Last month, we explored self-acceptance as the ground of making resolutions for the New Year. This month, I’d like to go deeper into self-acceptance by contemplating how our reactions to others, specifically those we idolize and those we despise, reflect our capacity to accept ourselves.

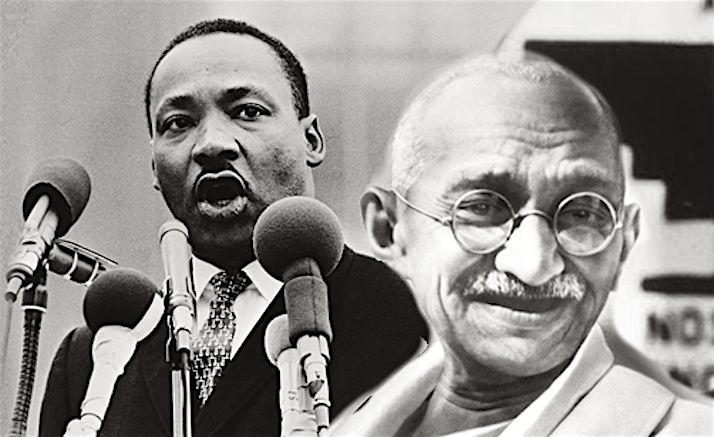

Here in the United States, we just celebrated Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. I’ve felt very joyful taking time to contemplate the message and legacy of this Nobel Peace Prize winner and martyr of the Civil Rights Movement. Just evoking his name brings up a sense of tenderness, inspiration, and awe. The more I’ve learned about his life, the more amazed I’ve been by his consistent commitment to non-violence in the face of extreme violence and systemic oppression, and the depth of his understanding of humanity.

But there are also numerous accounts of his extramarital affairs. When I first heard this, I felt my heart shrink back in disbelief, especially in light of his status as a Christian minister. Beyond feeling compassion for the suffering that his wife (Coretta Scott King) must have endured, I noticed something strange happening in my mind. It was as if the neurons in my brain were trying to figure out how to re-categorize Dr. King. He had been in my “hero” category, and adultery didn’t fit into that picture. Breathing mindfully, the discomfort invited me to look deeper into my thoughts and the habit of categorizing people in general. I remembered that I needn’t categorize Dr. King, or anyone else for that matter. It was oddly liberating to know that someone who had accomplished so much good in the world, a true hero, was still a human being with difficulties and failures—just like me and you. In fact real life heroes can be much more inspiring than air-brushed heroes without any flaws, who are therefore impossible to emulate.

There are many parallels to this story with Mahatma Gandhi, also in my “hero” category. His work and his love have brought freedom to hundreds of millions of people and continue to inspire the generations that follow, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. And, as with Dr. King, there are aspects of Gandhi’s life that don’t fit with the “hero” image. His practice of “testing” his celibacy, where he insisted that naked young women and even teenagers sleep in his bed with him, sound today more like child abuse than spiritual practice.

I bring up these lesser-known facts about these two great beings as a practice in mindfulness. They give us the chance to look more deeply into our perceptions and assumptions. Where does your mind go upon hearing about Dr. King’s infidelity and Gandhi’s “experiments”? Do you hold on to their good deeds while shutting out their harmful actions? Do you focus on their misconduct and ignore their great contributions to humanity? Can you make space for both?

Sitting in meditation with these contradictions, after a short time I was able to meet the discomfort with peace. I was not present to either King’s or Gandhi’s life and it is not my place to judge either of them. I can, however, shift my understanding of what constitutes “greatness” in a human life. It’s almost comforting to know that one does not need to be “perfect” to do great things in the world. By this, I do not mean to diminish the harm that likely arose from their misconduct. I also don’t need to diminish the capacity of my heart by categorizing anyone into being just one thing. I see that how I react to the actions of others is a mirror to how I react to my own actions. The more I judge others, the more I judge myself and no one wins.

Perhaps take a moment to reflect. How do you respond to complexity in the world? More importantly, how do you respond to complexity in yourself? Can you make space for contradiction and paradox, or do you pigeonhole yourself into being a hero or a villain? I often swing back and forth, focusing mostly on the negative and then mostly on the positive, both in myself and in the world. But when I am grounded and able to quiet my mind, there is no conflict between my skillfulness and my unskillfulness. There is merely spaciousness and acceptance, warm and inviting, with no expectations. Ultimately, I can recognize parts of myself in Gandhi and in Dr. King. There’s even a little Hitler in me, too. Did you know that Hitler applied twice to Art School and was rejected both times? And that he lost both of his parents before he turned 20? I, too, am a creative person, have been rejected, and have lost both of my parents. I hope never to commit the atrocities that Hitler did, but when I look deeply I can see that there is a little of Hitler in me, too. Everyone has the capacity for destruction, as well as for liberation.

So here’s the strange secret—when we can see the fullness of our humanity, not getting stuck in a pigeonholed image of anyone, then we’re already practicing acceptance. We’ve stepped outside of dualistic thinking and entered into the stream of awakening, even if only for a moment. Hence the Heart Sutra’s famous line, “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form.” It may sound like an infuriating riddle, but really it’s an invitation to freedom—the freedom from having to squish the complexity of reality into categories of right and wrong. It’s such a different way of thinking that it may seem foreign, but it’s as intimate and as accessible as one mindful breath.

This contemplation is about more than famous figures of the 20th century. It can be applied to movie stars, politicians, our neighbors, and certainly our families. Do we get caught in judgement as we try to compartmentalize them, labeling them as “good” or “bad”? And are we doing the same thing to ourselves? Do we deny the reality of our humanity, or can we make space for the inconsistent nature of all of life? Experiencing the pain that comes from labeling people and thus closing the heart, it’s become clear for me that living with an open heart, in touch with reality, is the only path to personal and collective healing, peace, and joy.

I come back to Dr. King in order to reflect on forgiveness, which is a natural outcome of an open and accepting heart. From his sermon entitled “Loving one’s Enemies”:

“Forgiveness does not mean ignoring what has been done or putting a false label on an evil act. It means, rather, that the evil act no longer remains as a barrier to the relationship. Forgiveness is a catalyst creating the atmosphere necessary for a fresh start and a new beginning. It is the lifting of a burden or the canceling of a debt. The words ‘I will forgive you, but I’ll never forget what you’ve done’ never explain the real nature of forgiveness. Certainly one can never forget, if that means erasing it totally from his mind. But when we forgive, we forget in the sense that the evil deed is no longer a mental block impeding a new relationship. Likewise, we can never say, ‘I will forgive you, but I won’t have anything further to do with you.’ Forgiveness means reconciliation, a coming together again. Without this, no man can love his enemies. The degree to which we are able to forgive determines the degree to which we are able to love our enemies” (King 2015, 69).

I don’t know how this applied to Dr. King’s marriage, but there is clearly truth to this statement. I would have to add that the degree to which we are able to accept and forgive anyone determines the degree to which we are able to accept and love ourselves. And the whole world.

* King, Martin Luther. 2015. The Radical King. Edited by Cornell West. Boston: Beacon Press.