Image courtesy of Dance Division, New York Public Library

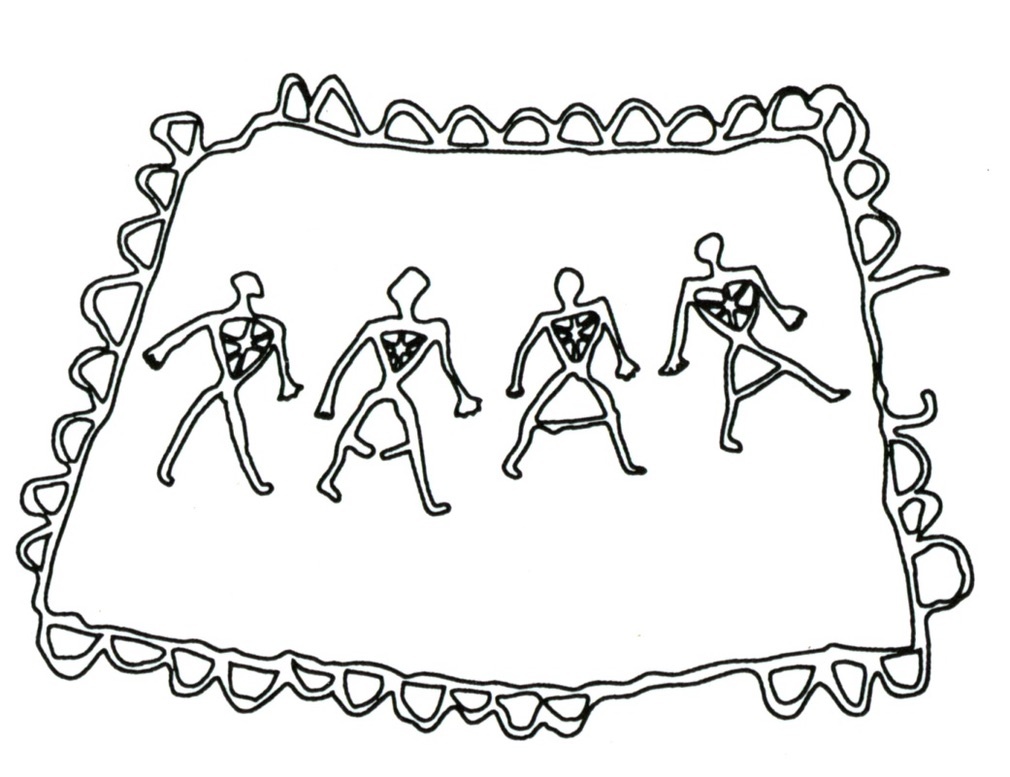

I recently had the pleasure of delivering a lecture to graduate students, all professional artists, at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I was asked to speak on the watershed 1913 Ballet Russes production of Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring), composed by Igor Stravinsky, choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky, and produced by Serge Diaghilev. Set and costumes by Nicholas Roerich. Sacre was revolutionary modern art depicting a mythical pagan Russian ritual in which a young woman must dance herself to death in order to marry the Sun and so ensure the proper order of the seasons.

Ballet re-constructor Millicent Hodson explains: “Sacre is an artistic excavation of archaic ethics: what a society is willing to sacrifice to sustain wholeness with the seasons and the cosmos.” It was a virgin sacrifice, told onstage. The audience rioted; the police were called. It was performed only nine times, including rehearsals, and never performed again as intended. “The work of a madman. Sheer cacophony,” wrote the composer Giacomo Puccini. People were outraged by the score and the choreography. Now, Sacre is upheld as a modern masterpiece and a ballet event that transformed the centuries-old dance form.

Other revised versions failed. The original production was reconstructed as faithfully as possible in the late 20th century by Millicent Hodson, with the visionary Joffrey Ballet. That production is kept alive in a number of major ballet companies around the world, with the gratitude of balletomanes for some semblance of the earthshaking ballet that remains. In the same decades, a number of modern dancers and choreographers have taken on Sacre: famously as a solo by Molissa Fenley, and as full productions in the hands of modern masters Pina Bausch and Anjelin Preljocaj. There are many other Sacre choreographies now, remarkable considering Stravinsky’s conclusion after the Paris fiasco was that his ballet could only ever be performed as music.

Where the Nijinsky/Stravinsky original 1913 production depicted a virgin sacrifice, it was highly ordered, performed by the whole society, and shown as high art. It was holy, actually sacred to Nijinsky. The set and costumes were designed by theosophist and explorer Nicholas Roerich, who famously traversed the Himalaya looking for Shangri-la, leaving us beautiful paintings of Tibetan landscapes and Mongolian monasteries, some faithfully depicting Buddhist dances, which themselves had very old roots. Sacre shows a considered and prehistoric relationship between humans and animals; although not animalistic, it is ritualistic. An awe accompanied the rite.

By contrast, the Bausch and Preljocaj versions, both artistically skillful and powerful pieces, nevertheless included in their interpretation of what was elemental and primal, behavior that is base, amoral, sensational, and overtly sexual, not a grandly united process of elemental interaction. By this, I mean specifically: groups of men violently tearing the clothes off of a woman; men dragging a woman by her hair through mud; animalistically trapping a naked woman in an earthen pit. Where did this idea come from: that ancient ritual was base and lawless, demonic and even depraved? That it violated women? This seems more a modern sensibility, a Hobbesian observation that, at heart, life is nasty, brutish, and short.

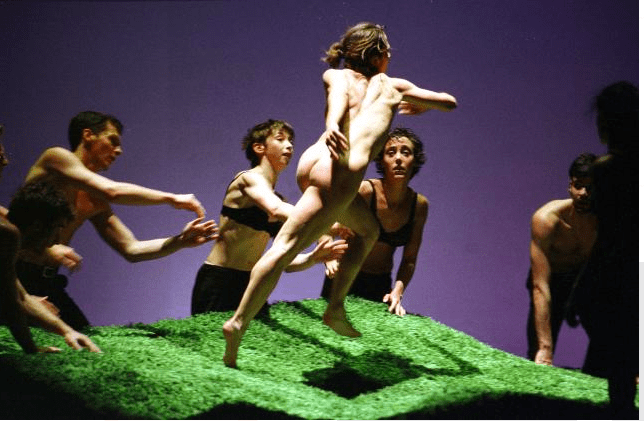

Please enjoy these images from among the oldest known depictions of ritual in the world. The shaman is from a cave in France, the petroglyph is from India. There is nothing base in these images. Instead, emergent order is shown. Destiny is patterned.

Image from Core of Culture

Image courtesy of Newberry Library

Disrespect toward women is not something found in ancient rituals. Fertility was essential. In Western civilization, as recorded in Euripides’ Bacchae, it is the women who are dismembering men in the Bacchic rites. It is interesting to note that the Greek word orgia (orgy)was coined precisely to describe Bacchic rites of fulfillment and divine madness. It did not mean a lot of people having sex together, although there was a sexual component. The early Italian explorer Giuseppe Tucci wrote that esoteric tantric meditation art depicting sexual union was orgiastic, in this truest sense of full ancient rites, implying dancing and mysticism. Nowadays, the word is rarely appreciated for its original and complex meaning. Tucci was a linguist. Fortunately, by the time my generation learned the word “tantra” it did not conjure to mind love gurus and free sex. It was a spiritual practice and a form of art. The lingering notion that tantra is fundamentally about sex is mostly fanciful.

Image courtesy of Core of Culture

One standout 20th century depiction of ancient rituals can be seen in the 1916 silent film Intolerance by D. W. Griffith, specifically the sections treating the fall of Babylon. It is a huge production, more than 1,000 dancers, sets a kilometer in length, and the depiction of more than nine distinct Babylonian rituals from the Temple of Ishtar to the steps of the fabled city itself—all this in addition to battle scenes attending the fall of Babylon. There is a decadence, an effusion of falling cultural elements, but there is also an imagined dignity and order. How did a century’s “knowledge” bring us from imagined Babylon to dragging women by their hair as a way to depict an ancient ritual?

Seminal modern dancers with vaudeville roots Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis choreographed the ritual dances for the Griffith film. The same pair went to Asia in 1925–26, where they performed and made films of Asian dances that serve as a baseline for pre-modern Asian dance even today.

Ted and Ruth brought to life the fall of Babylon from thin air, but there was something integral in their understanding, leading Ted to become the first Western dancer to document and write on Buddhist dance and ritual.*

The oldest known depictions of humans include masked shamans dancing and hunting—not fighting or killing other humans. The depictions show order and cosmic consciousness, not chaos and depravity. Dance brings order, dance is a symbol of order. Still, early accounts of Buddhist dance painted a ghoulish and dark impression. Some explorers had more openness to other religions and customs but upholding the superiority of Christianity was part of presenting Buddhist dances to the West. Many early explorers were also travel writers of their fantastic tales of unknown places, public speakers who shared images, and popular figures in the public imagination. These explorer-writers wrote some rip-roaring accounts.

Gaining a sense of what a “scientific” expedition was in the late 19th and early 20th centuries requires a mental reset. As difficult as it is today for young people to imagine life without computers, we must imagine terrain with no roads, more than a hundred pack animals, upwards of 50 men as a support team. The arrival in Central Asia of such foreign expeditionary teams as legendary Swedish adventurer Sven Hedin’s, manned as they were with scientists, cartographers, photographers, botanists, doctors, and journalists, was itself an event. Such an expeditionary caravan encountering a Mongolian Buddhist dance ceremony was a meeting of worlds as pageant and caravan came together. Mutual respect colored the interactions, doubly chronicled by Hedin and Haslund, aided by German filmmaker Paul Lieberenz, whose photos adorn this article.

Lieberenz, from Haslund’s book, Men and Gods in Mongolia, (Kegan Paul, Trench Trubner & Co,

London. 1935.) Top: Horned masked dancer, retinue of Mahakala. Middle: Black Hat zhanag dancers

huddle in the middle of a sorcerer’s dance. Bottom, the monastery oracle, a trance dancer who

delivers a divination. Images courtesy of the Gunner-Jarring Central Eurasia Collection

Sven Hedin, who appreciated the Buddhist dances he saw, drew and painted them realistically. He also encouraged every member of his teams to write books and leave accounts. Early Danish travel writer and anthropologist Henning Haslund (1896–1948), did just that after joining a Hedin expedition for three years from 1927. Haslund avoided the moral condemnation that British soldier and professor Laurence Waddell (1854–1938) heaped on Buddhist practices as superstitious nonsense. Waddell routinely explained Buddhism with comparisons to Christianity, using terms such as “Buddhist Eucharist.” Haslund, who gets many things right, doesn’t fail to represent the Buddhist dances as something savage. The dances, according to Waddell, were “wanton mummery.”

Haslund included musical notation as part of his book’s ethnography. 1928.

Image courtesy of the Gunner-Jarring Central Eurasia Collection

Haslund takes pains to state that the terrifying deities are protectors not devils. In Haslund’s words, the Mahakala group dance “rose to a wild ecstasy,” wearing costumes of “savage color” as the music became a “diabolical uproar.” Among the spectators, on the women’s side “hysterical seizures spread like an epidemic.” When the dancers stood still, it was as though they were “petrified by some magic formula.” Finally, the music “strained to a deafening din,” and Mahakala “threw himself into a maniacal dance.” Good stuff.

Upon the chance to witness monastic oracles, Haslung observed “somber voices, outbursts of snorts and groans.” The Oracle “plunged himself into a wild whirling dance, a fantastic impression of freakish rhythms, queer compositions of form, and somber harmonies of color.”

Interpretations are complex. Haslund devotes more than two chapters to the monastic dances, and in fact gives rather precise and wonderful accounts from which I have drawn these colorful phrases. From reading his book, I can tell immediately what dances he saw. Dance is not easy to describe; it disappears as soon as it happens. When it is something utterly new to an observer, of course, people use the touchstones they have to understand it. Haslund respected the religion and wrote in more than one place that he believed that the piety and sincerity of Buddhists matched anything in the West.

Central Asian dance. This shows too how integrated dance was as part of life, and the value

of artistic ethnography. 1928. Image courtesy of the Gunner-Jarring Central Eurasia Collection

Haslund admits, after being “mauled and battered by the raging breakers of a human sea,” that a mysterious howl was heard. “The howl pierced through bone and marrow and lacerated our already overwrought nerves.” Part of the splendor of early explorer accounts is the fabulous writing they used to tell their stories. Their use of language was more sophisticated than today’s writers. Description mattered. Few things are more exciting than Hedin’s harrowing accounts of surviving a storm on a Tibetan lake in a small boat. Haslund’s book, like those of other well-known explorers, is a real page-turner.

It is our opportunity today to learn the character of these men and women explorers and to understand the reality of their lives. From a diabolical uproar to naming this Buddhist dance cham, and recognizing it as a yogic expression of Vajrayana Buddhism, is a fulsome path toward danced enlightenment. We are able to compare the accounts of early explorers with actual dance because the dance has survived, although many of the monasteries visited by Central Asian explorers have not.

* Ted Shawn on Buddhism (Buddhistdoor Global)

See more

Related features from BDG

Nicholas Roerich: Master of the Himalaya

Mongolia: A Complex Dance Survival

Mario Fantin: Mountaineers, Ethnography, and Buddhism

Giuseppe Tucci, an Orgiastic Aha! Part One