The earthquakes in Nepal were not merely geological—some of humanity’s oldest symbols got jumbled and tumbled. Mount Everest and the Kathmandu Valley have been wonders of the world since time immemorial. Genesis stories, the original appearances of the gods, the higher than the high came together to feed the imaginations and minds of the world’s successive civilizations.

And then the civilization of our time came to be. The worst of the West’s entitled classes transgress the sacred mountain like some faddish debutante ball. Over the years, the people once termed “sherpas and climbers” have become “the global climbing community and the workforce.” China is constructing a railway between Beijing and Kathmandu, not such a stretch from their line to Lhasa. By constructing, I mean drilling a tunnel through Mount Everest.

It is always a temptation to ascribe magnificent cosmic personalities to the grand mechanisms of Nature, but The Spirit of the Mountain had every reason to buckle and sway. The aspect of the Mountain now is ominous. Such destruction has come to the ancient physical symbols—the monuments, shrines, temples, squares, and courtyards. Such interruption in the psychic strength of the country, now rocked with fear even in its determination.

The world would do well to pause and consider its relationship to these damaged physical symbols, as well as the natural next emphasis on the intangible symbols of culture and spirit that remain. How has the world treated the spiritual treasures of Nepal? Among the world’s visitors to Nepal, more is known about the latest high-altitude stretch fabrics than the basic tenets of belief among those whose lives uphold the monuments even in ruins.

“Where is Prajwal Vajracharya?” was my first question. Prajwal is the great Newar tantric Buddhist dancer, credited for keeping the ancient dance not only alive but vital worldwide. He is 35th in a lineage of dancing tantric priests. Happily, I soon learned he was in Japan, and safe. This was a start. Nepal is much more than the Newar Buddhists and Hindu kings of Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur.

The ancient kingdom of Mustang still today has the finest dancers of the Sakya lineage of Vajrayana Buddhism even as their homes are too unstable to remain their homes, and the reality of impermanence looks like a lot of tents. Artists and elders from scores of Nepal’s minorities hold the accomplishments of their ancestors within them. Singers and painters are still singers and painters. Those who know the spiritual arts of meditation and ritual are among us yet, making symbols of their own bodies and personal practice their daily conduct.

It is not as if we are now reduced to the intangible elements of our persons, for that we always were. Tables and temples and chairs and monuments don’t last. Essence remains, the obdurate ephemeral. The lightness of our being, or not, is the wherewithal by which we interact with all worlds, mountains real and mountains metaphoric. Finally, the transmission of ancient dance traditions is the life of a choreographic idea, not the handing down of costumes.

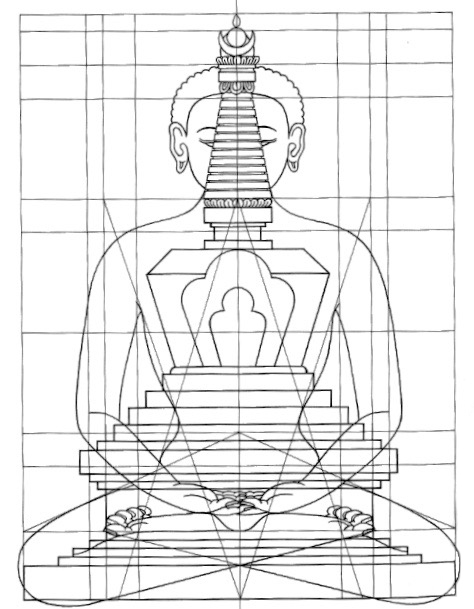

How does the body become a symbol? How does life become a spiritual practice? “They call it practice for a reason,” Prajwal reminded me. The world-famous, instantly recognizable image of a seated Buddha, symbolizing a total flow with all creation, is the perfect picture of practice. It is its own evidence. What the Buddha does is how he looks. To witness Prajwal dance is to learn this comes like breathing to those who know how to breathe. He is all divine attributes come to life.

Like most of us, I would settle for even a few divine attributes. The symbol of perfect practice that is the seated Buddha has a theoretical and geometrical relationship with the stupa, perhaps the oldest Buddhist symbol, which derives from Hindu burial domes. While it is variously developed in different cultures, each found a way to connect the symbol of perfect practice to this ancient archetype, in Cambodia more slender, in the Himalayas a reflection of the shape of snowy mountains, and in Japan, the pagoda. These refinements took centuries.

As one develops the refinements of personal practice, it enriches the practitioner to link ancient teachings to themselves as symbols of a culture they create. In terms of globalism and interacting with people, the Nepalese have provided a connection with those who carry ancient rhythm and meaning through the storms of mankind’s epochs. This living symbolism must not be severed thoughtlessly.

Symbols are commonly understood to be visual images indicating a deeper, more universal truth. This we know radically when physical symbols, such as the buildings and mountains of Nepal, are destroyed. Focus shifts to awareness of the functional energies used to connect people with one another.

The Indologist and Indian art historian Heinrich Zimmer supported the idea that every epoch must produce its own symbols as a responsibility of civilization itself. His notion of “symbol” was not limited to visual representations but included the manners and customs of daily life. Symbols function to provide access to a transcendent reality beyond the constructs of the rational mind, something ineffable but keenly sensed, a reflection of the zeitgeist multitudinous individuals manifest.

The future is not something that comes; it is something created through the symbols produced and the quality of the universal mind manifested through them as a keener awareness of human possibility. Anything less pales before the illumination of understanding. Dance on, Prajwal.

The earthquakes awaken us. What are we bringing forth? Are we observers or practitioners? If we can make our bodies symbolic, like Prajwal Vajracharya and the seated Buddha do, or our lives symbolic by being gateways to spiritual exploration, what universal truths are indicated by our behavior?

This is the first article in Joseph Houseal’s new monthly column “Ancient Dances” for Buddhistdoor. Joseph is the director of Core of Culture, an organization dedicated to safeguarding intangible world culture and assuring the continuity of ancient dance traditions where they originate. For more information, see Core of Culture.