I recently attended a conference on sustainability in Nepal. Once the conference had ended, the networking activities had come to a grinding halt, and reports on Nepalese economics were filed, I decided to visit a school for Himalayan children.

Shree Mangal Dvip (SMD) boarding school lies just a stone’s throw from Boudhanath Stupa, a revered Tibetan Buddhist spiritual site in Nepal’s storied capital of Kathmandu. The school, which had just celebrated its 30th anniversary, houses nearly 500 children from parts of Nepal bordering Tibet.

I spoke with Shirley Blair, the school’s director. A petite Canadian national in her seventies, Blair is a bundle of infectious energy who has been working tirelessly as the school’s “head Sherpa” for the past two decades. Blair single-handedly shepherded the school through tumultuous years in Nepal’s history into a well-run and caring institute of learning for Himalayan children. She introduced me to the school’s principal, Acharya Tenzing Wangchuk, who assumed the role two years ago.

The children come from as far afield as as Manang, Mustang, Dolpo, and Nubri—places so remote that it often takes days, if not weeks, to reach them by car and, often for the bigger part of the journey, on foot.

“The first bunch of kids came from Nubri, and then from Manang, and all through the Himalayas,” Blair explains.

The school’s founder, Thrangu Rinpoche, 84—a highly revered scholar of Tibetan Buddhism—has educated many nuns and monks from the region in his monasteries over the years, Blair explains. While the monastics have gone on to great success as teachers and mentors in Rinpoche’s centers around the world, he also wanted to provide children with a modern education.

It is with this mission that he founded the school in Kathmandu exactly three decades ago. Since its inception, the school has provided an education for thousands of students. Many are in the final stages of finishing their formal education (university of college), while others have returned to serve their communities. The demand for education is such that the school is operating at near capacity. “We are so crowded that we can only teach up to grade 10,” says Blair. “If the students want to finish school, we have to keep them [house them at the school].

After finishing 10th grade (aged 15–16), the students volunteer in different schools, nunneries, and monasteries for a year, before continuing their higher education. Some of them go on to private schools, while others attend boarding schools abroad through partnerships that Blair has secured over the years.

To cope with overcapacity, Blair is looking to expand and possibly even build a new school outside the Kathmandu Valley, or to buy a school in Nepal, or even in India. In the meantime, she is busy helping existing students chart their future path. And she has her work cut out for her; there are, for instance, visa issues. One of her students was admitted to the Royal Academy of Hong Kong on a full scholarship, but the Hong Kong government would not issue her a visa because they do not issue visas for children to finish high school.

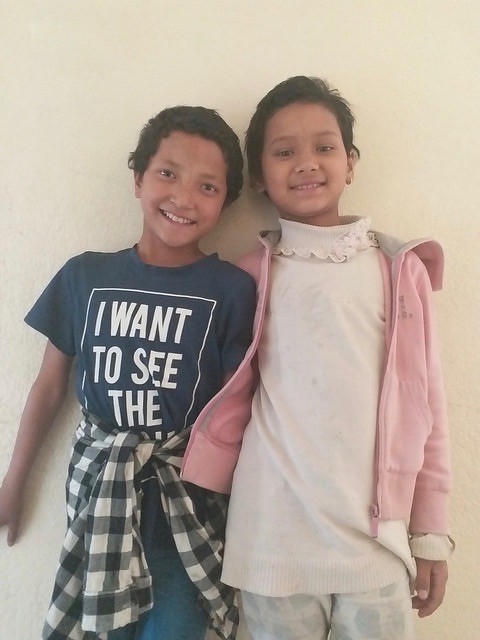

After our meeting, Blair took me upstairs to the school’s library, where one of the senior students was about to give a presentation attended by a dozen fellow students. Introductions revealed that the students had varied interests. Some of them wanted to become computer engineers, several of them doctors, one wanted to study literature, and a few of them were undecided.

The subject of the presentation was: “Why We All Must Become Vegetarians!” A young boy of Sherpa stock presented a stirring case in favor of vegetarianism. Of the many points the student marshalled against meat-eating, one was that ingesting flesh was a “sinful” act. Blair immediately corrected the boy. The idea of sin is a Christian concept, she maintained, and in Buddhism, eating meat would perhaps be described as “not skillful.” Two foreign volunteer instructors participated enthusiastically in the discussion that followed, one underscoring the importance of teaching the children critical thinking skills.

The school is somewhat unique in that it adopts an essentially Buddhist approach to education. The curriculum includes meditation, which Blair herself teaches at times. The school caters to members of both lay and monastic communities. Young monks and nuns from Thrangu Rinpoche’s monastery and nunnery in Kathmandu also attend classes as day students.

When I returned to the school two days later, it was lunch time. Principal Wangchuk had just finished his lunch and offered me a meal of dal and vegetable curry. “We never compromise on food quality, however challenging our finances,” he said, with quiet confidence.

Monthly expenses for SMD stand at about 3.8 million Nepalese rupees (roughly US$38,000). The school is fully funded by donors, with funds raised through Rinpoche’s charities registered in Canada, Hong Kong, and the US.

Wangchuk has a busy schedule, juggling his duties as a Tibetan-language teacher while dealing with requests from staff and students in need of his attention, but he set aside the time to chat with me.

After lunch, I had a chance to meet two more student instructors, one of whom had just returned from completing high school at UWC ISAK Japan. She is passionate about pursuing a career in teaching and has already been accepted by three Canadian universities for her continued education. The instructor had finished her schooling at an international school in Zurich and is hoping to pursue a career in hospitality and tourism.

Each of them relayed their experiences coping with the pressures of studying at foreign schools, and how they could implement and incorporate some of the things they had learned abroad at their alma mater.

On the whole, community service lies at the heart of the school’s mission. Rinpoche, the school’s founder, wanted them to return and serve their respective communities, most notably in healthcare. “Rinpoche’s wish is that they come back and work in the community rather than becoming lost souls in foreign countries,” Wanghcuk told me.

This lesson seems to have a universal relevance, for this skillful and sustainable approach to education is relevant not just for the Buddhist children of the Himalayas, but for anyone ambitious enough to think of ways of contributing meaningfully toward their own community.

See more