On 2 August last year, I was completely shocked to hear the news of the death of Cui Xiuwen. Just a few months earlier, we had enjoyed a great talk at her place in Beijing. She looked fine and like many people around her, I was convinced that she was recovering from her recent operation. So was Cui Xiuwen herself. She was already planning a new project and discussing collaboration with me.

As an artist, Cui Xiuwen had all the glamour. She was the first Chinese artist to be exhibited at Tate Britain. As one of four female artists who formed the Siren Art Studio in 1998, Cui Xiuwen will always be remembered in the world of contemporary Chinese art and the feminist movement. Throughout her career, she received many international awards as an artist and as an accomplished woman. Because of this, she was one of the most sought-after spokespersons for luxury brands from around the world.

She and I were 20 years apart in age. When we met, I was at a completely different stage of life. Although I had discovered my passion for Buddhist art, I was still experimenting with ways to express myself and trying to validate my existence. Having deviated from the academic and professional foundation I had built, I was wandering around the world quite aimlessly. Beyond the unstable life of working freelance and extensive travels for two years, I knew intuitively there was something greater out there, but I did not know what that was.

Buddhism brought Cui Xiuwen and I together. In March 2017, I was helping to organize an international conference on Faxian (337–422), a Chinese Buddhist monk who had embarked on a 15-year pilgrimage to Central and South Asia in his 60s. The conference was held in Faxian’s hometown of Xiangyuan, Shanxi Province, and preparations took place in the mountains at Mount Wutai International Institute at the Great Sage Monastery of Bamboo Grove.

Before I flew to Beijing to pick up two reputed Buddhologists from Europe in order to take them to Xiangyuan, I was introduced to Cui Xiuwen through a mutual friend. At the time, she was considering pursuing further studies in Buddhism in the UK. Upon learning about the coincidence, Cui Xiuwen suggested we have lunch at her place during our short transit in Beijing. In fact, it was the first time she had received guests following her operation. Even though she admitted that she still felt weak, she was glowing with beauty and strength. The lunch was delicately prepared by her maid, but our meeting was regrettably rushed. Just when the conversation began to warm up, we all had to leave for the airport.

Then life went on. I continued to explore, traveling from Turfan to Doha, from Bruges to Yogyakarta. Physical mobility elevated my spirit and gave me different perspectives. Sometimes I felt as if I could go anywhere, and that anything was possible. However, at one point, I felt my energies were scattered and sensed a lack of depth. I could spend my whole life trotting around the globe, but where would that take me? There was an urge within me to internalize these experiences and to build something solid.

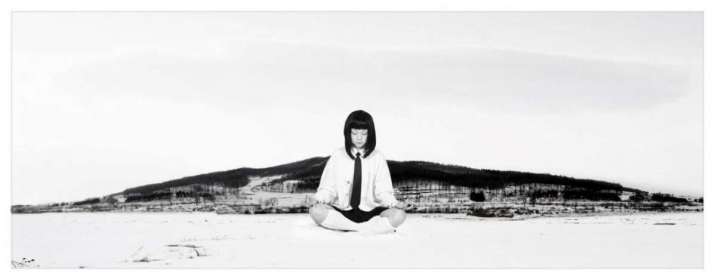

Fortuitously, around this time I met Cui Xiuwen again in Beijing. It was exactly a year after our previous meeting, in March 2018, and it was also for lunch at her place. Also, coincidentally, just as I was preparing to go to the airport. It turned out that she had not gone on to academic studies during convalescence, but instead had devoted much of her time to spiritual practices. She appeared world-weary and said that when she recovered, she would spend half of her time making art and the other half meditating. At the time, I could not possibly fathom how sitting with one’s legs crossed would lead to enlightenment. That was a practice I had not experienced, even though I had been studying Buddhism and Buddhist art.

Cui Xiuwen once said in an interview, “Buddhism continually guides my mind, and my life transcends to a higher elevation.” While Buddhism has become popular in the West and has been resurgent in the East, many contemporary artists are incorporating Buddhist imagery or concepts in their works without actually comprehending them. One rarely finds distinctively Buddhist elements in Cui Xiuwen’s works. However, to me, they are more Buddhist than many others because the artistic life of Cui Xiuwen was a persistent practice of Buddhism. In her own words: “What you do is not that important, what is important is whether what you do can help you to gain awakening and to enter another realm.”*

To Cui Xiuwen, art was not the ultimate goal. Rather, art was just a vehicle. She changed her medium from painting to video and photography because she realized that her thought developed faster than her painting techniques. Her earlier paintings and videos, including Ladies’ that made her name, were imbued with desires. However, her expression soon became softened and subtle, and toward the end of her life, even more abstract and transcendental. Cui Xiuwen’s works are often interpreted as exploring sexuality, humanity, and spirituality. Such progression resembles ascending the Trailokya, the three realms in Buddhist cosmology: the realm of desires, the realm of form, and the realm of formlessness.

As women, we also talked about love. Earlier in life, Cui Xiuwen used to admire female artists such as Isadora Duncan and Maria Callas, who were talented and in love. However, in our talk, she confided in me that she came to find romantic relationships meaningless, including her own marriage. She appeared much more joyful when she was showing me her Buddha Hall, where she had painted the ceiling with pure gold. In fact, the project we were discussing was to focus on “Women and Spirituality.” However, I was not sure whether she thought spirituality and womanhood contradicted each other at that point. When she saw me off and I was about to enter a taxi, I asked her, “Do you still believe in love?” She answered calmly, “Yes, but maybe that person is too far away, and maybe we will never meet.”

That was the last time that I saw Cui Xiuwen. We kept in touch and exchanged some ideas over the phone, but our project was never launched before her death. The time I spent with Cui Xiuwen was very short, but it had a profound impact on my life. I feel that the project we had discussed on women and spirituality is a legacy that she passed on to me, and I am entrusted to carry it forward.

Since then, I have become more and more engaged with Buddhist practices and rituals. Through meditation, I have had a glimpse of that conscious state of clarity, liberation, and bliss. My faith has been constantly reinforced by meeting extraordinary practitioners around the world: the meditation monk at Drak Yerpa in Lhasa, the mountain yogi wandering around the Himalayas, and the Buddhist nun who spreads the Dharma in the West. Meanwhile, I wonder: if the path to enlightenment requires diminishing emotional entanglements and mundane concerns, where is the place of womanhood in spirituality? Does one become a woman, as termed by Simone de Beauvoir, or should one strive to overcome womanhood?

With all of these questions, my journey continues. Just as Cui Xiuwen described her relationship with Buddhism as “following the light,” I have “opened one door after another.” I experience life and death in every second. Let us see where all these take me . . .

* Yishu Interviews Cui Xiuwen (YouTube)