In the US, where I’m from, the words “healthcare” and “healing” carry very specific impressions: white-coated doctors, antiseptic rooms, pharmaceuticals . . . and fear. I would much rather be part of a world that finds health though meditation, intentional positive thought, and beauty. I think that the best way I can do this in my own life is through my spiritual practice and by painting thangkas (painted or embroidered depictions of a deity, scene, or mandala from Tibetan Buddhism), which I’ve done since 2001. My current focus is a thangka of the Vajrayana Buddhist healing practice called the Chöd Pacification of Suffering.

According to my understanding of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, poor health is caused by mischievous, malevolent spirits. In the West we take a “going-to-war” approach by attempting to eliminate the symptoms of ill health, but Chöd teaches us to contact these spirits and ask them politely to leave, with a gift of our own life force that is love. This allows the sufferer’s vital forces to heal the chaos wrought by the spirits.

For several years I’ve wanted to create a large, detailed painting of the entire Chöd practice in a traditional thangka style, but for a Western audience. While Chöd thangkas exist, the ones I’ve seen are created with people of Himalayan heritage in mind. Discussing my project with my Tibetan Chöd teacher, Lama Tsering Wangdu Rimpoche, I realized that it could be a service to the Western Chöd community. Those exchanges showed me that people from Rimpoche’s part of the world tend to have an innate knowledge of Tibetan and Buddhist culture such that many details can be omitted from the Chöd paintings and they will still understand the context and imagery.

When I was initiated in the Nyingma tantric order of Buddhism in 2001, I found the Chöd visualizations complex and unusual, coming from a different cultural mindset. As I persisted, the visualizations took on a life of their own and became beautiful and powerful to me—so much so that they could fill me with awe or overwhelming feelings of love. I think it is easy for Westerners to become caught up in some of the unusual imagery—what, skullcups full of blood? Yeck!—and to be impatient for the practice to take root and unfold, and I believe that this painting can help with this. Prints will be on sale as part of an outreach to the local community and the world at large by The Movement Center in Portland, Oregon, which teaches Chöd to the public on a regular basis.

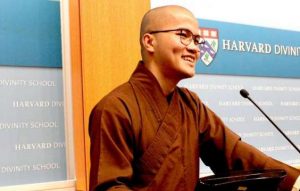

My root guru, Swami Chetanananda, is an American meditation master who became a renunciate in the Saraswati order in 1978. At The Movement Center, he teaches a fusion of Kashmir Shaivite meditation and various Buddhist practices, the lineages of which were transmitted to him by Lama Tsering Wangdu Rimpoche, an abbot of the Pal Gyi Langkor Jangsem Kunga Ling Monastery in Boudha, Nepal. Both the Nyingma and Kashmir Shaivite schools are tantric, and they share many similarities. While it is unusual for one Dharma center to have two lineages, we are fortunate to have both styles to draw from in the quest for spiritual growth.

I began work on this painting in June 2014. My goal is to create a large (56” x 45”), beautiful, detailed piece of art to captivate the imaginations of people who are learning the practice and visualization. I think that complexity and beauty are the qualities that open people’s hearts and minds when they view my art, so I want them to be prominent features. I began by deciding how to express a linear storyline portraying many events simultaneously, while maintaining the aesthetic of a traditional thangka. Swami Chetanananda suggested a four-tier piece, which gave me a basic structure. From there I expanded my research by reading practice manuals and initiation transcriptions, and by asking Rimpoche.

Allow me to take you on a “tour” of the painting: a practitioner (bottom right) leaves his monastery at night to visit a cemetery to practice Chöd, which is traditionally done at a place where there is confusion or tension, or where the veil between this world and the next is thin. He walks along, reciting the mantra for the practice and visualizing the area in which he’s going to do it. Next, we see him seated in the center of the bottom register, in a forest glen at night. Circling him is a fence of dorje (a ritual object representing the “thunderbolt” of enlightenment) and a wall of flames that he has envisioned to make the space sacred and safe to perform the practice. Illness-causing demons and energies representing the five directions surround him. The lord and lady of the cremation ground rise out of the ground and dance around the practitioner.

Behind and above is the practitioner’s visualized offering—his own body on top of Mount Meru. Above dances Troma Nagmo, the main deity of the practice, vast as space, arisen from his mind. She is fierce, on fire with the intensity of her compassion for all beings, which burns through the fabric of duality, the illusion of this and that, right and wrong, God separate from me. She is surrounded by the cosmos, strewn with more offerings that the practitioner envisions, mounds of flesh and blood and bones, money, material things, whatever it is that the illness-causing demons want, more than they can ever need. A large skullcup floats above the practitioner. In it, he visualizes placing his body in offering to the demons, his teachers, the gods of the place, passersby, and all enlightened beings. His simple offering transforms into the most desirable elixir called amrita by the fire of his commitment to the practice, represented by flames below the skullcup, and by the wish to give. Around Troma Nagmo is the lineage field of The Movement Center, both the Buddhist and Kashmir Shaivite sides. Sitting at their feet are students and all humanity. Higher on the canvas, the sky becomes lighter and iridescently luminous. Small dakinis (manifestations of enlightened energy) fly through the air, bringing copper cups of the amrita offering to the deities, teachers, people, and spirits above.

Above the lineage field are the Buddhas representing the five Buddha families, and to their sides are the yidams—the protective deities for those who practice Chöd: Marchungma, White Mahakala, Palden Lhamo, Green Tara, and Avalokiteshvara. Above Troma is Vajravarahi, her outer form, representing the energy and vitality of life itself, and at the top is Prajnaparamita, the primordial goddess who personifies the potency of space, scintillating stillness, potent awareness. She is the first deity acknowledged when the practice starts. Around her are the bodhisattvas Vajrasattva, Samantabhadra, and Vajradhara. By giving of himself, the practitioner pacifies and satisfies the dark forces, who leave, satiated with the gifts.

Before I paint a deity, I look at many existing images to get a feeling for the underlying theme and the energies the artists are portraying. For instance, a fierce deity can have eyes that burn with intensity, but the image shouldn’t reflect a closed heart or a mean spirit—these deities aren’t angry, simply on fire, often because of their passion for realization and helping beings. There are many variations in deity imagery due to political and cultural factors and different monastic traditions. I pull from a variety of styles and painting traditions—whatever inspires me—as I enjoy a variety of thangka styles and don’t cleave to the notion that one is more divinely inspired than another. Since thangka painting has traditionally celebrated the amalgamation of cultures and ages, being a mix of Indian, Nepalese, and Tibetan influences from the 10th century onwards, why stop now?

For this thangka I compiled files of images for use as inspiration, and I envisioned what the painting would look like in my visualization practice. I draw on sheets of Mylar, as it stands up to a lot of wear. I cut and reposition, I photocopy if an element I’ve drawn is the wrong size, and eventually I have a full drawing to trace onto canvas. I work on canvas prepared using hide glue and calcium carbonate on cotton because the surface feels wonderful to work on and takes the paints well. I draw the border, which helps focus my mind and prepares the field for the deities, and then paint the penciled lines. This helps me further refine my line-work and placement.

For color I use a mixture of gouache—a coarser grind of the same materials that watercolors are made from—mineral paints, and gold. Mineral paints are opaque and have rich, complex colors. Gouache is a chalky, dense, matt medium and can be used to create nuances of color such as one sees in old thangkas where there is fading and erosion of the surface, which I find beautiful. I don’t artificially age my thangkas, but I do try to create surface color such as the old thangkas have. The final touch is the addition of real gold. There is nothing like it for beauty. Gold and minerals have an energetic “umph” that make thangka paintings a very rich viewing experience compared with a painting made with synthetics. I love the reactions of people viewing my art, especially if they are seeing a thangka for the first time. I believe that art is a great tool for opening minds and hearts to different ways of living and the creative spirit of God. Art is powerful—as powerful as an inspiring lecture, a heartbreakingly beautiful sunrise, or a nourishing meal after a fast, and when my art achieves this I feel very satisfied.

Laura Santi is a traditional Buddhist thangka and Hindu deity painter and a member of the Dakini As Art Collective. To learn more about Laura, her work, and Dakini As Art, please visit Dakini As Art.

See more

Lama Tsering Wangdu Rinpoche (lamawangdu.org)

The Movement Center (themovementcenter.com)

Swami Chetanananda (chetanananda.org)

“Dakini As Art”: The Buddhist Feminine in Art (Buddhistdoor Global)