Finding a space to grow food is a challenge in urban areas. Even though a space might be available for growing food, opening up this space not only for human beings but also for bees and butterflies is even more challenging for two reasons: one is the challenge of overcoming selfishness and sharing a very limited space with other living beings, the other challenge is attracting butterflies, bees, and other biodiversity to an urban setup. The answers for these two questions can be found in Buddhist philosophy and a person can overcome these challenges by becoming involved in Buddhist gardening.

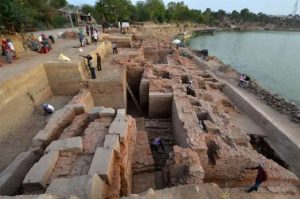

Gardening has been a common activity for human beings since the beginning of time. But gardening with Buddhist philosophy is probably a new concept for many people. The “Metta Garden” in Sri Lanka is an urban garden developed as a poison-free organic garden following Buddhist principles. The plot of land that houses the garden was once an abandoned area in a semi-urbanized neighborhood. The plot, 40 x 20 feet in size, was originally used by the neighbors as a garbage dump. I bought the land in 2015, and since then we have gradually developed it as a Buddhist garden.

We started by leaving the land alone for a period of time to allow the vegetation to grow naturally and so we could identify the indigenous species of plants and insects. Since the land was used as a dump and for burning solid waste, the soil was not very healthy. In the period that we left the land alone, no bees were observed and only six species of butterfly were recorded. In addition, no earth worms were found on the plot, not even where the soil was damp.

The design of the garden was based on the idea of causing minimal disturbance to the natural growth of the plants on the land. We divided the garden into four sections by creating 1-1/2-foot-wide walking paths that meet in the center, demarcated by a cherry tree. The four sections of the garden represent the four fundamental elements described in Buddhist philosophy: apo (water), thejo (heat), vayo (air) and patavi (solid). A small pond with water lilies was created in the apo section, and we planted vegetable and fruit plants, which are known to have a more watery constitution (e.g. sugarcane, papaya, cucumber). Thejo was represented by a composting pit—a common feature of the process of composting is the generation of heat—and plants with heat qualities, such as chilies and tomatoes. Expressing vayo was challenging, but in the end we planted tall plants. Wind makes the plants move, so it is easy to understand the vayo element. A small rock garden was established in the patavi section, and in this section we grow yams, corn, and few other vegetables known for their hardness. All the vegetable, herbal, and flower beds were designed in the form of a mandala, following the permaculture design concept.*

The main entrance to the garden leads to one of the four paths, paved with rough stones. When entering the Metta Garden barefoot, you feel the roughness of the stones. This roughness represents life. Living in the world, or in your own society, is not always a smooth path. Most of the time our minds are shaken with negative emotions such as anger, envy, or hatred, and there is pain and suffering in our day-to-day life. The rough path reminds us of all the burdens we carry when entering the garden, but then the journey through the garden starts. The next path is paved with smooth pebbles and invites us to settle your mind, enjoy the garden with all its living beings, and touch the plants. The path that follows is filled with sand which is smoother than the pebbles. As our feet and toes touch the sand, we are reminded that gardening activities invlolve all five of our senses, we further our understanding by smelling plants, touching them, and sometimes even tasting leaves. The last path is made of grass turf. Entering that path you feel a cool, soothing, comfortable sensation through your feet, signaling the mind to drift to more peaceful thoughts. The smooth feeling of the grass represents life without anger and suffering. A mind with peaceful thoughts will lead to actions that are calm and peaceful. The walking meditation described above addresses all five of our sensory faculties, invites us to understand life, and allows us to make a connection made with plants and other creatures in the garden. Learning to pay respect, show gratitude, and interact with the plants and the other inhabitants of the garden, while working, walking, or just being in the garden, is practicing Dharma.

The Metta Garden is a place for experiencing loving-kindness (Pali: metta). It is a space for many non-human living beings, seen and unseen. Microbes, earthworms, butterflies, bees, birds, and many plant species. All these living beings share the space with the humans who walk in the garden or tend the plants. It is a space to practice compassion for those suffering (karuna), where one can experience unconditional love (muditha), and understand the balance between ups and downs (upekkha). When the weather is good, and there is good soil and nutrients, plants grow healthy and more movement can be seen in the garden due to the rich biodiversity. When the weather conditions are not favorable, plants might die and there will be less biodiversity. This is the reality of life, and this balance of ups and downs is needed to continue an unshaken lifestyle.

The garden is a place where one can practice meditation. Walking mediation, metta meditation, and breathing and concentrating on bird calls are few types of meditation one can practice during gardening. Weeding is another type of meditation, as it gives you time to sit down and patiently remove unwanted weeds from the turf or the vegetable beds. It is same as the Buddha’s teachings on how to get rid of bad thoughts, which are like weeds, and maintain positive thoughts by practicing the Dharma.

Today, the Metta Garden provides us with food. It functions as a training plot for youngsters, and it is home to 64 species of butterflies, bees, and birds that make their nests in the trees. Many insects can be found in the garden, and the soil is full of earthworms. Some bigger animals such as monitor lizards, squirrels, and mongoose are also present. Many neighbors bring their kitchen waste to the garden to make compost, and people come and pluck flowers to offer to the Buddha. The garden houses rare medicinal plants and people have recognized this space as an “urban forest.” One of the teachings of the Buddha was “Arama Ropa Wana Ropa”—constructing monasteries and growing forests is a noble action, and making the Metta Garden feels like one such noble action has been accomplished.

* A system of agricultural design principles focused on simulating or using existing patterns from the natural ecosystem.

Kanchana Weerakoon is the president of Eco Friendly Volunteers (ECO-V), Colombo, Sri Lanka.

See more

Buddhistdoor Special Issue 2017