Why Meditate?

Whenever I teach Japanese Buddhism, whether in the Americas, Europe, or East Asia, I frequently run into the same assumption among students that Buddhists, for

Whenever I teach Japanese Buddhism, whether in the Americas, Europe, or East Asia, I frequently run into the same assumption among students that Buddhists, for

In my previous article,* I introduced a method of reading Japanese Buddhist texts, especially writings by the Japanese Zen master Dōgen (1200–53).** Here, I would

In this article, I would like to reflect on how to read Japanese Buddhist texts. To explain my strategies for approaching texts distant in time,

A 2008 article in The New York Times asked the provocative question whether Buddhism in Japan “may be dying out” (Onishi 2008). Unlike other, frequent claims that

I discussed pilgrimages in Japan in an earlier article on this website.* This month, I am teaching a course in Japan that involves visits to

Many package tours to Japan include a tea ceremony. Sometimes these short versions of a traditional tea ceremony––otemae or cha no yu ––take place in the tea room

Travelers to Japan notice the impressive gates that mark Shinto shrines, in Japanese, torii, as well as the shimenawa, referring to a type of rope made from

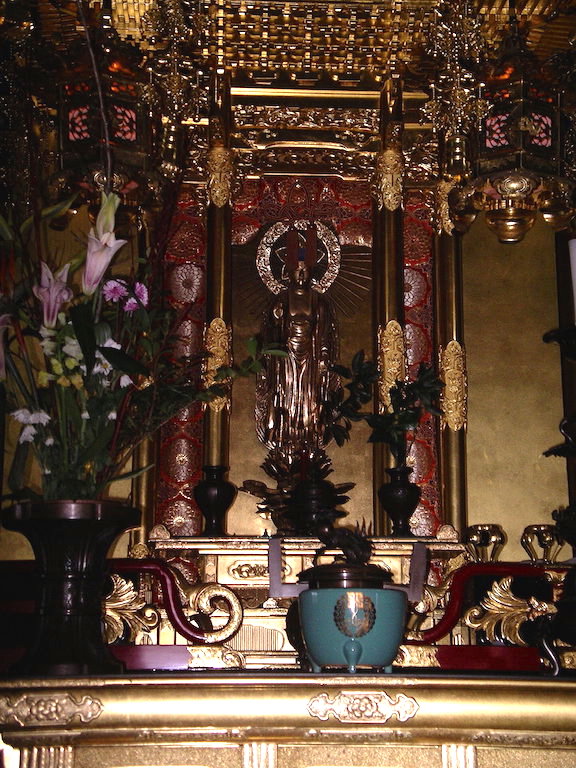

The so-called sectarianism of Buddhism in Japan has enabled Pure Land Buddhism to develop as a quasi-independent tradition within Buddhism. One of the central figures

Since the Meiji restoration in the 19th century, Buddhism in Japan has seen the development of a third category of practitioner in addition to the

Dogen’s (1200–53) Soto Zen is known for its emphasis on shikantaza—“sitting only.” In his popular Once Born Zen – Twice Born Zen: The Soto and Rinzai Schools

This is the first of a series of articles on Japanese Buddhism written by Gereon Kopf for Buddhistdoor. When I was teaching at the University