Ron Epstein, PhD, is a founding member of Dharma Realm Buddhist University and retired lecturer emeritus in the philosophy department of San Francisco State University. He earned a BA at Harvard University and a doctorate at the University of California, Berkeley. Epstein commenced his lifelong study and practice of Buddhism at the age of 24 under the guidance of Tripitaka Master Hsuan Hua. His contributions to Buddhist scholarship include his work as a principal translator of the Surangama Sutra, an important primer on Buddhist meditation. He has written extensively on the contemporary application of Buddhism and Buddhist ethics, and also co-sponsored legislation that banned for the first time the growing use of GMOs in Northern California on a county-wide basis.

This month, I interviewed Dr. Epstein on his new book Responsible Living: Explorations in Applied Buddhist Ethics—Animals, Environment, GMOs, Digital Media.

Buddhistdoor Global: What really caught my eye with your book was the intersection of your themes with Buddhist ethics. To start off with, could you talk a little about the legislation you introduced banning GMOs.

Ronald Epstein: Yes. I and a couple of friends started working on Local County Measure H to ban growing and raising genetically modified plants and animals. We started in 2003 and it was on the ballot in 2004. I had actually become interested in this issue in the early 1990s. I tried very hard to get people interested in it over the years and had pretty much given up when some friends called me up and said, “Do you want to put this on the ballot with us?” And so I was very pleasantly surprised. It was quite a ride—the first time for banning GMOs in the country on a county level.

BDG: No US states at that time had banned GMOs at the state-wide level. Do other people working on similar legislation now come to you for advice?

RE: Not recently. It’s a very good question you ask. I think that people are so confused by the technicalities at the research level that it really takes some study into what’s going on in the field from a scientific perspective to understand what needs to be done at the legislative level. That’s one thing and, frankly, most of the key players here who worked on it back in 2003 are now in their 70s or even 80s and there hasn’t been a lot of interest directed our way from younger generations. I’m still hopeful that people will look into these things because there is, of course, a lot at stake.

BDG: Are you still doing courses on Buddhist ethics?

RE: I’m pretty much retired from teaching now. I was teaching first at University of California at Davis and, for a much longer period of time, at San Francisco State University. I’ve been involved for many decades with Dharma Realm Buddhist University (DRBU), which is a very small, fully accredited Buddhist institution. When I was teaching at San Francisco State University, the university began an initiative in teaching environmental studies. I suggested that they have one course in environmental ethics as part of the requirements for the major, but nobody was interested. It was very strange. Initially I thought, this is terrific, we’re doing environmental studies and then I found out that what they were primarily interested in was helping people get jobs with big corporations that wanted to justify their anti-environmental actions.

BDG: Well, you are a pioneer in this area because look at what’s happening with all these widespread environmental youth movements. Maybe that gives you some sense of hope when you see how these youth movements have picked up, very recently becoming a tremendous force. I would think that there are now children in middle and elementary school who are to some degree very interested in environmental ethics. It is becoming more of a mainstream point of dialogue.

RE: Yes, absolutely. I’ve been really encouraged by that and from my perspective that’s the most encouraging thing that’s going on in this area—the young people. I hope they keep it up. When they were putting together the environmental studies program, I made a compromise with them and with my department (the philosophy department) that they would include an environmental ethics course if I were willing to put it together and teach it. Nobody else was interested in doing it at all, so they gave me a blank slate. I had never taken a course in environmental ethics so it was a really interesting exploration for me, and I got a really positive response from the students.

BDG: That’s wonderful. Looking also at how technology-dependent we are, do you have any thoughts on developing such ethics alongside the awareness of our technology use, as well as bringing in Buddhist philosophy to help reconcile and change what we need to do?

RE: Yes, it is very broad, but I think we also need to look at the big picture. I’m in a pretty isolated community in Northern California. From time to time I really wonder if I’m in tune with the situation, for example in Silicon Valley. Not too long ago I met some younger people who had influential positions in Silicon Valley firms and had started ethics discussion groups in their corporations. And so we all got together on a conference call, several of these young people and myself, to talk about and think about what was going on on the ground.

On the one hand, it was wonderful that their corporations were supporting them to have these little discussion groups taking up the issues. But then on the other, when we talked further it became clear that these corporations were willing to do so as long as it didn’t rock the boat and affect corporate profits. But just the fact that people continue to bring these things up is a good sign. I’m always impressed by people who voluntarily lose their jobs for their principles.

BDG: Plant-based or vegan meat and dairy replacement products are popular in Silicon Valley. It is not likely that the people running these businesses are doing so because they are Buddhist, but rather they see there is a market and they are looking for cleaner technologies to replace the problematic model of factory farming. They see the present and the fact that this is not sustainable and so they work to come up with viable and profitable solutions. In your book you chose to focus on morality and high-tech genetic engineering, and a range of issues within digital and social media use. Why did you choose to focus on these specific areas of technology?

RE: I think one of the main problems is that if we look historically at the development of Buddhism in the West in the early 20th century, the expedient that the early European Buddhists used was that, unlike Christianity, which was anti-science and anti-evolution, Buddhism was presented as pro-science, entirely compatible with science, and even scientific in its own right. This was a kind of expedient means for drawing people’s interest to Buddhism. I think most people who have any idea with what is going on with Buddhism in the West today know that. For instance, one can see that for the last several decades, His Holiness the Dalai Lama has been doing the same type of thing and has been meeting with all sorts of scientists and academics—one group each and every year, year after year—and using this as a kind of expedient means to get people interested in Buddhism.

But I think we may have gone a little bit too far in that direction and we need, from a Buddhist point of view, to do a critique of science and scientism. I do have one essay in my book about Buddhism and science, and one of the main points I try to make is that science is interested in objectivity and only looks at the material world, and Buddhism is more interested in mental clarity and is not only looking at the material world but is also looking at the world of consciousness. If we start not only looking at the similarities of Buddhist teachings and science but also the differences, then some very interesting things will come forth.

Secondly, I think that my generation in the 1960s was interested in ethics in terms of social justice. It is obvious that it was a good thing to do, and the social justice movement is alive and well. Every generation has its own issues within it. But there’s been a neglect of personal ethics, of virtue, of character, and that is where I think Buddhism can make a real contribution.

Unfortunately, because there isn’t much popular study of Buddhist ethics among most of the Buddhist groups in the West, there isn’t a clear focus on what the prerequisites for developing this aspect of ethics would be. That’s one of the reasons I wrote the book—to not only bring to bear social justice issues but also issues of personal character, and how those interface with environmentalism or technology. For example, you noticed how much emphasis I put on the problem of empathy and the negative influence of technology in the development of empathy in children for example (from their digital device use). I think we need a lot more exploration of these kinds of issues.

BDG: Where do you see some exploration and addressing of Buddhist ethics in the context of contemporary issues beginning to flourish in the West?

RE: That’s a good question. Yes, there’s a lot of potential there (in universities) but also in some of the monastic communities that are paying more attention to the ethical basis, in terms of what I like to call karma-based ethics. There’s tremendous potential for some of the more traditional Buddhist communities, particularly monks and nuns, to play a very important advisory and modeling role in this.

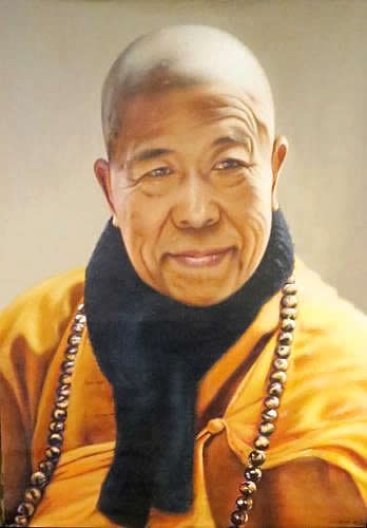

I want to call your attention to the foreword in my book written by Venerable Ajahn Pasanno. He is part of the Thai Forest tradition of Ajahn Chah. They have a monastery just about half an hour north of us. He has done really remarkable work both in Thailand and here in the US on major environmental issues.

Of course, it’s not only happening at Buddhist monastic institutions. I have a friend, Reverend Heng Sure, who went on a three-steps-one-bow pilgrimage for world peace. He’s a senior monastic in the Dharma Realm Buddhist Association and is very active at interfaith events. He allowed me to tag along a year to a monastic conference at Thomas Merton’s monastery in Kentucky. There was a retreat there of monastics from all different religious traditions to talk about what their monastic communities were doing in terms of preserving the environment. So I was very pleased that I had an opportunity to participate and learn from all these monastics. This was more than 10 years ago and they already had a very sophisticated approach to these issues. I think there’s potential there.

BDG: On page 52 of your book, you note: “Our greatest slow-boil threat may be one you may not even know about—the radical decline of empathy due to social media. Buddhism teaches that our personal problems and the problems of the world are best solved through the application of great compassion. It is our most powerful tool for ending human suffering.” Can you share more about this concern for the effect of digital media on our capacity to develop and cultivate compassion?

RE: I think we have to constantly keep in mind the balance of the potential benefits of these media versus the potential harms of technology. For example, the Buddhist Text Translation Society, which published my book, is very active in various parts of the world spreading the Buddhist teachings online. They’ve reached hundreds of thousands, perhaps even millions, of people in the West and in Asia. There are tremendous numbers of people whose entry into the Dharma has been via the Internet.

But the danger with the digital world is that it only treats “big data” as real, if that makes any sense. Anything that does not fit into the category of the digital description is not considered to be real. The problem is that if you only admit things that can be digitally described are real, then that leaves out everything that is of importance in Buddhism, starting with ethics. We somehow have to make sure that we don’t mistake digital descriptions for awakened mind.

My own Buddhist teacher, the late Venerable Master Hsuan Hua, said to use the mental states of the Four Pure Abodes, also called the brahma-viharas, as a kind of test to see whether or not we’ve gotten off track: loving-kindness (metta), compassion (karuna), sympathetic joy (mudita), and equanimity (upekkha). So I think if we use these four aspects of the Buddhist teaching and practice to see if what’s going on in digital Buddhism is measuring up to those four standards, then maybe we’ll be okay.

BDG: Going back to the inspiration for the book as a whole. You’ve addressed what compelled you to write this book earlier in our conversation; did you find while you were writing that it felt like a pioneering work or were you already familiar with a whole body of texts about the environment, technology, and Buddhist ethics?

RE: What the book is made up of, for the most part, are very lightly edited versions of talks I have given to various audiences over the years, from about 1990–2017. The way the book came about was that some Buddhist nuns who were interested in some of these issues and heard some of my talks, encouraged me to publish them so that they would reach a larger audience. They volunteered to do most of the work, and I was so moved and grateful that I thought, “If they’re willing to do all of this then how can I not go along and do what I can do get this book out.”

BDG: On page 34, you write that in terms of viewing the environmental crisis from a spiritual perspective: “The situation does not seem very encouraging, primarily for three main reasons. One, it is very difficult to change course at this point. In Buddhist terms, the karma is too heavy. Two, most people don’t seem to realize the seriousness of the situation; and three, that there is very little indication that we will fix the problems in time or that there is even much consensus of view about what needs to be done.”

I think about what you wrote, the emerging youth movements, and the fact that I am a mother in my 40s to two young children. This affects my view of the current ecological crisis and supports an inclination to learn about potential solutions. But I think it is important to recognize that, as you note: “the karma is too heavy.” It feels critical to have this as a base awareness, to know that there is a lot of work to be done.

RE: Let me share a personal experience with you. I was really happy to learn that you’re involved in the vegan movement and have interest in that. I have a son who is now 35, and when he was in elementary school, I took him to a place a few hours away in Northern California called Farm Sanctuary. The person who had donated the land for that sanctuary was a computer science professor at San Francisco State University who put on an international animal rights conference at SFSU in 1990, and she invited me to give a paper about animal rights and Buddhism. That was really the first time that it occurred to me that maybe there was something more people were getting interested in and I should do more in this area.

I decided to take my son, who was in elementary school at the time, to Farm Sanctuary. I was feeling pretty smug as a long time vegetarian when I went. One of the volunteers who took us around asked us if we were vegans or not and we said “No, vegetarians, not vegans.” She proceeded to educate us about the causes and conditions by which the dairy industry causes untold suffering. She asked us whether we were aware that when we ate dairy we were supporting the routine killing of male calves. That really hit me right in the gut. The visit had a big impact on my son, but it probably had, to my great surprise, a bigger impact on me.

BDG: That is quite profound to have been exposed to that awareness in the early 1990s. Of course, we know that the consumption of mainly plant-based diets is nothing new or “modern” for humans, but this aspect of veganism as a movement is really pretty recent.

RE: Yes. Earlier on in our Buddhist communities, our teachers had really emphasized doing “Liberating Living Beings Ceremonies.” There is a lot of controversy in Asia about how they do it. The basic idea is that people go and get live animals that are about to be killed (usually for food), buy them and release them. So this is part of my Buddhist experience. There’s the practical aspect of what’s involved in doing that—doing it in a good and environmentally proper way is a big challenge. We also need to look at the wholesale killing of animals from a Buddhist perspective. From a traditional Buddhist point of view, you have literally billions of animals being killed and in their intermediate life suffering greatly and being very angry. So we’re talking about a cloud of killing karma over the entire planet that’s affecting everything we do. So I really think that Buddhist teachers need to emphasize this aspect of Buddhist teaching more.

A lot is happening, particularly within the Tibetan Buddhist world, which has been very much identified with meat. I think they’re making some important in-roads in the direction of vegetarianism and veganism in their monasteries and communities. Chinese Buddhism has pretty much always been vegan.

BDG: I am definitely looking forward to learning more about how practices have changed at these centers over recent decades.

RE: Let me share a quick story with you. When I graduated from college, I came out to the West Coast. It was one of the few places in 1965 where they were teaching Buddhist meditation, which I wanted to find out more about. I found the teacher who would become my master, Ven. Master Hsuan Hua, a Buddhist monk from China. I started meditating with him, but I really didn’t know anything about Buddhism except for my own direct meditative experiences. After meditating with him for five or six months, I realized he was really a quite remarkable monk, totally without any sense of self, and it was this big realization for me. Soon afterward, when I was sitting on the steps of the building where he was living, he came outside and for the first time gave me some information about Buddhist teachings. It was a little bilingual pamphlet in English and Chinese: Why you should become a vegan.