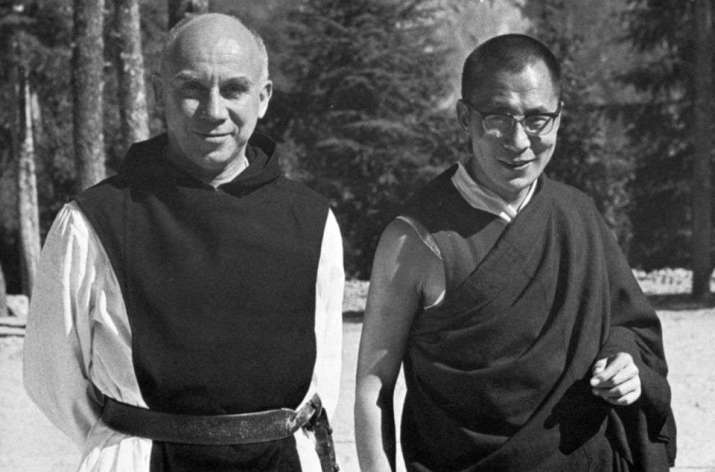

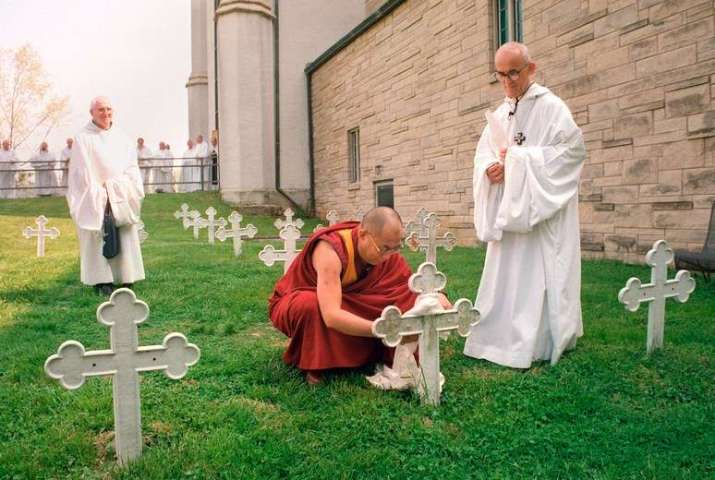

In December 1968, the Catholic monk Thomas Merton (also known by his monastic name Father Louis) died in his hotel room near Bangkok. In the years since, he has been remembered as a mystic, a poet, an activist, a renunciate, and a religious explorer. His most striking encounter with Buddhism came late in his life, but it was an encounter of such depth and sincerity that many Buddhists to this day count him among their ranks.

In marking the 50th anniversary of his untimely death, writers around the world from numerous religious traditions took pause to reflect on the many facets of Merton’s life. As a member of the Trappist order of Catholicism, much of his religious life was ruled by order, silence, and reflection on Christian doctrine. As a man living in the United States in the 20th century, however, Merton was unable to escape the social and political tumult of the world around him. In his reflection on Merton’s life, Alan Jacobs writes:

Merton was a remarkable man by any measure, but perhaps the most remarkable of his traits was his hypersensitivity to social movements from which, by virtue of his monastic calling, he was supposed to be removed. Intrinsic to Merton’s nature was a propensity for being in the midst of things. If he had continued to live in the world, he might have died not by electrocution but by overstimulation. (The New Yorker)

Indeed, not only was Merton acutely attuned to these things, he used his freedom and the power of the pen to help raise social issues to the consciousness of his readers. Daniel P. Horan recounts Merton’s sensitivity to the problems of this world:

In books with titles like Seeds of Destruction and Faith and Violence, Merton’s prophetic reflections on structural racism in the United States and the relationship between fear and violence speak as challenging a message today as they did five decades ago. . . . His wrestling with religious censors who sought to mitigate or silence his publishing about violence, racism, and the Christian responsibility to put faith into action speaks to experiences of those whose consciences call for more than banal Christian platitudes, and take the risk to work for justice in the church and world. (National Catholic Reporter)

And yet Merton also was very much a man of faith with a strong calling toward God. It has been said that Merton found no interest in the doctrines of Buddhism, but was instead fascinated by the experience of Buddhist practice, that which lay beyond words and beyond historical place and time. The American Zen teacher and retired Unitarian Universalist Minister James Ishmael Ford, Roshi, reflects on his blog:

This would prove very important to me. Continuing the article, “In 1959, Merton began a dialogue with D. T. Suzuki which was published in Merton’s Zen and the Birds of Appetite as “Wisdom in Emptiness”. This dialogue began with the completion of Merton’s The Wisdom of the Desert. Merton sent a copy to Suzuki with the hope that he would comment on Merton’s view that the Desert Fathers and the early Zen masters had similar experiences.

“Nearly ten years later, when Zen and the Birds of Appetite was published, Merton wrote in his postface that “any attempt to handle Zen in theological language is bound to miss the point”, calling his final statements “an example of how not to approach Zen.” Merton struggled to reconcile the Western and Christian impulse to catalog and put into words every experience with the ideas of Christian apophatic theology and the unspeakable nature of the Zen experience.” (Patheos)

American writer and management consultant Margaret Wheatley helps to bring us into that apophatic journey. She writes for Lion’s Roar, after discussing the idea that “hope and fear are inescapable partners” in our lives and thus the need to give up hope if we are to overcome fear:

Thomas Merton, the late Catholic mystic, clarified further the journey into hopelessness. In a letter to a friend, he advised: “Do not depend on the hope of results. You may have to face the fact that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no result at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect. As you get used to this idea, you start more and more to concentrate not on the results, but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself. You gradually struggle less and less for an idea and more and more for specific people. In the end, it is the reality of personal relationship that saves everything.” (Lion’s Roar)

As Heidi Schlumpf writes, interest in Merton is growing, “not only in the United States, but around the world, with more dissertations on his work coming from Eastern Europe and Asia, and an increasing number of courses being taught about him.” (National Catholic Reporter)

Commemorating the death of Merton, Bellarmine University in Louisville, Kentucky, where he taught briefly, is holding an artistic tribute to his life and work, running through 12 January. Also upcoming in January in Germany is a European symposium titled “To Be Human in this Most Inhuman of Ages” to mark the 50th anniversary of the death of Thomas Merton.

See More:

Thomas Merton, the Monk Who Became a Prophet (The New Yorker)

Why should anyone care about Thomas Merton today? (The National Catholic Reporter)

50 years after Merton’s death, maybe ‘we’re finally getting him’ (The National Catholic Reporter)

Walking the Path of Not Knowing: Reflecting on Thomas Merton, a Saint for Our Times (Patheos)

Finding Hope in Hopelessness (Lion’s Roar)

Merton Center events mark 50th anniversary of Thomas Merton’s death (Bellarmine University)

Quinquagenary Events (The Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)