“Uncle Joe, what was it like before computers?”

Conveying the sensibilities of an earlier time is not easy. My father was a veteran of World War Two, although he rarely spoke of it. I asked him why that was. He answered: “If you weren’t there, you don’t get it.” I was fortunate to have as a mentor during my seven-year stay in Kyoto, the great connoisseur and collector, David Kidd. David had lived in China, married into an aristocratic family, before China fell. He wrote about his experiences in the autobiographical Peking Story: The Last Days of Old Peking. But, David, too, rarely spoke about his days in Old China. I asked him why this was. He answered: “Either people don’t believe me, or they simply cannot imagine it.”

David proceeded to locate and show me a letter he’d received from The Atlantic magazine, rejecting an article he had written about his experiences designing a conference with the son of the Shah of Iran and Buckminster Fuller. It began, “Dear Mr. Kidd, Thank you for your wonderful false memoirs . . .” and went on to explain that The Atlantic did not publish false memoirs but would welcome another type of piece from him. David looked at me with an expression of amusement and resignation.“These days, it seems, editors can’t even imagine the existence of such people,” waving his cigarette in the air, “Can’t even fathom that such behavior happened at all.”

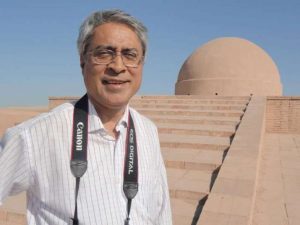

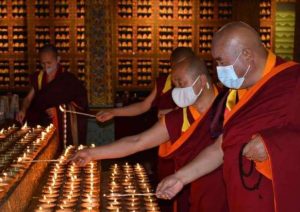

I understand this sentiment. I bought my first computer when I was 37. I had completed years of performing around the world, and then a decade of dance research in Asia and the Himalayas, without a computer or a smartphone. I continued my work, but the nature of the interactions was utterly different after the advent of computers and smartphones. The sheer numbers of people descending on remote locations as a result of mass tourism and its destructive commercial behavior did not characterize or contextualize our work. Now, it is part of the landscape. Monks and nuns now use their own drones and phones during ceremonies.

I had the great good fortune to design and conduct dance research during the final five years of absolute monarchy in Bhutan. I lived in a real medieval kingdom, traveling and working, carrying a letter from His Majesty’s Royal Government that opened all doors. I was able to experience Buddhist dances in the full social, religious, and political contexts of a tantric Buddhist kingdom led by a beloved and wise king. Who can relate to that? How? What’s the pivot of understanding?

Part of my job is conveying sensibilities—especially around the use and performance of dance—from another time, another culture, another dimension, in the case of embodied spiritual traditions. My New Year wish for my readers is that you seize those opportunities to experience the sensibilities of another time, an ancient time. Transcend to expand, embrace, and appreciate an aspect of self, new to you, though perhaps as old as time.

Three well known artists demonstrate what it means to see and embody the sensibility of an earlier or even timeless time: the seminal modern dancer Isadora Duncan, whose legacy burns brightly in its foremost interpreter today, Lori Belilove; the celebrated Newar tantric Buddhist priest and dancer Prajwal Vajracharya; and the storied British translator of Japanese and Chinese literature Arthur Waley, whose words capture the raw physicality of Chinese girls dancing more than 2,000 years ago.

When I first saw Prajwal Vajracharya dance, I exclaimed to myself, “This is what Isadora was looking for.” Isadora Duncan (1877–1927) was an American dancer, who rejected academic dancing and flouncy ballet for a more elemental, spiritual, and meaningful dance. “Dance is the language of the soul” is one of her memorable statements. She was on her own, because there really wasn’t any sacred dancing to which she could turn. So she turned to first principles, and she turned to Ancient Greece, envisioning a noble dance of freedom. Part of keeping her artistic legacy alive is continuing the shocking, brutal, emotional way Isadora danced and choreographed. It was raw. She challenged everyone. She refused to wear a corset and danced in a tunic. She was a scandal. She was the most famous woman in the world, and she revolutionized Western dance forever.

Please enjoy the great Lori Belilove performing Isadora Duncan’s The Revolutionary, from 1924, 100 years later, on 13 February 2024, for New York Fashion Week. Isadora rejected restrictive women’s clothing. She opted for free and expressive garments, such as togas. She wanted serious topics, philosophy, and classical music, not vaudeville or snowflakes. In this amazing performance, we see Isadora reaching back in time to create an authentic expression, and we see at the same time Lori bringing to life the essence of Isadora a century later, even as Lori now has lived longer than Isadora ever did. Seeing Lori dance is to know why Isadora shook the world. It’s still scandalous, jarring, beautiful, emphatic. Isadora embraced revolution and the renewal it promised.

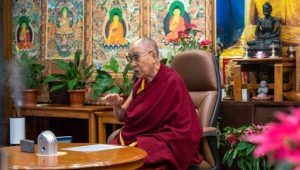

Core of Culture produced a video documentation, directed and produced by Simone Giuliani and Christiana Polites of Yangchenma Arts & Music, presenting Prajwal Vajracharya performing the ancient danced sadhana of Mahakala as part of the remarkable interdisciplinary project “Mudra and the Diamond Spheres.” Prajwal is the 35th generation Vajracharya lineage holder. Seeing him dance now is witnessing the very life blood of an ancient sensibility, a transformed consciousness, an archaic aesthetic, a pure transmission, and a time-tested mysticism.

Prajwal grew up in Kathmandu, in a renowned family of scholars and priests of the Vajracharya caste, steeped in the traditions of the Newar culture. His Vajracharya Vishekha initiation was bestowed by his father, a widely recognized lineage holder in the Newar Vajrayana Buddhist tradition, who ordained Prajwal to perform the rituals and ceremonies of this ancient religion. Since that time, he has received additional training and initiations in Nepal to enable him to further his teaching and initiate others. Thus empowered, Prajwal presided over the 2009 consecration of Nritya Mandala Mahavihara, the first Newar Vajrayana Buddhist temple in the West. Prajwal is often called on to perform sacred dances and other religious rituals throughout the world. The ancient, the timeless, and the now, meet in Prajwal when he dances.

Let me conclude this New Year wish to you: that you may discover jewels of human experience from times and places other than our own. It is to know the wider range of human capacities; to see new horizons of the human spirit. These only show that a deep humanity pervades, and demands the protection of what matters most, what cannot be replaced.

Please enjoy Arthur Waley’s remarkable translation of The Dancers of Huai-nan, a poem by Zhang Heng (78–139 CE) that is, in fact, an eyewitness account of the evanescent beauty of dance from very long ago. Happy New Year!

“The Dancers of Huai-nan” by Zhang Heng 78–139 CE

I saw them dancing at Huai-nan and made this poem of praise.

The instruments of music are made ready,

Strong wine is in our cups;

Flute-songs flutter and the song of magic drums.

Sound scatters like foam, surges free as a flood…

And now when the drinkers were all drunken,

And the sun had fallen to the west,

Up rose the fair ones to the dance.

Well painted and appareled,

In veils of soft gossamer

All wound and meshed;

And ribbons they unraveled,

And scarves to bind about their heads.

The wielder of the little stick

Whispers them to their places, and the steady drums

Draw them through the mazes of the dance.

They have raised their long sleeves, they have covered their eyes;

Slowly their shrill voices

Swell the steady song.

And the song said:

As a frightened bird whose love

Has wandered away from the nest,

I flutter my desolate wings,

For the wind blows me back to my home,

And I long for my father’s house.

Subtly from slender hips they swing,

Swaying, slanting delicately up and down.

And like the crimson mallow’s flower

Glows their beauty, shedding flames afar.

They lift their languid glances,

Peep distrustfully, till of a sudden

Ablaze with liquid light

Their soft eyes kindle. So dance to dance

Endlessly they weave, break off and dance again.

Now flutter their cuffs like a great bird in flight.

Now toss their long white sleeves like whirling snow.

So the hours go by, till now at last

The powder has blown from their cheeks, the black from their brows,

Flustered now are their faces, pins of pearl

Torn away, tangled the black tresses,

With combs they catch and gather in

Their straying locks, put on the gossamer gown

That trailing winds about them and in unison

Of body, song and dress, obedient

Each shadows each as they glide softly to and fro.Translated by Arthur Waley in 1923

See more

Related features from BDG

Be Inspired

Spiritual Encounters: In Memory of Cui Xiuwen

Ted Shawn on Buddhism