Nara, 1978. The detached jaw and moving eyes are characteristics

of antiquity. Image courtesy of Kasuga Shrine and Japanese

Ministry of Cultural Affairs

Buddhism, in its travels across oceans and along the Silk Road into China, Southeast Asia, and the world, has acted to preserve and enshrine more pre-Buddhist and non-Buddhist artistic elements than any other single movement. Courts die. Buddhism continues. Dynasties fall. Dance continues. Dances accompanied Buddhism’s spiritual odyssey across Asia, resulting in a dignified and robust pan-Asian culture of dance and ritual.

This absorptive characteristic of Buddhism is significant, adorned by many ancient signifiers. Buddhism itself is a museum, a repository of the archaic. The creation and survival of an ancient dance called bugaku is a case in point. Bugaku is a 1,400-year-old dance comprising many very ancient dances, its evolution facilitated by Buddhism at important junctures.

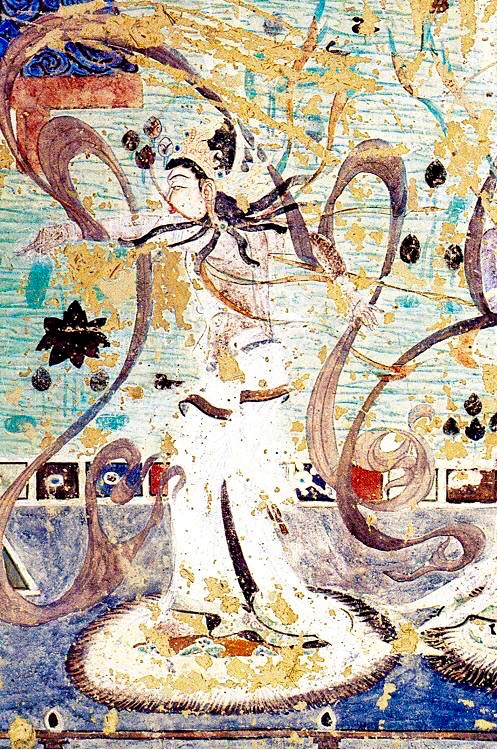

Asian dance from Sogdiana, the Hu Xuan, a female variant on a

popular whirling dance that spread widely and absorbed

transcultural elements. Image courtesy of Dunhuang Academy

Buddhism’s characteristic of assimilating—not annihilating—the cultures of the lands into which it is imported, coupled with China’s great legacy of collecting and combining dances, and Japan’s unique capacity to bring things to their most understated, abstract, and essential form, has given world culture the sublime art of bugaku. It remains today preserved in the Japanese Imperial Court, in Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples in Japan, and in the work of Taiwanese dance reconstruction choreographer and scholar Liu Feng Shueh (b. 1925).

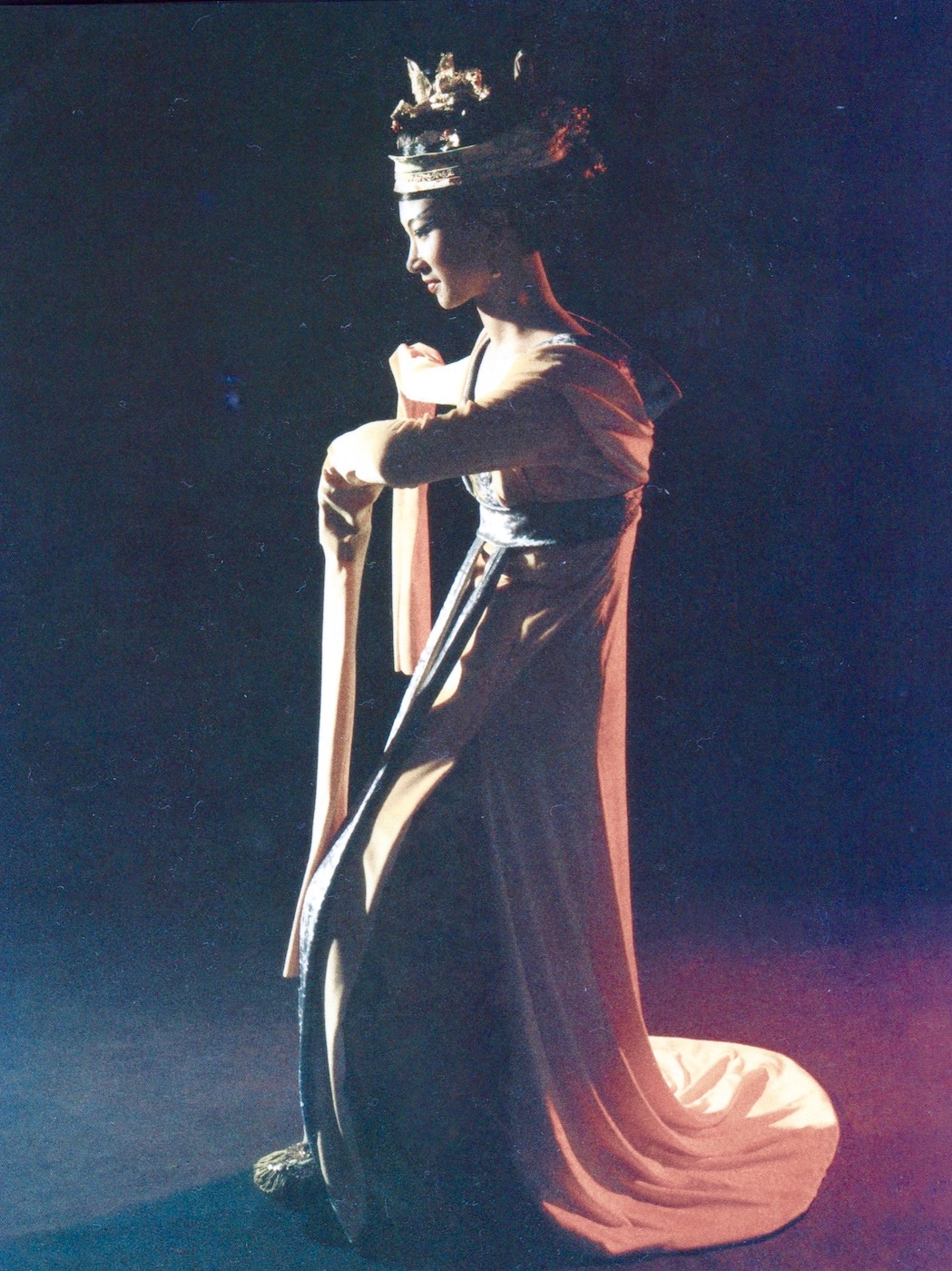

reconstruction by Liu Feng-Shueh, 2002. Image courtesy of the

Neo-Classic Dance Company, Taipe

By definition, bugaku is the dance music and dancing of the art form gagaku, which also includes instrumental and vocal music. Gagaku means “elegant music.” Gagaku dancing is bugaku. “bu” means dance, as in the word kabuki. The word music, in its ancient use, especially in China, included dance, singing, and instrumental music. A “compendium of music” included dance, poetry, and singing. A term used to name specific music was also the name of the dance, the rhythm, and the poetry. A master of music was also a master of dance. Often dancers played instruments. Musicians knew how to dance and sing. Procession became ceremony.

Just as the martial arts of Asia expanded and refined when Indian forms of fighting and acrobatics traveled the Silk Road, taking on cultural influences before reaching China, where ancient movement characteristics became the substratum of assimilation, so was dancing, even more so. Driven by delight and beauty, ceremony and sacredness, dance took on forms in cultural integration and satisfied societal needs for order and harmony, ancestor worship, and the stabilization of civilization.

Dances were status symbols. The powerful had dancers; the powerless danced. In time, the upper classes mastered evolved dances. Dancers became artists. Dance was an ever-shifting value and a constant.

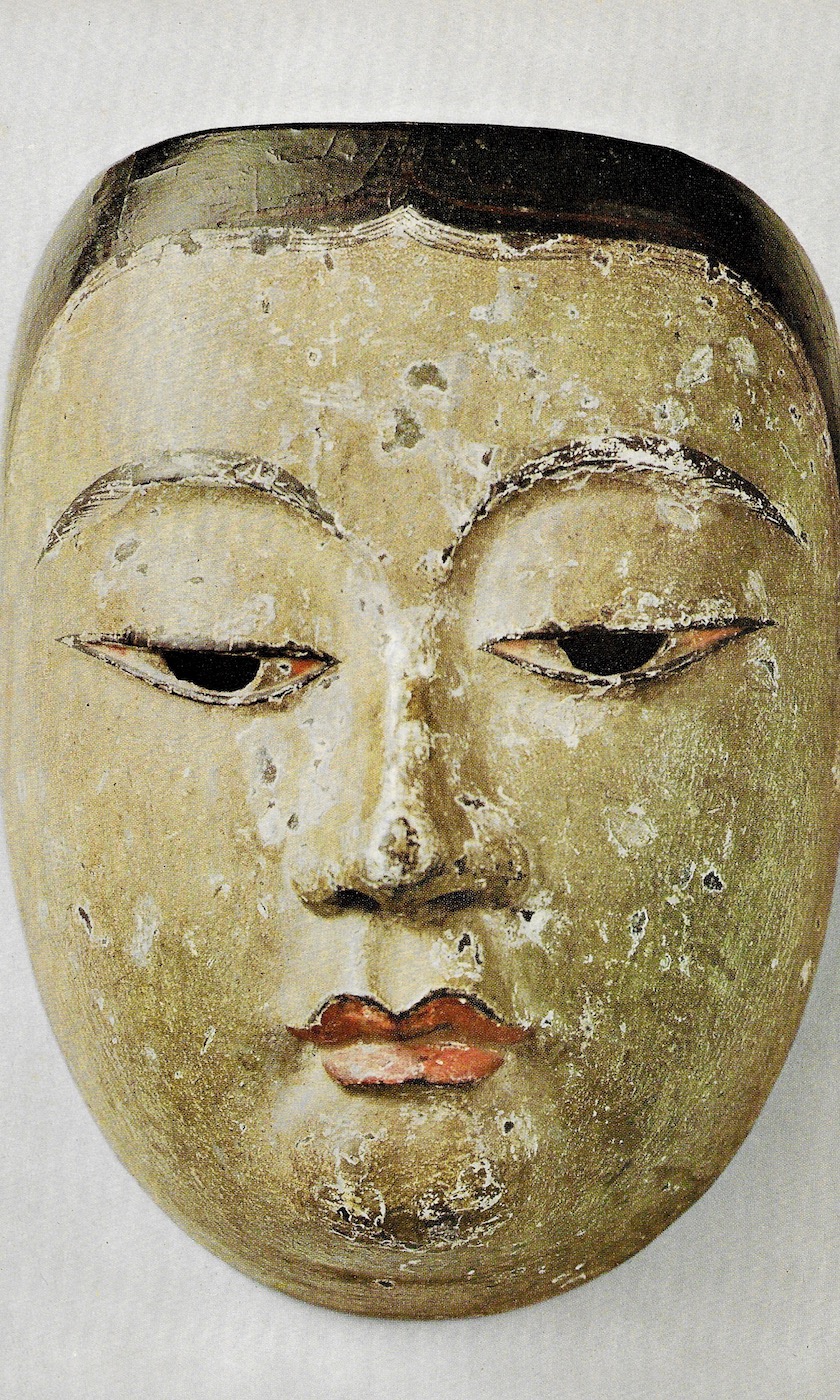

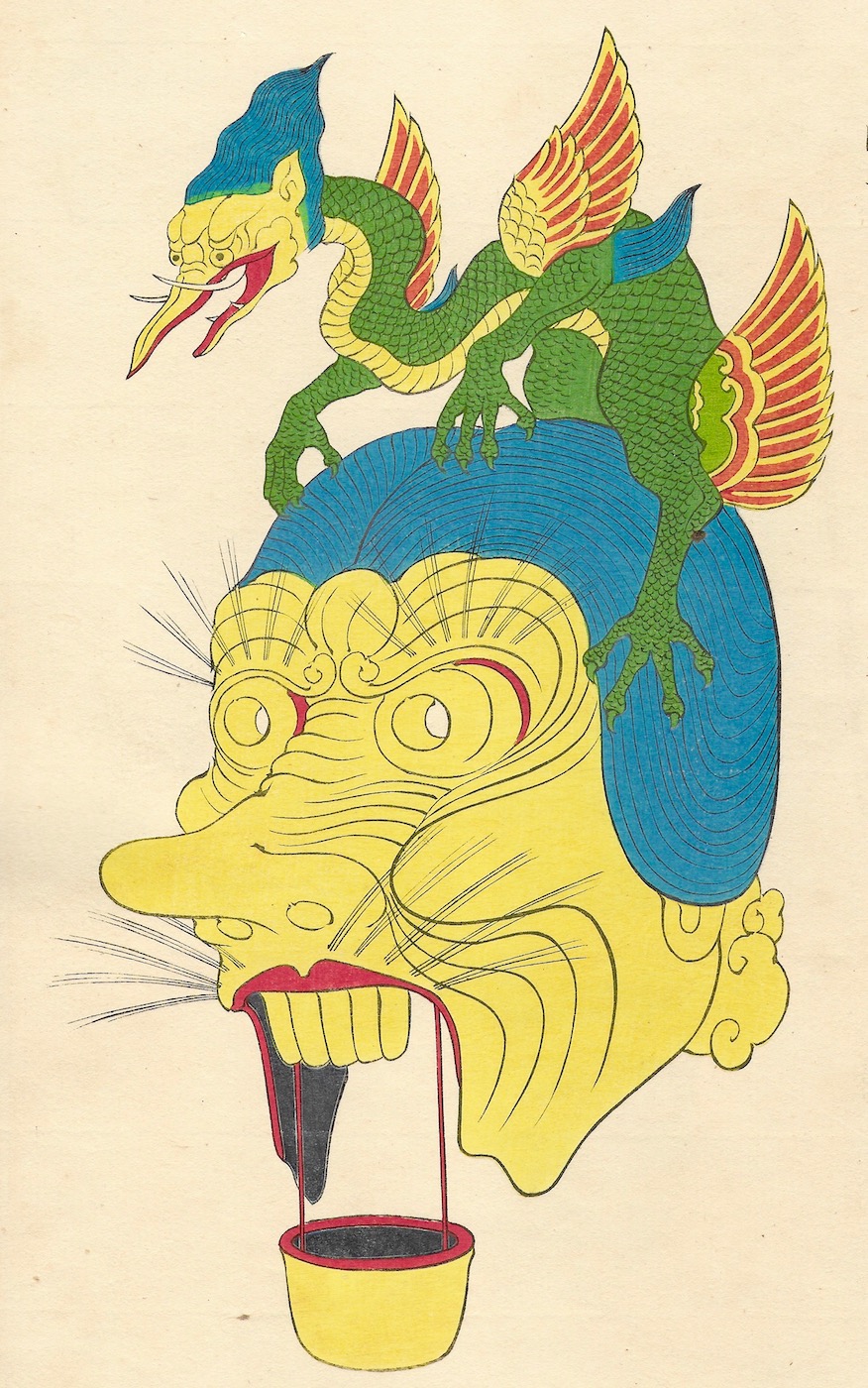

Similarities with Buddhist sculpture can be seen in this mask.

Image courtesy of Sumiyoshi Shrine and the Japanese

Ministry of Cultural Affairs

It makes a kind of primordial sense that dances from high antiquity should find a lasting home as a Shinto art in the kami worship of Japanese gods, a type of natural and archaic divinity—dances from legendary Chinese warrior kings and mythological natural rulers who “seized the blooming plum branch and declared rulership;” from large bird creatures with human heads called karyobinga, whose voice is the Buddha’s Law; and from ceremonies to immortalize and memorialize proto-human accomplishments such as Ancestor Yu’s controlling the floods. A first century dirge for the young prince Yamato Takeru (c.72–c. 114) is the basis for a dance still performed today.

years old, from the Heian court, eighth century, Japan. Published

in Gagaku, Weatherhill, New York and Tokyo, 1971.

Image courtesy of the imperial household

Bugaku is a dance of the gods, an entertainment meant to please and delight the most ancient powers, and to lend stabilizing order to society. Such dance is intended to instill and model divine design.

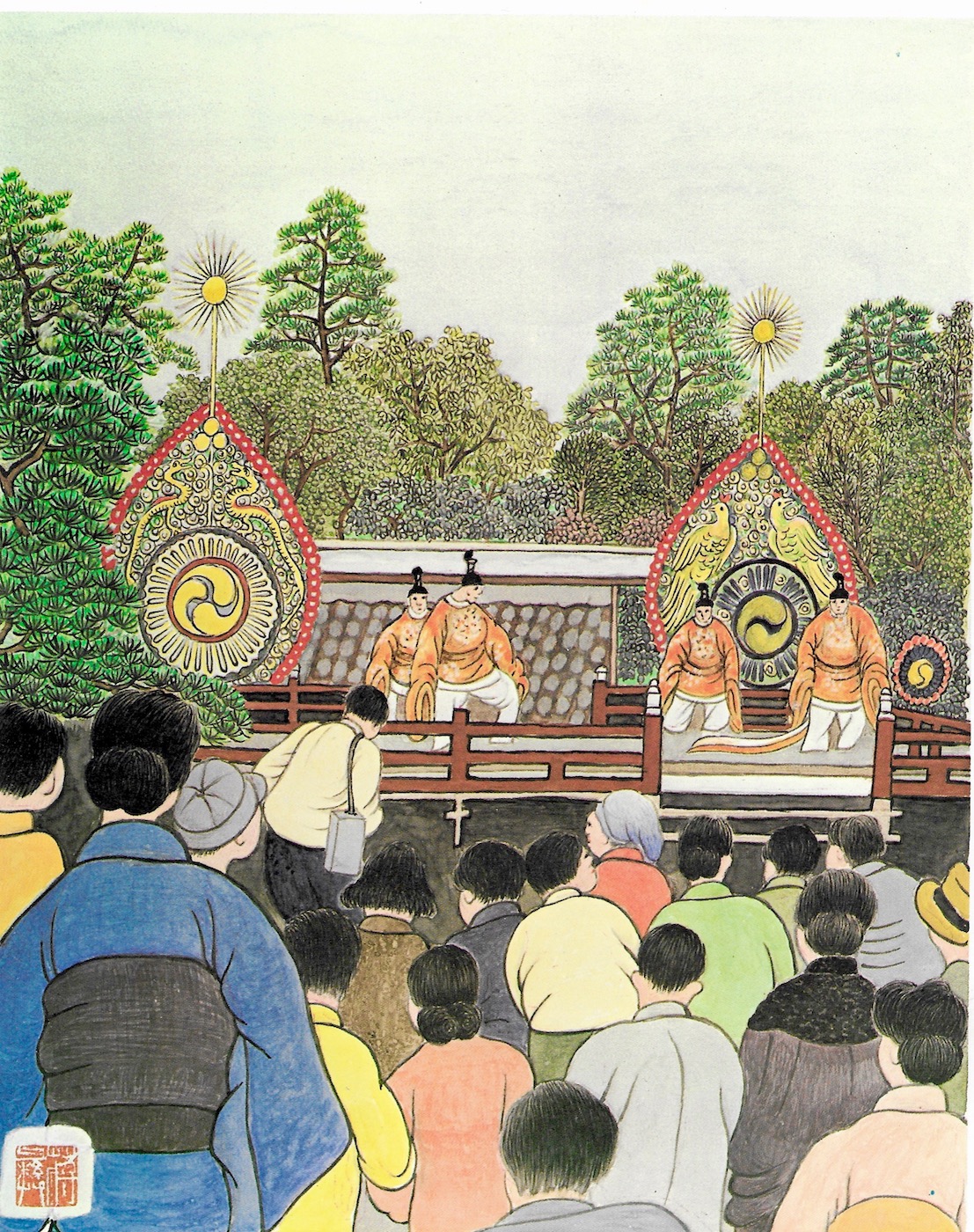

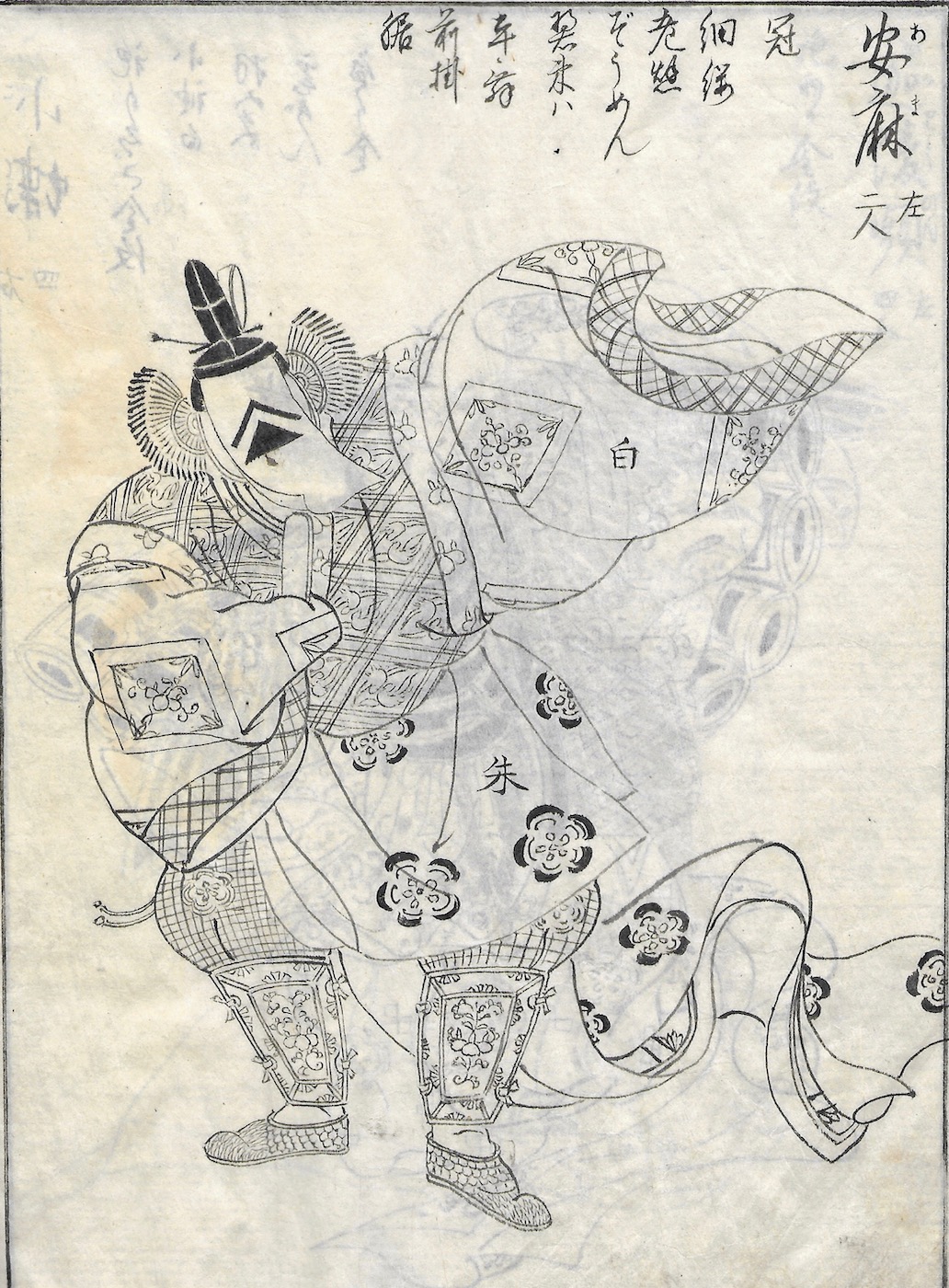

the emperor, most recently in 2019 with the ascension of

Emperor Naruhito to the Chrysanthemum Throne. From an

Edo period woodblock print book, private collection.

Image courtesy of Core of Culture

Sacred animals danced along lines of astronomical geomancy, assuring cosmic order. Plain, great men revered the subtle cycles of nature, and mirrored their order and succession. Soldiers, having mastered their martial arts, made formations to honor the character of their ancestor legends. Such were dances of bugaku.

book, private collection. Image courtesy of Core of Culture

Bugaku is not an act of appeasing a god or fear of a divine power, but a spiritual act of love and light, of order and harmony: Kami no asobi—the play of the gods. In fact, with bugaku established as the court dance of Japanese emperors since the Heian era in the eighth century (continuing even today), and that royal lineage being direct descendants of the Sun itself, bugaku can be called Dances in Honor of the Sun Origin.

Watercolor painting by Chiang Yee, 1971, reproduced in

The Silent Traveler in Japan, Norton Books, 1972

Human ritual does not get much more primal than that. This solemnity of seasonal rites, of origins, and cosmological significance is retained in bugaku today; a dance with no narrative aspect, no drama, no plot—only beauty, antiquity, order, dignity, and fundamentality. Each dance has a hoary archaic identity and true-life source, here made vital in exacting ritual evocation. There is nothing mimetic in the movements. Energy runs in straight lines. Bugaku is the universe speaking clearly.

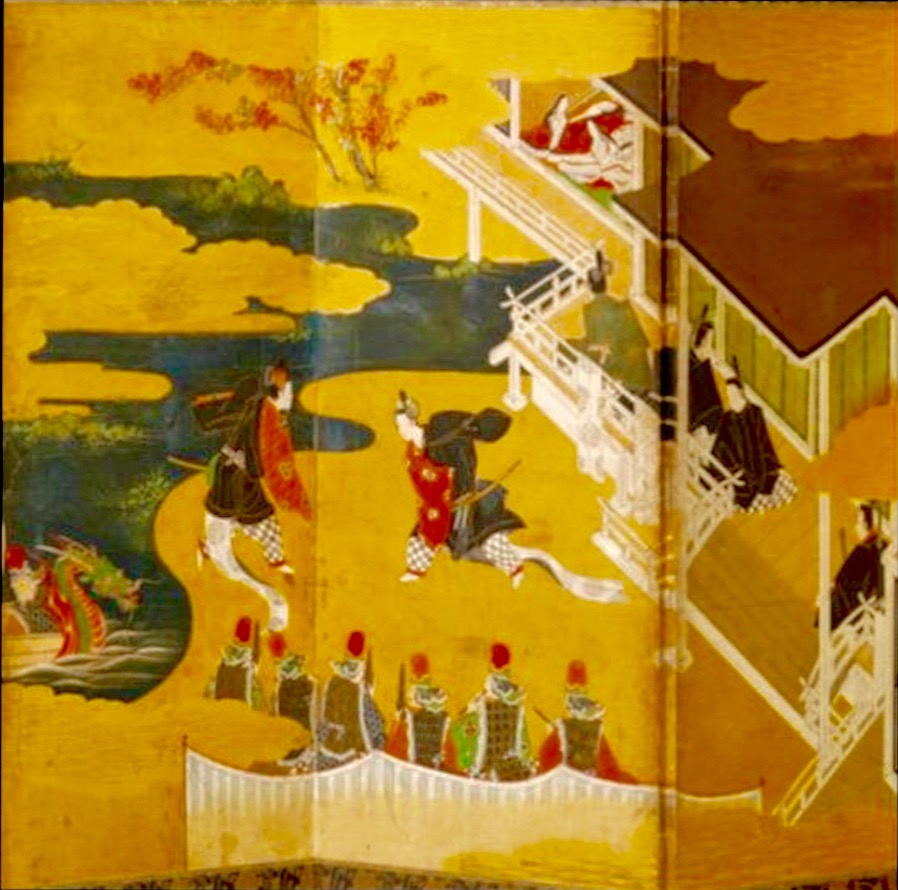

Depicted: Korobose, left, Genjoraku, above right, and Ryo-o, below right. Image courtesy of Daigo-ji

The story of bugaku’s arising is complex and fascinating, and demonstrates dance’s ability to carry ambiguous, mysterious, and contrary forces along with it. It can be reduced to comprehensible factors set out here. Japan’s Imperial Nara period (710–94) was a golden age of Buddhism in Japan, importing many elements from Tang dynasty (618–690 and 705–907) China, including various schools of Buddhism, architecture, Confucian political structure, and many dances from as far away as Persia, India, Siberia, Mongolia, Tibet, Vietnam, and several prosperous kingdoms that make up modern Korea.

At the terminus of the Silk Road, the cave grottoes at Dunhuang, built continually from the fourth to the 14th centuries, provide a veritable Rosetta Stone of non-Chinese dances immortalized in distinctly Chinese and encyclopedic grandeur. These were wild dances, spinning dances, and worshipful dances; slave dances, mystical dances, and exotic dances; religious dances and dances denoting high stature and accomplishment.

Over time, they became, on the walls of the caves, imaginary otherworldly Buddhist dances performed by sometimes flying creatures that, in turn, reflected and influenced actual dances being shown and shared for more than a thousand years. It is a rule of thumb for Buddhist art that dances depicted are actual dances that existed before the art. China has recorded dances since the dawn of time, organized them, Sinocized them, and combined them.

private collection. The figurative dragon atop the mask is a marker

of antiquity and a model for abstract stylizations of headgear to follow.

Image courtesy of Core of Culture

Gigaku, an extinct Asian dance imported into Japan in the sixth century, was a dance performed in front of Buddhist images from central China. It offered a smorgasbord of pan-Asian cultures . . . and faces, as reflected in the extant masks: big noses, white skin, curly hair, wide eyes. Old Buddhist dances from early Theravada times were not monastic or ritual dances, and often veered into the lewd and humorous. China’s tendency to produce variety performances, as evidenced in its earliest histories, accentuated the spectacular and impressive, even if the quality on display was delicacy. Dance was popular, collectible, exotic, and accompanied every religious and, later, civil ceremony.

The Chinese Tang court (618–907) opted for those Buddhist-informed dances from India, Tibet, and Mongolia, ritualized and noble, and tempered them further with Confucian ideals of discipline, harmony, and propriety. In Japan, the arch-elegant Heian court (794–1185), whose aesthetic ideals are so commonly associated with Japan—essentialism, understated glamor, and exquisite refinement—were applied to proto-bugaku dances arriving in Japan, to transform them into distinctly Japanese cultural expressions. Although officially a Shinto art, bugaku masks were crafted by leading sculptors who specialized in carving Buddhist images.

Edo period, private collection. Image courtesy of Core of Culture

The costumes of bugaku owe as much to the Heian court as they do to Tang China, and their places of origin and assimilation. Thanks to the compassionate cultural behavior of Buddhism over the centuries, ancient powers were honored and included in their true nature, however stylized and adopted. Imagine—what we know of Tibetan monastic dance is that it assimilates pre-Buddhist magic and deities. This in turn, influenced Chinese Tang court dances, which assimilated the Tibetan dances and others with a Confucian refinement.

These dances were then imported into Japan, where they survived after dying out in China with the end of the Tang court in 907, and became something even more composite, cosmopolitan, and Japanese. At the same time, this increasing complexity was honed with incredible distillation, clarity, and immortalization. Bugaku exists and survives thanks to several cultural propensities across Asia to organize, codify, memorialize, and revere dances. Bugaku is the ultimate expression of Asia’s awe and respect for dance.

The Cleveland Museum of Art and its curators Sinead Vilbar and Kevin Gray Carr produced in 2019, a once-in-a-lifetime exhibition of Shinto arts, to be shown nowhere else in the world, not even Japan. Among the many treasures were 17th century bugaku screens, displaying with Japanese decorative splendor, 24 different bugaku dances. Bugaku enjoyed a revival in the Edo period (1603–1868) and was even a rage. There are extant woodblock print books of Edo period bugaku dancers and several of the images accompanying this article are good examples from private collections.*

Many artists depicted bugaku, and among them the great Kano family vaunted bugaku into artistic eternity: two six-panel screens, enormous; gorgeous figures showing 24 distinct bugaku dances. It is composed of rare and rich pigments, placed on a gravity-free field of shining gold—as if an entire days’ program of bugaku was appearing at once—floating in a timeless radiance. It is dance documentation; it is high art. It is a cultural offering possible only due to the entirety of archaic Asian dance worship, and a pervasive, unbroken cultural reverence, finding a home as a quintessential Japanese cultural perfection.

Bugaku is enjoying a revival in popularity today as dance scholarship enriches attention, purity of immortalization is admired, and its transporting music gagaku—the art of which it is a part—gains new admirers. There are more than 100 extant bugaku dances, and one wonders how these 24 dances were chosen by Kano Eino more than 400 years ago? All 24 depicted dances are still performed today.

Of course, bugaku’s fortunes ebbed and flowed depending on whether a Shinto emperor, concerned with life, or a Buddhist shogun, concerned with fighting and death, (and so favoring Noh), was in power. But every military ruler understood the value of gagaku and bugaku, and in various ways always preserved a place for it. Aristocrats, both courtly and military, studied and sponsored bugaku. There is something undeniable in the ancient powers that vibrate in the music and move in the dance: Dances of the Right (komagaku, from Korea and beyond); Dances of the Left (tomagaku, from China).

It is a divine breath, an Earth and Sun-sanctioned function reserved for the most solemn occasions. With bugaku came the rhythm known as “jo-ha-kyu.” The late singer David Bowie called this perennial accelerative pattern, “found rhythm, variable time flow.” Like a fractal pattern—apparent in the smallest and largest expressions of the form—jo-ha-kyu is an organic pulse. It is described in different ways. “Introduction, faster, breaking,” like a wave. “Pattern, development, rupture,” like a dynasty. Jo-ha-kyu came to define Noh theater and other forms of rarified Japanese performance. There is no steady rhythm, rather there is the organic primordial pulse of thousands of years that carries the most ancient for us still.

Image courtesy of the Neo-Classic Dance Company, Taiwan

Murasaki Shikibu, a Heian noblewoman, wrote the world’s first novel, The Tale of Genji around 1000 CE, telling of the times and her love, the illustrious Prince Genji of the Minamoto clan. To conclude this brief appreciation of the ancient dance, please enjoy reading as she describes Prince Genji dancing Bugaku:

Prince Genji danced “The Waves of the Blue Sea.” There was a wonderful moment when the rays of the setting sun fell upon him and the music grew suddenly louder. Never had the onlookers seen feet tread so delicately nor head so exquisitely; and in the song that followed the first movement of the dance his voice was as sweet as the Kalavinka’s whose music is the Buddha’s law. So moving and beautiful was this dance that at the end of it the emperor’s eyes were wet, and all the princes and great gentlemen wept aloud. When the song was over and, straightening his long dancer’s sleeves, he stood waiting for the music to begin again and at last the more lively tune of the second movement struck up—then indeed, with his flushed and eager face, he merited more than ever his name of Genji, The Shining One. (Murasaki Shikibu, The Tale of Genji, p. 129. Translated by Arthur Waley in 1935.)

mid-16th century, artist unknown. Image courtesy of Cincinnati Art Museum

* On the Autumn Equinox, 21 September, at 7:30pm, the Japan Society in New York City will present Reigakusha: Gagaku and Bugaku, an evening of Gagaku music ancient and modern and featuring a Bugaku dance performance.

See more

* On the Autumn Equinox, 21 September, at 7:30pm, the Japan Society in New York City will present Reigakusha: Gagaku and Bugaku, an evening of Gagaku music ancient and modern and featuring a Bugaku dance performance.

See more