Glimpses of living history often surprise us with their suddenness, their whimsical appearance in the hands of an unsuspecting discoverer. And it often requires many decades (or even centuries) before the world is capable, or willing, to come to terms with the implications of what was so randomly unearthed from the earth’s crypt.

This is especially true of Buddhist archaeology. So little is certain about ancient Indian Buddhism, and we are only left with some of the most tantalizing peeks: The Buddha was a real, historical person, and after he died, his cremated ashes were divided among eight kings for safekeeping and worship. One of the recipients of those remains was his own Shakya clan, after which the Buddha was called Shakyamuni.

Today, we can confidently say that those remains exist, and rest safe and sound in a small, stupa-shaped urn kept under tight lock and security in the Indian Museum in Kolkata. That urn’s inscription, engraved in the Brahmi script of Emperor Ashoka himself, proclaims: This reliquary, which is the reliquary of the Buddha, the Lord of the Shakya clan. These are the relics of the Buddha, the Lord.

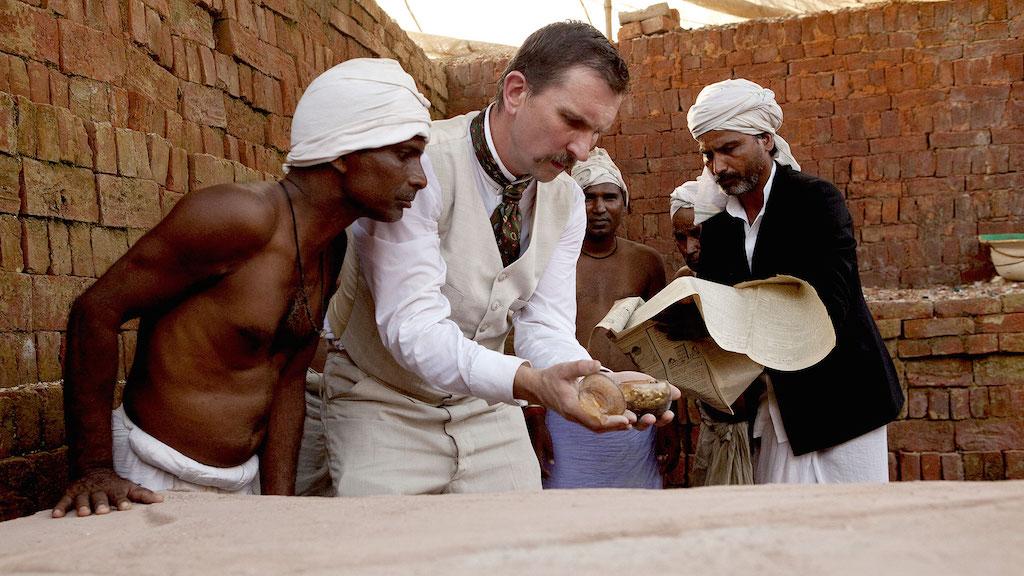

In the documentary Bones of the Buddha, the historian Charles Allen set out to clear the name of William Claxton Peppé, a Briton who discovered a collection of relics in 1898 below the stupa of Piprahwa in northern India. Not only was this documentary successful in maintaining the authenticity of Peppe’s discoveries, it also settled a much greater question: where did the Shakya clan’s portion of the Buddha’s ashes rest?

I already had my misgivings when I sat down to watch the film – historical journalism is not always of the same standard as the rigorous history of the best universities. But my doubts were more or less put to rest when Allen brought in Professor Harry Falk, a heavyweight of Indic languages with scholarly achievements too many to count here. Usually academics are hesitant to err on the side of certainty, but Professor Falk could not have been more confident in dating the urn to the Ashokan period due to the geographical and historical uniqueness of its Brahmi inscription. Piprahwa’s status as the Shakyans’ original crematorium for their Sage was also corroborated by two discoveries. The first is the size of an unearthed sarcophagus, which as Falk pointed out, correspond directly with the size of Ashokan dimensions and aesthetics and are made of the same stone. The second and most humbling discovery of all, is a smaller, humbler burial beneath Peppé’s excavation, made during the 1970’s.

Two small chambers, each with a silkstone carpet and broken redware dishes – this burial was from the time of the Buddha himself: the original resting place of the Lord’s ashes over 2500 years ago. More than a century later, the Dharmaraja, newly converted Ashoka went to the holy sites and disturbed the ashes of the Buddha by moving them into grander, jewel-decked mausoleums – in the case of Piprahwa, to the larger crypt above, which was discovered by Peppé at the turn of the 20th century. After this remarkable journey, we know that the small urn holds one eighth of the Buddha’s remains, carrying momentous implications for how we understand the archaeological site of Piprahwa and the Blessed One’s enduring presence in our world.

As the documentary concluded, I felt a great sense of comfort and closure, and a rejuvenated faith in the purpose-driven historian and archaeologist. It is on occasions like these that we see the enlightenment and benefits they bring to entire communities, like those of the Fourfold Buddhist sangha. I felt a renewed gratitude to Ashoka, whose piety was far from politically-motivated or fake: it was real, as real as the tears he shed after the battle of Kalinga, which awakened his conscience and converted him to the Dharma. And most poignantly of all, I realized that the legend of the division of the Buddha’s ashes was not mythology, historiography, or fiction. The sharing of the sage’s literal body was real, as true as the Buddha’s historical existence.

What might it have been like, more than two and a half millennia ago, to see the members of the Buddha’s family tenderly lowering his remains into the ground and covering them with flowers? What might they have said to each other? Would they have been crying softly or murmuring prayers? Would they have felt the same gratitude to their Lord as we all do, their love and reverence amplified a hundredfold by the touch of those holy ashes?