Since the late 1980s, Kalmykia, an autonomous republic in the Russian Federation, has undergone a reconstitution of its ethnic identity and history, of which Buddhism is an integral part. With a population of some 290,000 people, Kalmykia is situated in the lower reaches of the Volga between the Black and Caspian seas. It is officially touted as one of three traditionally Buddhist regions of Russia, along with Buryatia and Tuva. The Kalmyks, who today comprise a 60 per cent majority of the republic’s total population, have been following the Tibetan variant of Mahayana Buddhism (predominantly the Gelugpa school) since the establishment of the Kalmyk khanate in the mid-1600s by Oirat Mongols, the ancestors of the present-day Kalmyks. This continuity was interrupted by the Soviet anti-religious campaigns, which had erased Buddhism from the Kalmyk public scene by World War Two.

A widespread opinion in Kalmykia today, equally articulated by the local monastic sangha and lay devotees, is that the perceived regional distinction of Kalmyk Buddhism is embodied and revealed in the lineages of Kalmyk monks educated before the destruction of Buddhist institutions in the 1930s. A visible and proliferating tendency within the broader movement of Kalmyk ethnocultural and religious renewal is the construction of temples (Kal: khurul), stupas, and pagodas devoted to Kalmyk Buddhist history, for example, in the former locations of old khuruls or in the native regions of important Buddhist teachers of the past.

One such locus of Kalmyk Buddhist lore and history is the riverside village of Tsagan Aman, located on the bank of the Volga in the easternmost region of Kalmykia. It is a six-hour drive from the republic’s capital Elista, through the empty and unusually picturesque countryside: the pristine steppe gradually changes into desert, miles and miles of orange-red land and dry tumbleweed flying in the wind. One can occasionally see camels or herds of sheep or horses guarded by dogs, as well as infrequent stupas in the middle of the desert. This barren landscape of emptiness somewhat alludes to the religious heritage of the people who inhabit it.

It is in Tsagan Aman that the first stationary Kalmyk Buddhist monastery was built in 1798. Its construction was initiated by Orchi (Ochir) Lama, the abbot (Kal: bagshi) of Lamrimlin Khurul, which nomadized in the eastern regions of Kalmykia, the area known at that time as Bagatsokhurovskii ulus. According to Kalmyk historians, the monastery was founded before the Oirat westward migration and later brought to the Volga steppes by Torgut monks. According to tradition, the Dalai Lama named the monastery Lamrimlin (Tib: Lam rim Gling), “the place of Lamrim.” However, historians have not indicated when exactly the monastery was founded, nor whether it was the fourth or the fifth Dalai Lama who conferred the name. The Tibetan term lamrim, literally meaning “stages of the path,” denotes a type of Buddhist philosophical text presenting the stages on the way toward enlightenment, as believed to have been taught by the historical Buddha, with different versions of lamrim advocated by different Tibetan Buddhist schools. In this case, lamrim most probably referred to the works of Tsongkhapa (1357–1419), on which the Gelugpa order was founded in the 14th century. The following foundation legend corresponds to this supposition.

One year, when Lamrimlin was moving to winter pastures, following the rest of Bagatsokhurovskii ulus, a statue of Tsongkhapa fell to the ground from the back of the camel carrying it. Startled by the unpleasant incident, the monks rushed to recover it. When they came closer, they saw to their great dismay that the image of the sutra had broken away from the statue and fallen into a hollow beside it. The bagshi Orchi Lama saw this as a bad omen and said that just as the book had broken off the statue, the Buddha’s teaching would one day disappear from the Kalmyk land. For the Dharma to remain on the Volga steppes, a temple of wood and stone had to be built.

Lamrimlin Khurul continued to be an important Buddhist centre until the Stalinist purges, being the residence of the Kalmyk head lamas (Kal: shajn lama) at the turn of the century. All the same, following the destiny of other khuruls, it was abolished in the 1930s. While some parts of the complex were destroyed, other buildings and chapels were transported to neighboring settlements and accommodated for other uses. In fact, the entire village of Tsagan Aman was moved to the opposite bank of the Volga to its present-day location.

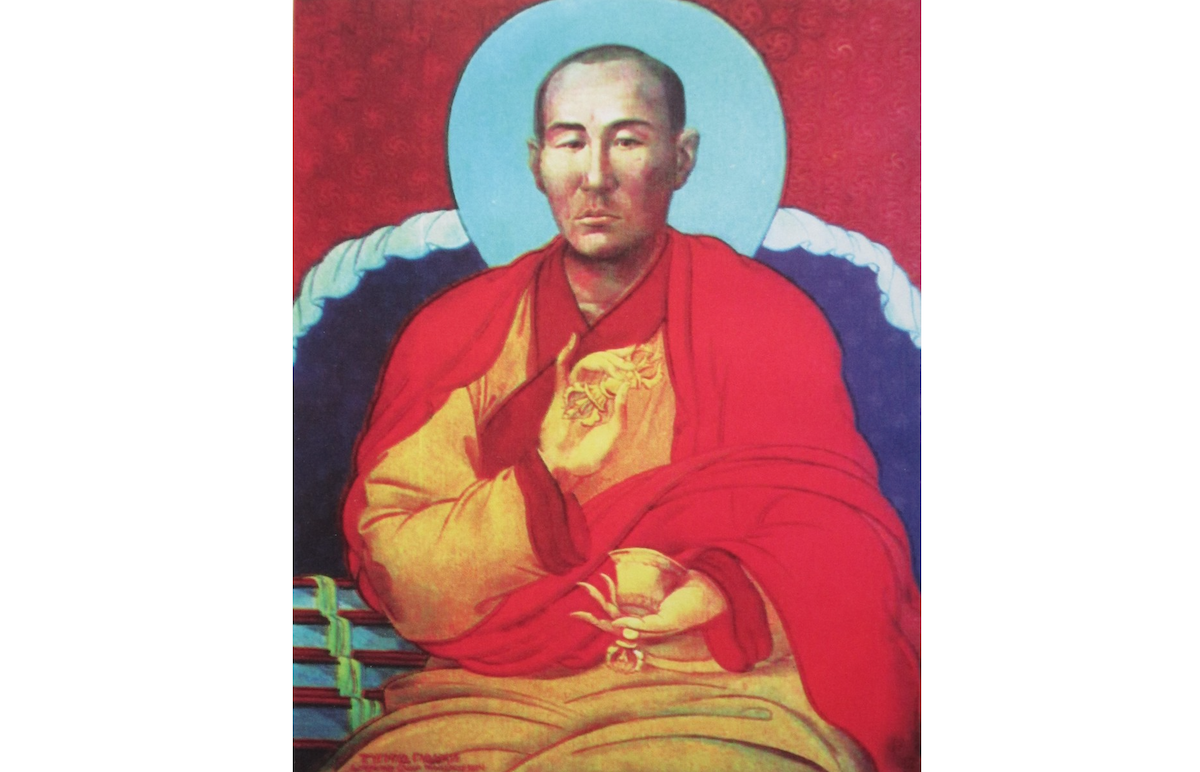

Soon after the Kalmyk deportation, the village of Tsagan Aman, this time on the other side of the Volga, resumed its role as an important—albeit underground—Buddhist centre throughout the following decades of the Soviet era. This “secret” renewal began when a dissident returnee monk, Ochir Dordjiev (1887–1980), known in Kalmykia by his Buddhist name Tügmed Gavdji, settled there in the 1960s. Another Kalmyk monk, named Ochir, was to continue the mission of making and fulfilling prophesies in order to keep flame of the Dharma burning. While a young boy, he was sent to a khurul in his native region, which is today Astrakhan. Gavdji continued his Buddhist training at Gandan Monastery in Mongolia, where he studied together with the future khambo lama of Buryatia, Jambal-Dorji Gomboev. He is also said to have studied for some years at one of monasteries in the traditional Tibetan region of Amdo, near Lake Kokonor, in the present-day Chinese province of Qinghai. After returning to Russia in the early 1920s, Gavdji was invited to teach at Datsan Gunzechoinei in St. Petersburg by Agvan Dorjiev, a Buryat lama and Tibetan ambassador to the Soviet Union.

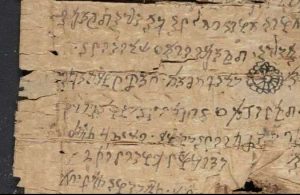

In 1935, Gavdji was arrested for being a Buddhist monk and sentenced to five years in a Gulag labor camp in Kazakhstan. A few years after his release, Gavdji was exiled again to eastern Siberia, this time in connection with the Kalmyk deportation of 1943. During this period of exile and after returning to Kalmykia, he continued to perform religious services for people. Gavdji’s house in Tsagan Aman virtually became a functioning khurul, although unregistered and illegal, where Kalmyks gathered in great numbers for Buddhist festivals. He also had a vast collection of Buddhist literature, some of which he translated into Kalmyk. Gavdji also covertly treated people by means of Tibetan Buddhist medicine. He was believed to possess extraordinary healing and visionary powers and therefore people, even members of the Communist Party, frequently resorted to him in secret and often at night. I was told that he could even state the person’s name, age, and the reason for the visit before the visitor introduced himself. Popular accounts portraying his magic abilities are frequently retold by the locals.

In the 1990s, when Buddhism was no longer illegal in Kalmykia, a new khurul was built in Tsagan Aman in honor of Gavdji next to his old wooden house. The lama of the village khurul is Gavdji’s grandnephew, Eduard Shavinov, well known in Kalmykia as Balji Nima, the name given to him at birth by his granduncle.