Tibet is not only romanticized in the West, but also among people of China. Situated on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, the highest plateau on Earth, Tibet is seen as a sacred place close to heaven. While China is going through dramatic economic and social changes, many Han Chinese are turning to Tibetan Buddhism for spiritual guidance. They are also sponsoring the activities of Buddhist masters from Tibetan regions, including building monasteries and printing books. However, a comprehensive understanding of Tibet is still lacking, even among the most pious Buddhists.

To showcase the richness and diversity of Tibetan culture, the Capital Museum in Beijing opened a special exhibition titled The Culture of Sky Road—Exhibition of Tibetan History and Culture on 27 February. Sponsored by the People’s Government of Beijing Municipality and the People’s Government of Tibet Autonomous Region, the exhibition is co-organized by the Beijing Municipal Administration of Cultural Heritage and the Tibet Autonomous Region Administration of Cultural Heritage. Some 216 cultural relics from 21 organizations in Tibet, Beijing, Chongqing, Hebei, and Qinghai have been gathered for the exhibition. Among them, 180 exhibits are from museums and monasteries in Tibetan regions. Many of the objects have been kept in prominent monastic collections for centuries, including Jokhang Monastery (大昭寺), Tashi Lhunpo Monastery (扎什伦布寺), Sakya Monastery (萨迦寺), Shalu Monastery (夏鲁寺), Mindrolling Monastery (敏珠林寺), Densatil Monastery (丹萨梯寺), Gurugyam Monastery (故如甲寺), and have never been displayed to the public before.

The exhibition is organized under four themes. Starting with the origins of civilization on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, the exhibition goes on to demonstrate the interactions between the inhabitants of plateau and neighboring regions via the Silk Road, the Tang-Tubo Road, and the Tea Horse Road. The third section illuminates the development of Tibetan Buddhism, while the final theme focuses on political and religious connections between the Tibetan states and successive Chinese dynasties from the Tang to the Qing periods.

While most people readily associate Tibet with Buddhism, the first section of the exhibition reveals evidence of early cultures on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau from long before Buddhism arrived. One of the oldest artifacts on display is a piece of Neolithic pottery excavated in Karub Village in Qamdo, in the late 1970s. The discovery of a settlement at Karub extends the cultural history of the Tibetan Plateau to 4,000–5,000 years ago. In terms of technique, Karub pottery is similar to that from other Neolithic cultures in the Yellow River regions, such as the Majiayao. The pottery is finely made—elaborately carved and painted in red and black. However, its two-bodied shape is unusual, and it is the only example found in the Karub ruins. Therefore, scholars speculate that it may have served the tribe as a ritual object.

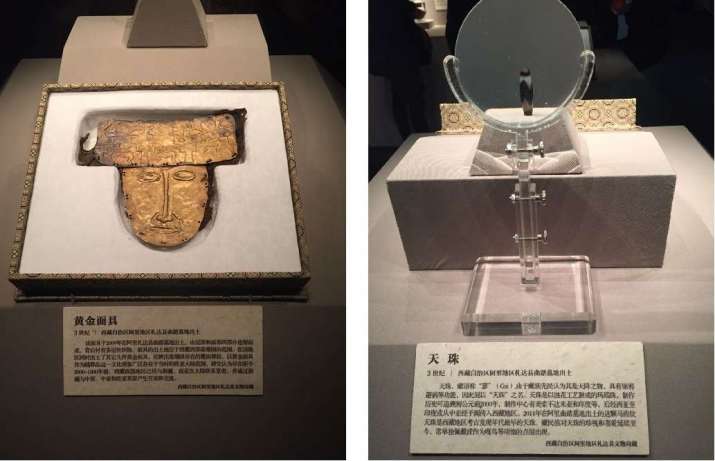

Archaeological discoveries also serve as testimony to early interactions between the peoples of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and other regions. Entering the exhibition, the first object one sees is a piece of cylindrical agate decorated with zigzag stripes in different colors. Called gzi in Tibetan, beads of this kind are believed to be jewels from heaven with auspicious and protective powers. The techniques used to craft these beads have become a mystery to us today, but archaeologists have traced their origins to Mesopotamia and India, and argue that the techniques were introduced to Tibet through Khotan. Dated to the third century, this specific bead is the earliest known gzi found through archaeological investigations.

The bead was excavated in 2014 in the Chu vthag Cemetery in Zanda County, Ngari Prefecture. The site has been identified as a tribal burial ground from the Zhang Zhung Kingdom (c. fourth century BCE—c. seventh century CE). Zhang Zhung culture is pre-Buddhist. Bon had been the dominant faith on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau until the Tibetan Empire (618–842) annexed Zhang Zhuang and introduced Buddhism. A gold mask in the exhibit, dated to the third century, was also found in the cemetery. The mask is just one millimeter thick. The horizontal panel at the top is incised with birds and goats, whole on the back of the mask, textiles are attached. Similar burial masks and their associated practices were common in Eurasia both before and during the Zhang Zhung period. These artifacts indicate the complexity of Tibetan culture, which was shaped by indigenous traditions and foreign influences.

Nevertheless, most items in the exhibition are inspired by Buddhism, and the selection is superb in terms of variety and rarity. They are arranged in three perspectives: the first illustrates the style development of Tibetan Buddhist art by juxtaposing Tibetan sculptures with those made in India, Kashmir, Nepal, and the imperial workshops of the Chinese dynasties. In the second, an array of Buddhist objects, including not only sculptures, sutras, and thangkas, but also theatrical costumes, medicine tools, and musical instruments, are organized around the 10 sciences of Tibetan culture—the Five Major Pancavidya and the Five Minor Pancavidya. A splendid thangka depicting the movements of the Sun, the Moon, and other planets and constellations of the zodiac, for instance, demonstrates the mastery of both astrology and art. In the third part, artifacts are grouped according to their affiliation to the different schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

Photo by the author

The last theme of the exhibition starts with Bunian Tu (步辇图), one of the most famous paintings in Chinese art history, which illustrates Emperor Taizong of the Tang dynasty receiving a Tibetan envoy sent by Songtsen Gampo in 634. After the meeting, Taizong agreed to marry his daughter Wencheng to Songtsen Gampo. Imperial seals and documents from the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties shed light on the political and religious dynamics between Tibet and Chinese inland, evincing praise for the pluralistic and multi-ethnic characteristics of China.

Regardless of one’s political views on current affairs, it is evident that the organizers of the exhibition made a genuine effort to educate the general public on the history and culture of Tibet. From Neolithic artefacts to contemporary videos, Tibet is made a reality instead of an idealized paradise isolated by snowy mountains. Nowadays, when so many views are shrouded by ignorance, imagination, and misinterpretation, it is beneficial to actually try and understand the subject in discussion. This exhibition is constructive in cultivating public appreciation and the preservation of Tibetan culture.

The Culture of Sky Road—Exhibition of Tibetan History and Culture will run through to 22 July, coinciding with another special show, Art, Culture, and Daily Life in Renaissance Italy. All exhibitions are free of charge, but advance booking is required.