The enlightened mind is a revolutionary mind. A revolutionary mind aspires to develop the minds of others out of great compassion, unbound by time or place. The historical Buddha began his revolution within himself and then moved his focus outward toward the world, thus making him samyaksambuddha, manifesting the “perfect enlightenment” of universal buddhahood.

In the eighth week following the awakening, the newly enlightened Buddha was seated under the Bodhi tree at Uruvela on the bank of the Niranjana River. He was alone and in seclusion, in full peace and harmony. During this time, this line of thinking arose in his awareness: “This Dhamma that I have attained is deep and intense, hard to see, hard to realize, peaceful, refined, beyond the scope of conjecture, thoroughly investigated, subtle, to be experienced by the wise. But this generation delights in attachment, is excited by attachment, craves for attachment, and enjoys attachment. For a generation delighting in attachment, excited by attachment, craving for attachment, enjoying attachment, this/that conditionality and dependent co-arising are hard to see. This state, too, is hard to see: the resolution of all fabrications, the relinquishment of all acquisitions, the ending of craving; dispassion; cessation; unbinding. And if I were to teach the Dhamma and if others would not understand me, that would be tiresome for me, troublesome for me.” Therefore, the Buddha hesitated to teach the Dhamma, apprehensive that it would be too profound for human comprehension.

Understanding Buddhism is more difficult than believing in a god or professing blind faith. Believing in a god or supernatural power is the easiest thing to do as you simply put the whole responsibility of transforming the self and society upon God. There is no spiritual endeavor or effort required except for ceremonies, whereas Buddhism is all about endeavor and effort and hardship, which many of us are not yet ready to undertake. However, practicing Buddhists can enjoy the fruits of their practice and keep moving forward, which gives them happiness at different levels of their practice.

Buddhism is a spiritual path, which is another term for “skillful actions.” Buddhist practices, especially meditation, are popularly associated with happiness, contentment, and well-being. To distracted, dissatisfied, and overworked people, being a Buddhist is the most sensible and practical lifestyle choice. However, developing confidence and making efforts are essential for practicing Buddhism, otherwise it becomes extremely difficult.

After the seven weeks of enlightenment, the Buddha’s mind was inclined to dwell at ease with calmness, rather than teaching the Dhamma, seeing the challenges that people faced in society. Then Brahma Sahampati, having known with his own awareness the line of thinking in the Blessed One’s awareness, thought: “The world is lost! The world is destroyed! The mind of the Tathagata, the Arahant, the Rightly Self-awakened One inclines to dwell at ease, not to teaching the Dhamma!” Then, just as a strong man might extend his flexed arm or flex his extended arm, Brahma Sahampati disappeared from the Brahma-world and reappeared in front of the Blessed One. Arranging his upper robe over one shoulder, he knelt with his right knee on the ground, saluted the Blessed One with his hands before his heart, and said to him: “Lord, let the Blessed One teach the Dhamma! Let the One-Well-Gone teach the Dhamma! There are beings with little dust in their eyes who are falling away because they do not hear the Dhamma. There will be those who will understand the Dhamma.”

Khmer depiction of Brahma, Koh Ker style,

housed at the Guimet Museum in Paris.

Image courtesy of the author

Brahma Sahampati then became aware of what was going on in the Buddha’s mind. Distressed at the Buddha’s hesitancy, he thought: “The world will be lost, utterly perish since the mind of the Tathagata, the Arahant, the Supreme Buddha inclines to inaction and not toward preaching the Dhamma!” So he appeared before the Buddha, respectfully stooped with his right knee to the ground, paid homage, and appealed to him to teach:

“Let the Exalted One preach the Dhamma! There are beings with little dust in their eyes; they are wasting from not hearing the Dhamma. There will be those who will understand the Dhamma.”

(MN 26.20)

The Buddha then gazed out upon the world with his “eye of a buddha,” and having seen that there are beings “with little dust in their eyes” who would be capable of understanding the truth, he announced: “Open for them are the doors to the Deathless”—a gift that has come down to us through the centuries. Brahma Sahampati was gratified and joyously thought, “Now I am one who has given an opening for the Buddha to teach the Dhamma to beings.” The Brahma Sahampati then bowed to the Buddha and vanished.

One might wonder why the Buddha, who had prepared himself for numerous lifetimes just to teach the Dhamma to other beings, needed the prompting of Brahma Sahampati to set out on his mission. At the same time, one should not become carried away by the notion that Brahma as referred to in Hinduism is the same as referred to in Buddhism, which would destroy the very fundamental teachings of Buddhism. In Hindu literature, one of the earliest mentions of the deity Brahma, with Vishnu and Shiva, is in the Fifth Prapathaka (Skt. lesson) of the Maitrayaniya Upanishad, probably composed in the late first millennium BCE, after the rise of Buddhism. Buddhism uses the term “Brahma” to deny a creator, as well as to delegate him as less important than the Buddha, while explaining the four stages of enlightenment.

Early Buddhists rejected the Hindu concept of Brahma, and thereby polemically challenged the Vedic and Upanishadic concept of an abstract, metaphysical Brahman. This critique of Brahma in early Buddhist texts was aimed at ridiculing the Vedas. But at the same time, Buddhism simultaneously calls metta (Pali. loving-kindness, compassion) as the state of union with Brahma. The early Buddhist approach to Brahma was to reject any creator aspect, while retaining the brahmavihara aspects of Brahma, in the Buddhist value system.

The word Brahma is normally used in Buddhist suttas to mean “best,” or “supreme.” Brahma in the context of Brahma Sahampati means a leading god (deva) and a heavenly king in Buddhism. He is considered a protector of teachings (dharmapala), and is never depicted in early Buddhist texts as a creator god. In the Buddhist tradition, it was the deity Brahma Sahampati who appeared before the Buddha and urged him to teach, once the Buddha had attained enlightenment but was yet unsure if he should share his insights with anyone.

Brahma Sahampati plays a key dramatic role in the Buddha’s life. According to the Ayacana Sutta, he takes the initiative to invite the Buddha to declare his awakening to the world. However, Brahma Sahampati is not a heavenly figure but one closely connected with the dispensation of the Buddha’s mind of overflowing compassion. Brahma Sahampati means “Supreme Lord of a Thousand Worlds,” which is to say the greatest being of the world who resides in anagami; the non-returner who is the third stage of enlightenment. The Brahma statue at the famous Erawan Shrine in Bangkok represents four aspects of life, namely: livelihood and life, relationship and family, wealth, and wisdom and health.

Therefore, the parable of Brahma Sahampati is a thought that emerges out of the Buddha’s mind to decide upon imparting the teaching to others, out of great compassion toward human beings. The Buddha did not need to be reminded by someone else of his own responsibilities. The Buddha has the quality of great compassion and supreme wisdom, with an inexhaustible energy and unperturbed creativity.

Another famous Buddhist parable is the Lotus Parable. Just as some lotus flowers, born and growing in water, might flourish while immersed in the water, some may remain without rising up from the water, some might stand at an even level with the surface of the water, while some others might rise up from the water and stand without being submerged in the water, and so on. The Buddha saw the whole world with the eye of an Awakened One. He saw beings with little dust in their eyes and those with much; those with keen faculties and those with dull; those with good attributes and those with bad; those easy to teach and those difficult; some of them seeing disgrace and danger in the world. Based on this vision, the Buddha answered to himself (Brahma Sahampati): “Opened for those who hear are the doors of the Deathless, Brahma, let them give forth their faith; thinking of useless fatigue, Brahma, I have not preached the Dhamma Sublime and excellent for men.”

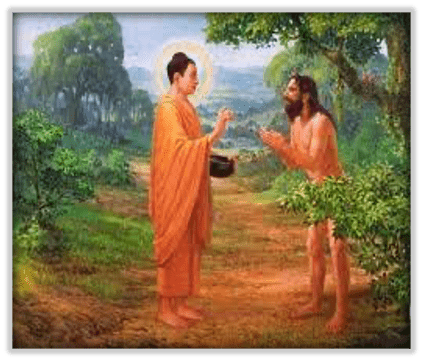

Then Brahma Sahampati, thinking, “The Blessed One has given his consent to teach the Dhamma,” bowed to the Blessed One and, circling him on the right, disappeared. This implies that the thought vanished from the Buddha’s mind completely as the Buddha decided to teach the Dhamma to others. Thus, the Buddha decided to teach his insights to his former teachers, Alara Kalama and Udaka Ramaputta, but they had already died, so he decided to visit his five former companions who were living in Isipatana. On his way, the Buddha encountered an Ajivaka practitioner named Upaka. The Buddha proclaimed that he had attained full awakening, but Upaka was not immediately convinced and said: “It may be so, friend,” and took a different path. We need to be reminded at this point that not even for one who has achieved supreme enlightenment does everything suddenly go according to the way one would wish. In the case of Upaka, there is a lack of receptiveness and interest to investigate.

The Buddha then journeyed from Bodh Gaya to Sarnath, a small town near the sacred city of Varanasi in central India. There he met his five former companions, the ascetics with whom he had shared six years of hardship. Thereupon the Buddha gave the teaching that was later recorded as the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, which introduces fundamental concepts of Buddhist thought, such as the Middle Way and the Four Noble Truths. This is why we call the Buddha samyaksambuddha.

At least some of the early Buddhist schools used the concept of three vehicles:

1. Sravakayana

2. Pratyekabuddhayana

3. Bodhisattvayana

Sravakayana is the path that meets the goals of an arhat—an individual who attains liberation as a result of listening to the teachings (or following a lineage) of a samyaksambuddha. A buddha who attains enlightenment through Sravakayanais called a sravakabuddha, as distinguished from a samyaksambuddha (Skt., Pali: sammasambuddha) or pratyekabuddha (Skt., Pali: paccekabuddha).

Savaka means “one who hears;” a person who follows the path to enlightenment by means of hearing the instructions of others. Laypeople who take special vows are called savakas. Such enlightened disciples attain nibbaṇa by hearing the Dhamma as initially taught by a sammasambuddha. A savakabuddha is distinguished from a sammasambuddha and a paccekabuddha. The standard designation for such a person is an arhat.

Pratyekabuddhas are said to attain enlightenment on their own, without the use of teachers or guides, according to some traditions by seeing and understanding dependent origination. According to the Theravada school, paccekabuddhas (one who has attained supreme and perfect insight, but who dies without proclaiming the truth to the world) are unable to teach the Dhamma, which requires the omniscience and supreme compassion of a sammasambuddha, who may even hesitate to attempt to teach.

Samyaksambuddhas or sammasambuddhas rediscover the truths and the path to awakening and teach these to others after their awakening. This is why, among all other buddhas, we pay homage to the historical Buddha, formerly Siddhartha Gautama. Bodhisattvayana also refers to the path of the bodhisattva striving to become a fully awakened buddha (samyaksambuddha), for the benefit of all sentient beings, and is thus also called the Bodhisattva Vehicle. Mahayana Buddhism generally sees the goal of becoming a buddha through the bodhisattva path as being available to all and sees the state of the arhat as incomplete.

According to the Pali Canon, a Brahmin visited the Buddha who was seated under the Ajapala Nigrodha tree during the fifth week after his enlightenment. The Brahmin asked questions regarding the nature of true brahmin. The Buddha explained them but it made no impression on the Brahmin. The fifth century commentator and philosopher Buddhaghosa explained that the Brahmin was filled with haughtiness and wrath, and went about uttering the sound “hu-hum” which later became his name Huhunkajatika Brahmin. Even though the Brahmin was not interested in the Buddha’s teachings, the Buddha had great compassion for this Brahmin as he could see his arrogance.

During the seventh week after enlightenment, two merchants, Tapassu and Bhallika, who traveled to different parts, met the Buddha who was seated under the Rajayatana tree. They offered the first meritorious alms to the Buddha, took refuge in the Buddha and the Dhamma, became the first lay disciples to the Buddha, and availed the first hair relic of the Buddha as an object of worship. These hair relics, called Kesa Datu, were later reputed to be enshrined by the merchants on their return home to what is now known as Burma, in Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon (Rangoon). Certainly, the Buddha’s inner voice could have been stimulated out of compassion for all beings based on the Brahmin’s ignorance and the two merchants’ gratitude. In each of these cases, the Buddha was being approached by these four men out of curiosity. However, above all these historic events, the Buddha approaching his former five companions and imparting the teaching of His Dhamma is considered to be the most important as it manifests the Great Compassion of the Buddha for all sentient beings.

The Pali literature of the Theravada tradition includes tales of 29 buddhas. The Buddhavamsa is a text that describes the life of Shakyamuni Buddha and the 27 buddhas who preceded him, along with the future Metteyya Buddha (Skt: Maitreya). None of the 27 buddhas were considered to be samyaksambuddhas. The Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, the setting in motion of the Wheel of the Dhamma is considered to be a record of the first sermon given by the Buddha. The Dhammacakka or Wheel of Dhamma, is a Buddhist symbol referring to the Buddha’s teaching of the path to enlightenment. Pavattana can be translated as “turning” or “rolling” or “setting in motion.”

Hence, the thought of Brahma Sahampati transforming the Buddha from a paccekabuddha to a sammasambuddha with great compassion for liberating all beings came from the Buddha himself. Hence the Buddhist chant “Namo Tassa Bhagavato Arahato Sammasambuddhassa” before reciting suttas or beginning meditation. The Buddha never remained indifferent. In this way, the Buddha’s revolution in both thought and action forever changed not only the Indian society but also the world.

References

Subhuti. 2009,The Buddha’s Enlightenment – Seven Weeks of Enlightenment.

Sangharakshita. 1972. The New Man Speaks.

Sangharakshita. 2004. The Guide to the Buddhist Path. Cambridge: Windhorse Publications.

Ambedkar, Dr. B. R. 1957. The Buddha and His Dhamma. Mumbai: Siddhartha College Publications.

Horner, I. B. 1967. Majjhima Nikaya I (Middle Length Sayings), Ariyapariyesana Sutta. Oxford: The Pali Text Society.

Kalupahana, David. 1975. Causality: The Central Philosophy of Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press

Obeyesekere, Gananath. 2006. Karma and Rebirth: A Cross Cultural Study. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House.

Snelling, John. 1987, The Buddhist Handbook. A Complete Guide to Buddhist Teaching and Practice. London: Century.

Gyaltsen Rinpoche, Khenpo Konchog. 1998. Jewel Ornament of Liberation. New York: Snow Lion Publications.

Nakamura, Hajime. 2007, Indian Buddhism: A Survey With Bibliography Notes. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House.

Kloppenborg, Ria. 1974. The Paccekabuddha: A Buddhist Ascetic. Leiden: Brill Archive.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu. Ayacana Sutta: The Request (SN 6.1) translated from the

Pali.

Warder, A. K. 1970. The Mahayana, ‘Great Vehicle’ or ‘Great Carriage’ (for carrying all beings to nirvana), is also, and perhaps more correctly and accurately, known as the Bodhisattvayana, the bodhisattva’s vehicle.

Williams, Paul. 1989, Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. Psychology Press.

W. Rahula. 1996. Theravada – Mahayana Buddhism; in: “Gems of Buddhist

Wisdom”.

Keown, Damien (. 2003), . A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Related features from BDG

How I Became a Theravada Buddhist

Book Review: Esoteric Theravada: The Story of the Forgotten Meditation Tradition of Southeast Asia

Changing Perceptions: Reflections on the View of Theravada as the “Lesser Vehicle”