With a history spanning more than 2,500 years, Buddhism has spread to almost every corner of the world. In the contemporary era, the growth of European Buddhism is well documented and acknowledged, yet the mention of African Buddhism still raises eyebrows, and details of African Buddhism remain largely unknown. This is perhaps because the mainstream media rarely seem to highlight anything other than famine, violence, and the toppling of regimes when it comes to the 54 countries that make up the African continent. However, in countries such as Congo, Nigeria, and Uganda, the seeds of Theravada Buddhism have slowly become saplings, and monks in saffron robes now walk among the uncountable peoples and clans that inhabit the most diverse of the world’s continents.

Venerable Ugandawe Buddharakkitha, born in Uganda as Steven Kabogozza in 1966, had never heard of Buddhism when he visited India in 1990. Yet learning about the teachings of Theravada Buddhism changed his life so dramatically that it could even alter the religious landscape of Uganda, as this formative experience eventually led Ven. Buddharakkitha to found a temple—the Uganda Buddhist Centre—and the Peace School to teach the Dhamma in Entebbe, the only school of its kind in the country. I met Ven. Buddharakkitha for a brief interview at the University of Peradeniya in Sri Lanka, where he is pursuing a Master of Philosophy degree in Buddhist Studies. Venerable Buddharakkitha plans to return to Uganda after completing his degree to continue spreading the teachings of Buddhism.

Sean Mós: How did you first encounter Buddhism?

Ven. Ugandawe Buddharakkitha: I was born a Christian, as most people are in Uganda. In 1990, I went to Punjab University, Chandigarh, in northern India to study for a Bachelor’s degree in commerce, and it was there that I heard about Buddhism for the first time. I met some Buddhist monks from Thailand, whose disciplined attitude towards life drew me to the philosophy of the Buddha. I started asking myself questions on the meaning of existence and the direction of my life. As a Catholic, I never found answers to such questions—instead I was taught that all faiths other than that of Jesus are considered evil. It was through Buddhism that I recognized the interrelationship between all beings and the fact that we are all responsible for our own actions. During my time in India I received five answers through Buddhism: 1) Where do we go from here? Nibbana; 2) What is the purpose of life? To achieve ultimate happiness; 3) Through which religion can I co-exist peacefully with other religions? Buddhism; 4) Who is responsible for my actions? I am; and 5) What is the way forward for my spiritual journey? The Noble Eightfold Path.

SM: Who was your first teacher of Buddhism?

UB: My first teacher was Dr. Alexander Berzin, [a teacher in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition] from the United States, who I encountered in India in 1994. I met him for the first time at the Tushita Meditation Centre in Dharamsala, where I engaged in a 12-day retreat. On the retreat I learned for the first time that all beings are interconnected. I learned that in this world it is impossible to find a being that hasn’t been your mother and father at some point in samsara. I had never thought in that particular way before, and Dr. Berzin’s lessons opened my eyes to deeper meanings of Buddhism.

I stayed in India from 1990–94, before traveling to Thailand to explore their culture and Buddhism from 1995–98. Finally, in 1999, I received an opportunity to travel to the United States, where I met my Burmese preceptor, the late Ven. Sayadaw U Silananda, at Tathagata Meditation Center in California, under whose guidance I commenced my monastic training. Eventually, in 2002, I took full ordination at the same Buddhist center.

SM: How did the Buddhist center in Uganda come about?

UB: I first thought of establishing a Buddhist center in Uganda in 1992 while I was in India, but the idea really took hold after I met His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1994. After attending a Tibetan women’s meeting in Dharamsala I also realized that there were no support groups for Tibetan Buddhism anywhere in Africa and I wanted to establish one in Uganda to raise awareness there. When I met the Dalai Lama I asked for his blessing to initiate an Afro-Tibetan Buddhist Society and a Buddhist center in Uganda. His Holiness advised me to find friends to help me achieve these goals. I looked for friends for 10 years before establishing the center and the society in 2005, so I now understand the true meaning of what His Holiness said—the Buddha himself once said that finding a spiritual friend is equal to finding one’s own spiritual life. Looking back, I can see that this whole effort was possible because I have spiritual friends in all corners of the world.

SM: How were you able to finance your plan?

UB: I started to raise funds through donors and institutes such as the World Buddhist Summit of Japan. When I addressed the summit I managed to convince many donors of the importance of such a center in Africa. Then eventually aid started to flow in, and so did volunteers from many countries such as Canada, Malaysia, and Thailand. After much strife, we managed to buy the land where we are now. Although land disputes there nearly cost me my life when someone shot at me while I was in the center (they missed), I was inspired by the good that Buddhism could do in our society, so I never gave up.

SM: Is the center affiliated with other centers in Africa or elsewhere?

UB: Well, Uganda is an executive member of the World Buddhist Summit of Japan. Other than that we have no direct affiliations or any branches elsewhere in Africa.

SM: What are the traditional religious beliefs of the Ugandan people? Do they have any resemblance to Buddhist beliefs?

UB: Buddhism is very different from any religious belief I knew about before. I was born a Catholic, yet in Africa we also have our own ancient belief system, which is known as totemism. Its importance can be understood by the fact that every Catholic or Christian belongs to a totem. A totem is a protector, a guide, and a social classification system. It’s not an organized religion, yet it has its strong points when it’s believed by the masses. For example, my totem is the otter and my family totem is the otter as well. It’s forbidden to touch, kill, or eat one’s own totem, and if I were a layman, I would not be allowed to marry someone from my own totem group. I’m still studying this aspect of our belief system, but I think African society has a belief in karma. We have a saying: “If you coincidentally kill a maggot while you eat mushrooms, after you are dead and buried the maggots will eat you.” It roughly means you have to think about your actions and there will be retribution if you do not. Of course we have no concept of hell or heaven in totemism, although we do believe in rebirth. We also believe our dead ancestors can guide us through good times and bad.

SM: How is the Dhamma being received within the Ugandan community?

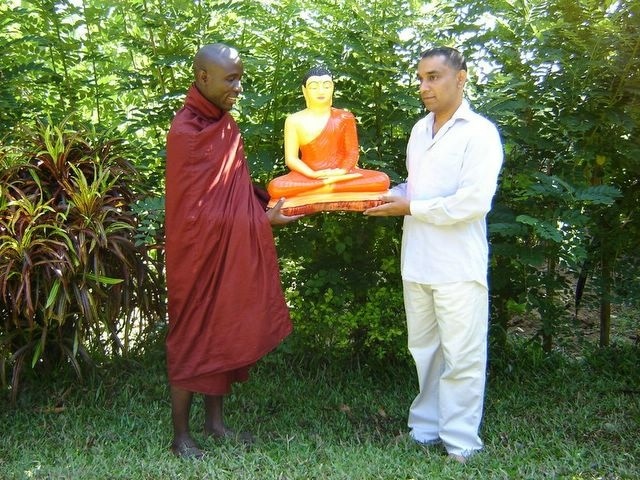

UB: I will not deny it, spreading Buddhism in Africa is not an easy task—its lifestyle and teachings are completely alien to Africans. Ours is a community that is in constant motion, and therefore we have never had a need for or a trust in sitting in silence. My mother used to say, “If you have nothing to do, sleep,” but she never said “If you have nothing to do, meditate.” We are different to Asians, so breaking through such differences is not easy. Initially when I came to Uganda clad in Buddhist robes, people used to stop me on the street and ask where I bought the robe and where can they buy one to wear. Children used to run away from me in fear. In the neighborhood where the temple was built, someone once spread a rumor that we kidnapped children and imprisoned them in the building. The reason for this rumor was the Buddha statue that I brought from Sri Lanka—someone saw it through the window and thought it was a child. That’s a good example of how alien the Buddha and his teachings are to our people. So, if we are to succeed, progress will be achieved in baby steps, and we will need homegrown Buddhists and homegrown Buddhist monks within Uganda. This is one of the reasons I started the Peace School: to teach the community about Buddhism, hoping to ignite interest.

SM: How is the center reaching out to the community?

UB: Currently in the community around the temple we have 15 Buddhist members who regularly attend chanting, Dhamma discussions, and meditation training. You might think it’s a small number, but in Africa it is not. We are hoping to reach out to more people in the future. [Before] seeing our positive contribution to African society, people were initially reluctant to join in, yet now we observe a change because they see that we only have their well-being in mind. The community we live in has a shortage of drinking water, so with the help of some donors I initiated a plan to dig a borehole so that the villagers can benefit. Funding for the project came from Malaysian Buddhists. The villagers here sometimes did not like us, but they certainly like the water we provided! After seeing the benefit of the well, I made another borehole outside of the temple as well so that those who dislike us can still benefit from the water outside the temple.

SM: What other projects have you initiated?

UB: There is the Peace School, which opens on Sundays. The children attend regular school in the morning and they can swing by for a dose of Dhamma in the afternoon at the Peace School. I wanted to expand it, to have more students and a permanent teacher, but the teacher I found later was allegedly violent towards children so I did not want him involved. Sometimes foreign volunteers visit and teach the children and other members of the community the basics of the English language. When I am there, the Dhamma school continues every Sunday, but unfortunately I am unable to stay there permanently. I have to travel for funding and also for my own education. My next aspiration is to raise money to buy sewing machines for the poor within our community. They can use these machines for additional income.

SM: You also have a resident nun, Ven. Dhammakami.

UB: Ven. Dhammakami is my mother. She is not a fully ordained nun, but she has received partial ordination from me. When I first told her about Buddhism she found the whole idea quite strange because a religion that stills the mind is rather out of place in an African context. However, when she saw my transformation, her interest grew and eventually she wanted to become a practicing Buddhist and a nun. She was never very religious, therefore it was easier for her to switch to a non-faith-based system like Buddhism. My mother is an interesting person—when I was young she used to say, “If you have nothing to do, sleep,” but now she says, “When I have nothing to do, I meditate.” She takes care of the Buddhist center during my absence.

SM: Are there plans to translate Buddhist texts into Luganda or other local languages?

UB: Yes. However, we need funding to do it successfully because translating Buddhist texts into the Ugandan context is not an easy task.

SM: What are your long-term objectives?

UB: I aspire to have homegrown Buddhism in Africa. For Buddhism to successfully take root in Africa, the locals must embrace it and make it a part of their lives. Through that, there is a possibility of them becoming Buddhist monks locally. At the moment there are only a handful of African Buddhist monks, yet my hope is to increase that number through teaching and inspiring people. It is a long and hard road, but I believe that in the long run it is a definite possibility.

See more