The theme of the 2017 ACLS Robert Ho Fellowship Symposium, held at the University of Toronto, was “Bridging Divides.” In thinking of how to present my own research, which aims to bring together the study of the Mongolian and Tibetan Buddhist traditions, I remembered my own journey on the academic path.

I can recall the content of the first lecture I attended at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London as an undergraduate fresher of the Study of Religions as if it were yesterday. The topic was “The Insider and Outsider Problem in the Study of Religions,”which explored the challenges met by those “outsiders” who are attempting to academically study and analyze the “insiders” of a particular religious system and its adherents. During the course of the three-hour lecture, the insider and outsider within my own psyche came into self-realization for the first time.

I was born into and brought up in a tradition-oriented Mongolian family in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China, where I began my first experience of Buddhism as an insider. Both of my parents were devout Buddhists with a deep understanding of the doctrinal aspects of the religion as a result of having elderly lamas living with their families during their childhood. They weaved the teachings of Buddhism into my upbringing, which was filled with Jataka stories and Buddhist legends containing invaluable ethical anecdotes, all of which had a hand in shaping my own identity.

Both of my parents were academics who emphasized the importance of learning as a pathway out of the difficult situation minorities such as Mongolians face in China. For this reason, my parents aspired to move our family to the West so that my brother and I could receive a better education. Language played a big part of this education from very early on, and by age four I was juggling English and Chinese alongside my Mongolian mother tongue. As a result, I have always appreciated that to fully understand and empathize with other cultures requires a thorough knowledge of their languages.

It was precisely the academic path that enabled my family to move to Cambridge, England, in 1999 to accompany my father who had started a PhD program in social anthropology at King’s College at the University of Cambridge. From then on, we became a different kind of outsider.

Throughout my life, the one thing to which I always felt like an insider was Buddhism. Regardless of tradition, cultural background, or age, Buddhism has always provided a shared platform on which I could interact with people who shared in similar views and sympathies on an academic or personal level. Consequently, the study of Buddhism as an academic career represented a path that would enable me to bridge the gap between insider and outsider and also to widen my own horizons.

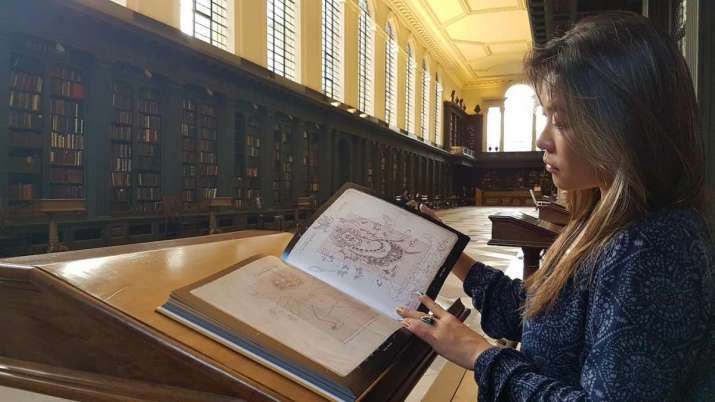

Since starting my postgraduate research at the Institute of Oriental Studies, at the University of Oxford, I have been working on a particular project that aims to bridge another gap in Buddhist studies: that between the study of Buddhism in Mongolia and in Tibet.

Tibet and Mongolia share in the same root of Buddhism—the form mainly associated with the Gelugpa tradition otherwise known as the Yellow Hat school of Tibetan Buddhism. This particular tradition has prevailed as one of the most important traditions since the enthronement of the Fifth Dalai Lama as the secular and religious ruler of Tibet in 1642. After his enthronement, the Gelugpas started to have an even greater impact among the Mongols, who had become powerful patrons of this tradition. My research focuses on this period of Tibetan Buddhism and attempts to shed light on the era by looking at works composed in Tibetan by Mongolian monk-scholars.

To date, the study of Tibetan Buddhism has been predominantly based on texts composed by Tibetans. The hundreds of volumes of Buddhist works in the Tibetan language left behind by Mongolians have barely been touched upon. Given that most Mongolian monk-scholars that we are aware of to date were from noble ancestry of the bloodline of Chinggis Khaan, they received the most exemplary education when they went to study in Tibet. Thus, it can be supposed that only the most exemplary of Mongolian monk-scholars made it to Tibet and were the ones responsible for the Tibetan-language compositions by Mongolians.

My research aims to remedy the lack of scholarship on works composed by Mongolian monk-scholars, which represent an untapped goldmine for the study of Tibetan Buddhism from at least the 16th century onwards.

The individual whose works I have been focusing on is Dza-ya Pandita Blo-bzang ‘phrin-las (1642–1715) of the Khalkha Mongols, who was recognized as an incarnation of a Chinggisid prince. He was one of the most cosmopolitan figures of his times: spending 19 years in Tibet, 11 in Qing/Southern Mongolia regions, and the rest in his motherland: the Khalkha regions. Unlike many of his peers, who held diplomatic or political roles, Dza-ya Pandita chose to dedicate his life to spreading the Buddhist teachings. He was representative of a truly cosmopolitan and well-traveled individual of his times.

His masterpiece is known as the Clear Mirror of Records of Teachings Received. It belongs to a genre of Tibetan Buddhist literature known as thob yig that, like many other Tibetan works, often contains characteristics bridging other genres such as bibliographical, biographical, autobiographical, historiographical, encyclopedic, chronological, and so on. It is the second-largest example of its genre spanning 1,234 folios and has never before been studied in detail.

Given the fluidity of genre in Tibetan Buddhist literature, the context is important for understanding the text and its purposes. This particular text was composed as part of the author’s aspiration to spread Buddhism in Mongolia. From looking at the contents, the element which makes this text a truly unique example of its genre is the huge number of biographies, totaling at least 227, which form its structural backbone. A deeper analysis of these biographies suggest that it is precisely through these life stories that Dza-ya Pandita made his biggest attempt to spread Buddhism in Mongolia.

In general, thob yig simply documents transmission lineages of texts and practices. By writing a work that contains numerous extensive life stories reaching far back into the past, Dza-ya Paṇḍita was able to compose a work that covers not only transmission lineages but also ancestral lineages, master-disciple lineages, and reincarnation lineages. The life stories he wrote brought the exemplary lives of past masters closer to his own times, and thus provided role models for his disciples. In doing so, he was able to give life to the tradition and its accompanying teachings and practices, which he himself was responsible for spreading in Mongolia.

Dza-ya Pandita was concerned with presenting his work structurally and stylistically in an authentic “Tibetan Buddhist” way, which mirrors his aspiration to spread a form of Buddhism in Mongolia that would be deemed legitimate and authoritative. However, also apparent is his aspiration to spread a form of Buddhism that is close to the Mongolian world view. There are clear Mongolian elements to his writing style and the way he presents the lives of the Buddhist masters from India and Tibet. This work thus connects Mongols and Tibetans throughout historical time on a shared Buddhist plane of existence.

By writing the Clear Mirror, Dza-ya Paṇḍita was hoping to create a work that would supplement existing works by great Tibetan monk-scholars and contribute to the learning of the future Mongolian disciples. From preliminary analyses of the writings of later Mongolian monk-scholars, the influence of Dza-ya Pandita is clear, hence there is a need to look at these closer in comparison. But for now, it suffices to say that the aspirations of this spectacular individual were fulfilled by his successors.

My research conclusions indicate that, contrary to the mainstream assertion that it was only at the end of the 17th century that we begin to find highly educated Mongolian scholar monks, there was a significant number of such individuals in Tibet much earlier in the 17th century and possibly even earlier. Those individuals who returned to Mongolian lands were in fact a minority and were mostly of noble backgrounds, leaving the figures that remained in Tibet a mystery still to be investigated. This can only be achieved through close examination and comparison of the currently known works by both ethnic Tibetans and Mongolians. Thus my hypothesis was reassured that our study of the Tibetan Buddhist world remains desperately incomplete if the Mongolian contribution is not taken more seriously.

Building on the findings of my doctoral work, the aim of my current postdoctoral project is to explore and elucidate how cultural interplay between the Mongols, Tibetans, and Manchus effected the development of a hybrid identity in a cosmopolitan Buddhist world. Only by combining the study of Tibetan, Mongolian, and Manchu, as well as Chinese literary heritages, can we obtain a clearer picture of the assimilation of Buddhism taking place during this decisive period in Central and Inner Asian history. The fruits of such research will not only reveal new insights for the study of Buddhism but also for the understanding of the Tibet-Mongolia-Qing interface, which relied on Tibetan Buddhism.

As a Mongolian and a Tibetan Buddhist who is living and traveling across the academic world of the West, studying the life and works of Dza-ya Pandita, a pivotal Buddhist scholar and cosmopolitan figure of the 17th century, has truly been an honor. He has been a constant companion throughout my research and life as my guide and as my inspiration, beckoning me deeper into the amalgamated Buddhist world in which he lived; a world that remains to be fully discovered.

Dr. Sangseraima Ujeed read for a BA in the study of religions at SOAS in London in 2012. She completed her master‘s and doctorate degrees in Tibetan Buddhism at the Faculty of Oriental Studies at the University of Oxford, graduating in 2018. She was awarded the ACLS Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Dissertation Fellowship in Buddhist Studies in 2016 and later the Postdoctoral Fellowship in 2018. She is currently based in UCSB for the postdoctoral fellowship. She is also a junior translator for the Padmakara translation group based in Dordogne, France.