation of Tantric rituals strikingly echoes her words in a letter sent to her husband in 1915 while she was being initiated to Tantric practices in northern Sikkim: “all is empty and vain, an illusion and a mirage, and the ironic performer himself is only a shadow, a ghost devoid of reality.” Once again, this scene is important to her because it is intricately bound to the idea of illusion and to the quest of liberation. Once again, David-Neel as a writer is the one who can give her readers access to the drama happening behind the scenes.

© Ville de Digne-les-Bains

In her writings on Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism, David-Neel used to stage herself in a variety of narrative fashions, in a multiplicity of roles. Nevertheless, none of her books can be described as autobiographical accounts. In 1933, she told her friend Claire Charles-Géniaux that “nothing is more absurd than publishing one’s own private, mystical, or intellectual experiences. Still, if I were to write my biography, or if I told it under the guise of a novel, I have sometimes imagined that it could be enlightening and useful as a model of strength, will, and a result of a ceaseless concentration of thought.” In light of what we have seen, these words are striking, even more so since David-Neel did not tell Charles-Géniaux anything about Le Grand Art.

Intriguingly, David-Neel gives an important guideline for the reading of Le Grand Art written three decades before and obviously holds it as a defining feature of her attitude toward fiction in her writings without even mentioning her first literary effort. Instead, David-Neel sums up the hard core of her understanding of Buddhism, the way it pertains to her own vision of life as a modern European Buddhist: “One can live the life of a Westerner, accomplish the same deeds as other people, while being convinced of the illusory and transient nature of the self and watching as a calm and amused spectator actors playing on the theater stage of the world of appearances.”

In her Secret Oral Teachings in Tibetan Buddhist Sects, David-Neel describes this vision as the “transcendent insight” (lhag thong) leading to liberation. Such a “conviction” is the core of David-Neel’s understanding of Buddhism. From early on, David-Neel maintained that the world is an illusion. She acknowledged the fact that there is no way out of the world’s “stage.” In doing so, she reenacted a key idea of Western theatrics that, among many other instances, has been best captured in a famous line of Shakespeare’s comedy As you like it: “all the world’s a stage.” Yet David-Neel gives this inherited idea a twist in emphasizing its links with the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism. In this regard, she shifts the Western idea of theatrical illusion into a Buddhist soteriological framework, as she makes clear throughout her early writings including Le Grand Art that she believes that there is a way out of suffering. This is the issue on which Le Grand Art sheds unsuspected light: even though Buddhism is not an explicit topic here and the main character, Cécile Raynaud, in no way claims to be a Buddhist, the novel is deeply embedded in Buddhism as the latter provides the novel with a coherent philosophical background and shapes its narrative structure. As such, Le Grand Art stands out as one of the very first European literary efforts to incorporate Buddhism into modern literature.

© Ville de Digne-les-Bains

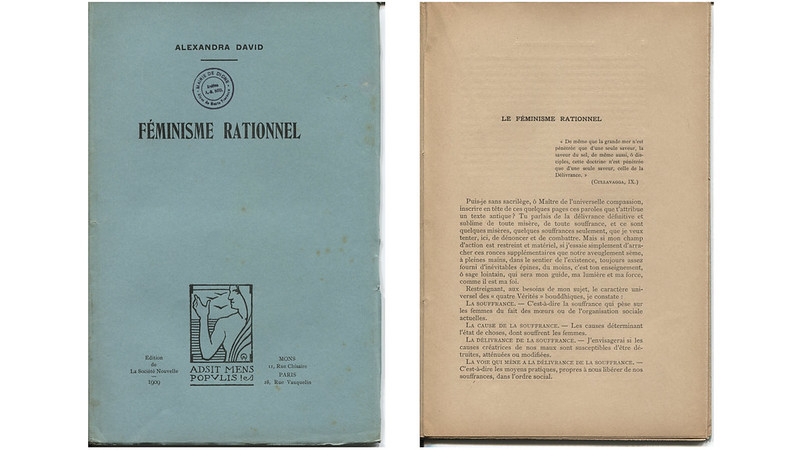

As reading the novel makes one realize, David-Neel was an eager and alert reader and made wide-ranging references to the literary culture of her time. Le Grand Art’s main achievement certainly resides in the Buddhification of the literary background of David-Neel (and her contemporaries), ranging from religious publications and philosophical works to fin de siècle novels. The author’s use of drama and her vision of literature strikingly reflect her Buddhist convictions. As David-Neel argues in other short pieces published in anarchistic and feminist venues in the same period, the Buddha’s teachings based on the recognition of suffering are strikingly modern: “Any suffering is a disorder,” she writes in 1895. She will shortly translate the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism into the language of feminism, as she senses that the Buddha’s insights straightforwardly pertain to the condition of women in particular.

© Ville de Digne-les-Bains

In applying her understanding of Buddhism as a Western Buddhist pioneer, and her own Buddhist values, to fiction, David-Neel set out from her very first book-length work on an unprecedented example of a complex and deeply embedded cultural transfer where Buddhism meets European literary and theatrical cultures. This feature is integral to the plot line of the narrative and is vital to the process of reading the book. Still, it is no spoiler to point out here that David-Neel’s fictional alter ego, the actress Cécile Raynaud, led astray on the “disenchanted trails of eternal cycles,” simultaneously explores self-reflexive writing in order to give a self-made—and woman-made—literary shape to her progressive “awakenings” along the path of existence. Eventually, this novel is a subversive act that definitely tells a compelling success story both about the impermanence of self and about self-fashioning. One clearly sees here how literature, theater, and Buddhism intricately merge into a modern response to the idea of a liberation from the “human comedy.”

At the time when David-Neel was known as an opera singer, the life story of the Buddha was becoming a key topic of a large number of plays, operas, and ballets worldwide. From 1894–96, French icon Sarah Bernhardt nicknamed “la Divine” even performed such a “Buddhadrama” in Paris, London, Montreal, Toronto, New York, and Chicago. One of the most popular “Buddhadramas” at the time, Izéÿl, as the play was called, reached a wide audience, providing the spectators with unprecedented insights into the teachings of Buddhism and creating a visual and dramatic imaginaire of the practice of Buddhism. While David-Neel was certainly aware of this trend and definitely and successfully played parts in operas reflecting European perceptions of Asian religions, her own contribution to the entangled history of Western theatrics and Buddhism does not lie in the performance of Buddhism on “real” stages.

On her return from Lhasa, David-Neel did some sort of performances with her lama “son” Aphur Yongden using Tibetan ritual paraphernalia during public talks on Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism. Yet her personal and crucial contribution lies more precisely in the transposition of performances of Buddhism in her books, usually as narratives. With her—with the distinctive narrative voice and tone of her written work—literature became a privileged medium where the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction fade, where the reader is silently and privately experiencing the entrances and exits of striking characters and the arising and disappearance of dramatic events while being provided access to the scenes through a rear entrance, since here Buddhism is best staged as an inward drama leading to one’s own truth.

© Ville de Digne-les-Bains

This makes clear why Le Grand Art is a so-far missing key to understanding the role of performing arts and literature in the advent of modern Buddhism. The novel also highlights its author not only as a feminine icon of exploration and as a Buddhist pioneer, but as a writer whose past as an actress contributed to fashion Buddhism as a spiritual performance suited to European yearnings. This also makes clear why publishing Le Grand Art only a few days before her 150th birth anniversary (she was born on 24 October 1868), should be regarded as a respectful homage to this still astonishing and awe-inspiring femme de lettres.

Samuel Thévoz holds a PhD in literary studies from the University of Lausanne and has recently been awarded a Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation/ACLS research fellowship. His research falls into three main areas: the perception of Tibet in travel literature and Western academia; the rise of modern Buddhism in art and theater; the first travels of Tibetans to France and Europe. Learn more about his work here.

See more

Maison Alexandra Davide-Neel: Samten Dzong

Le Grand Art (Le Tripode)

The Assimilation of Yogic Religions through Pop Culture