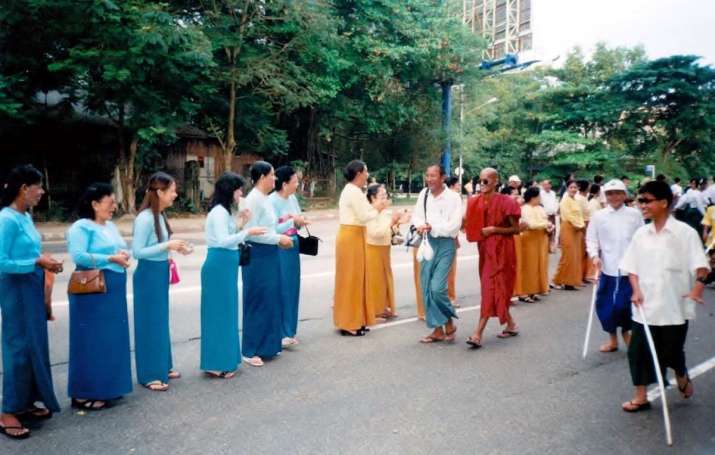

The Sun has barely opened its eye on this October morning in Myanmar, but already there’s a buzz of activity at the School for the Needy Blind as the bus pulls up into the compound. With a giggle, 15-year-old Phyo deftly dabs a light shade of pink onto her lips. She is determined to look her best for this special day. Tapping her cane along the way, she finds the steps of the bus and mounts confidently. For Phyo, and many of her excited classmates on board, this is their first International White Cane Day march in Mandalay.

“The students have been looking forward to this,” remarked Sayadaw U Nye Ya, founder of the School for the Needy Blind in Pyin Oo Lwin, a hill station town about two hours’ drive from Mandalay. “International White Cane Day on 15 October is a special day for the blind community. The white cane is a symbol of independence and safety for the blind. It allows them to perform simple everyday tasks on their own without relying on others. Today we celebrate the independence and self-sufficiency of blind people, and also honor the contributions made by people who are blind or visually impaired all over the world.”

The 71-year-old monk knows only too well the difficulties and suffering of the blind and visually impaired. Born in Shwebo Township in Sagaing Division, Sayadaw lost his eyesight at age three after contracting small pox and measles. Despite his handicap, he was ordained as a samanera at a monastery in his village, learning Pali and Buddhism by listening and memorizing. In 1967, he left the monastery and joined the All Myanmar School for the Blind in Pakoku, where he learned braille, mathematics, astrology, and Myanmar orchestral music. Thereafter, he started a small business and led a comfortable, independent life. He even formed a music band called Cho Tay Yin with some of his fellow students. But in 1981, he took on the robes once again, making good use of his time to study the Patimokkha* and Sanghaha Pali in Braille.

Determined to help those like himself, and to change social prejudices toward the blind by showing that they can learn and live meaningful lives just like anyone else, Sayadaw founded the School for the Needy Blind in 1991 in Shwebo. With the generous support of donors, the school relocated to its present location at the foot of the Mount Suthtukanthar Sudaungpyae Pagoda in Pyin Oo Lwin in 2001.

Despite recognition of the need for inclusive education in Myanmar, there are few facilities or opportunities for the blind and visually impaired in Myanmar, especially in rural areas. A child who is blind or disabled in a rural village is often unable to find a place in mainstream public schools. Even if they are lucky enough to be enrolled, it is still a big challenge as these schools are not equipped for the blind.

The School for the Needy Blind is home to about 130 resident students—45 females and 85 males (including a handful of monks)—of different ages who are completely or partially blind. Some of the children are orphans while others have families who are unable or unwilling to care for them.

“Life for the blind in Myanmar is not easy. Blind people face many social and physical barriers in schools, in public spaces, and in their social life,” said Daw Sitagu, who has been helping out at the school since it started. “Many dare not go into the community or to school. They are often stigmatized and seen as unproductive and a burden to their families and society. Many come from poor backgrounds and parents themselves are uneducated, so they do not see the need for a blind child to go to school. But here, at the School for the Needy Blind, there is no discrimination or bullying. Everyone feels at home and is part of a big family.”

Run solely on donations from the local community, it is the second-largest school for the blind in Myanmar, with 20 teachers and two volunteers who attend to administrative and managerial matters. Besides residential care, there are classes for different levels in braille, Buddhist studies, English, mathematics, and other subjects. Because of the lack of career opportunities for the blind with formal education, the school provides specially tailored skills training, such as in bamboo crafts, astrology, and traditional massage—skills that will allow them to make a living when they leave.

There are also special classes in traditional Burmese and Western music. Since 1999, the school’s band, which comprises both traditional Burmese orchestral and Western instruments, has toured towns and villages to play at fundraising events and also at social and religious celebrations.

“Besides raising funds, I hope our performances can inspire other blind people, and change public attitudes towards disability,” said 17-year-old guitarist Ko, who aspires to be an English teacher. We want people to recognize that blind people can play as well as sighted bands. Even if we can’t see the audience, we are happy when we hear the clapping and cheering.”

Recognizing that the social, educational, and mobility challenges faced by the blind are shared by many handicapped people, Sayadaw started the country’s first independent training school for the blind and handicapped in Monywa in 2015. A joint project with the Japanese Association for Aid and Relief (AAR), an international NGO that has been present in Myanmar since 1999, the Monywa School for the Blind and Disabled is designed with special needs in mind, such as ramps for easy wheelchair access and handrails along the walkways to serve as guides for blind residents. Even personal wear is thoughtfully designed. Little Cherry, who lives at the home with her father at the Monywa school, wears shoes that squeak so he can monitor her whereabouts when she runs around the school compound.

The school is managed by Tet, who was born with spinal deformities, and a number of specially trained teachers.“There is a real need for training centers like the one in Monywa and for qualified teachers to provide equal opportunity and equal access for the disabled,” said Tet, expressing his appreciation for the school. “Public schools lack properly trained teachers and adequate classroom resources.”

Thoo, who teaches sewing, said his own experiences inspired him to teach vocational skills to others with disabilities. Born with one leg, no lower arms, and part of his jaw missing, Thoo suffered much frustration before coming to the home. “People stared at me like I was a freak. They didn’t understand my situation and I was so embarrassed I just stayed inside my home. When I came here I finally felt like I was an equal.”

community to support its operations

With the help of Sayadaw, Thoo managed to complete an AAR-sponsored tailoring course in Yangon. Happy to share his skills with others, Thoo adds: “I never dreamed I would be able to learn it, because I was a disabled person. But now I feel I can help others with disabilities to find some meaning in their lives.”

To date, about 70 students have graduated from the School for the Needy Blind. Three of Sayadaw’s students have obtained university degrees. Many are leading self-reliant lives, and some have married and started families of their own. Some, like Hlaing, who has a degree in psychology, have returned to teach at the school in Pyin Oo Lwin to help others realize their own dreams.

“Blind people used to think that they were blind because of their bad karma. They were resigned to their fate and did not think they could change their lives,” stresses Sayadaw U Nye Ya, proud of the achievements of the graduates from the School for the Needy Blind. “But the Buddha taught that even the blind can see the Dhamma, can have the chance to practice and improve their situation by doing good and being helpful to others. The blind themselves need to take responsibility for their own lives. These students are shining examples of how we can overcome our handicaps and strive for a better life. Life is not lost despite being blind, but life will be lost if we are not educated!”

All images courtesy of Sawaydaw U Nye Ya.

* In Theravada Buddhism, the Patimokkha is the basic code of 227 rules for fully ordained monks bhikkhus and 311 for nuns bhikkhunis.

See more

Pyin Oo Lwin Blind School (Facebook)