I’ve been spinning my wheels for too long. I’ve been both busy and recumbent. I have many thoughts that sprint the treadmill, swim, and tango, while languishing alongside the tumbleweeds and dust bunnies of my empty brain. As I write this, the English skies outside my window are vacillating between clear blue and thunderous leaden clouds with sheets of rain lashing down in high winds. It’s pretty impressive in its own way. It feels as extreme as the vacillations of my own mind.

I feel fortunate to be warm and sheltered during this strange storm. I think of tropical monsoons, which remind me of the Kathina festival, born some 2,500 years ago to aid Theravada monks after the rains—a time of giving, not least of food and cloth. This puts me in mind of this harvest time of year in the Northern Hemisphere and of the festivals that were born from Celtic traditions some 2,000 years ago. One of eight early Celtic celebrations based around the annual cycles, Samhain* marks the beginning of winter and one could argue that is also a time of giving, not least the giving of thanks for the season’s crop harvest.

Countless global practices recognize that the seasonal darkening of the days thins the veil between the realities of the living and the departed and the otherwise. Clothes were donned, often as a disguise from the fae folk and the disembodied or vengeful momentarily undead. At the time of writing, we stand in the “mist” of these global festivals. I note the similarities and muse briefly on how history seems to birth such shared experiences that we assume are so disparate, not least due to geography and maybe about 500 years.

This brings me back to one of my long-time preoccupations: symbols and our long-standing intimate relationship with shape. Anthropologist Genevieve von Petzinger’s research appears to prove that for 30,000 years—give or take—(only) 32 symbols were used throughout the “inhabited” world. We can never know for sure what these markings meant to the artists. Perhaps it was merely because they were easy to execute. Maybe they were marking down their shamanistic experiences. Or perhaps the signs signified something that they could recognize—a visual onomatopoeia, if you like. Even now, it’s difficult to know for sure what is utterly inherent to our being and what has been imprinted. We are hard pushed to distinguish our own tastes and dislikes and reactions from what has been learned since before we could talk. However and almost regardless, images affect us. There is alchemy in art. It is like ocular yoga.

My brain is still distracted by the clouds and by my dysfunctional printer, but I can feel it exciting as I think about the “magic” of imagery again.

Alchemy was the transmutation of a base substance into something pure. Lead into gold by the chemists of old, and the mundane human experience into gnosis by those of a more mystical inclination. Today, regardless of one’s religious or spiritual perspective, transmuting and transcending negativity is a practice that most people agree is beneficial for holistic health.

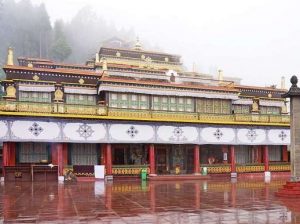

There is a word in Tibetan Buddhism: thongdrol, which translates as “liberation by sight.” At a very rudimentary level, we can describe it as the belief that planting metaphorical seeds within the viewer’s mind will ultimately offer liberation from the endless cycle of rebirth. Specific use of deity imagery was and is used for this purpose.

We process light frequencies and imagery in color and symbolic languages—letters and pictograms. It is how we communicate beyond sound and leave our informational legacy for posterity. Our brains recognize shapes as representing something particular, whether reading words or understanding traffic signs. This new information fires through our brain matter and restructures our brain biology over time, a phenomenon known as neuroplasticity. Whatever the practices may be, visually, they require us to recognize agreed-upon, instructive symbols. And, with repeated practice, they become habit.

Humanity has recognized symbols as meaningful throughout the ages and we see some of the same patterns globally, dating back to the first cave paintings. We have no obvious way of knowing if we recognize these patterns from some cosmic blueprint inherent in our collective memory or if we initially manufactured them consciously, marking them around the world until we agreed on their meaning. The fact remains that our other-than-conscious mind comprehends symbols that our conscious mind doesn’t always understand. And they are capable of revealing their meaning during spontaneous painting or conversely, manipulating the onlookers’ processing.

This is why imagery is so powerful, why art therapy works, and why advertisers and logos are invaluable to commerce and marketing. Our emotional state affects our biology, as epigenetics proves. It is for this reason that we can call art ocular yoga. Yoga is Sanskrit for “union.” This means that certain art can help to unite our inner and outer being, our physicality with our higher self: unification for well-being through seeing.

Enough of the vacillating monkey mind. The meditational tool that is imagery will serve to focus the mind in a direction of our choosing.

And, I kid you not, the sky has cleared and the Sun is shining brightly again. Even my printer is playing nicely. For those new to planting seeds through meditating with an image, I offer you the following thoughts.

Ideally, you will meditate on the painting of your choice for a while. Select carefully. I suggest that you place your image in a space where you can quietly meditate in front of it undisturbed. Spend as long as you can and as long as you feel comfortable. When not meditating with it, simply placing the painting where you will see it regularly is ideal, as this will act akin to a subliminal reminder.

Having hydrated yourself with water or herbal tea—yes, this part is important just because it is—sit comfortably and settle your system with gentle regular breaths. Gaze into the image with soft eyes and let it slowly reveal its messages to your subtle mind. Allow yourself to merge and melt into the painting. You may consciously trace the images with your eyes or allow the picture to take you into realms of fantasy, or you may simply “zone out” while staring. It’s all perfect.

It is preferable to do this at least once a day over a month to give the brain time to reprogram itself. At times, you may feel emotional responses as feelings (emotional or physical) or memories arise. Let them. Witness them, but try not to attach to any of them. Bring to mind the reasons you have this healing tool in front of you and put your attention to that space. You may have chosen an image in response to a specific issue you would like to address, or, if there is more than one issue, focus on one at a time. However, you may also simply allow the general feeling of the artwork to wash over you.

And remember to stay hydrated. Without it, we’re sun-dried jerky.

* Pronounced saa-win.

See more

Tilly Campbell-Allen (Dakini as Art)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Dance as Knowledge, Part Three: Building a Research Team

I Spy with My Magic Eye . . .

Art, Culture, and Healing the World: A Conversation with Haema Sivanesan

The Psychology of Color: A Simple Practice in Reflection, Part Six