If you aspire to lighten the burden of the world, to bring humanity a little nearer to the peace it craves—start right at home, and strive to free, to ennoble, to purify yourself, your own life, your own heart’s aspiration. — Allan Bennett

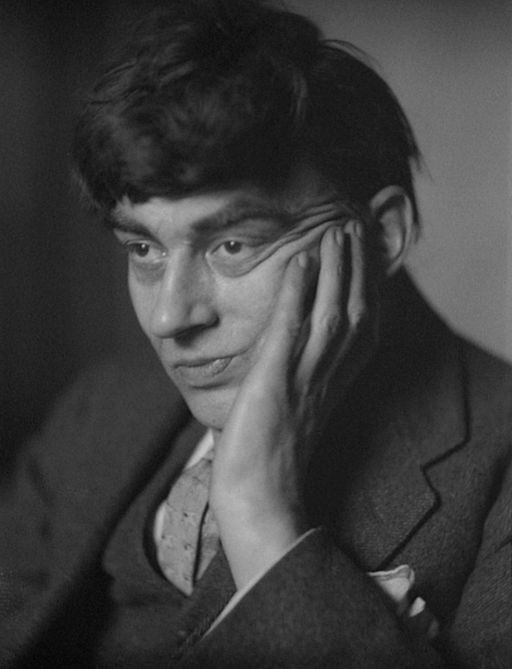

Although he died at the young age of 50, was in poor health, lived in desperate poverty, and remained largely unknown in his own country, Allan Bennett was England’s first Buddhist emissary and planted the seeds from which Buddhist centers would grow and flourish in the decades after his death.

Born in London on 8 December 1872, he was named Charles Henry Allan Bennett but dropped the first two names. As a youth he dismissed Christianity because it seemed incompatible with science and because he could not see the Christian God of love in the suffering he saw around him and the suffering he experienced in his own life. Bennett struggled increasingly with severe asthma, which often confined him to bed for days and weeks at a time. In school, he studied science, specializing in the areas of chemistry and electrical engineering. Spiritually curious and a seeker, Bennett began reading intensively, studying Hindu and Buddhist texts, and being drawn more and more to Buddhism. Of the Buddha, Bennett said: “I did not fully realize the colossal stature of that sacred spirit; but I was instantly aware that this man could teach me more in a month than anyone else in five years.” Later, when describing the life of the Buddha, he would compare the Buddha to the power of the Sun: “Buddhahood consists not in His humanity, but rather in the fact that, through incredible effort and endurance, he has attained to a spiritual evolution which renders him as different from a human being as the Sun is different from one of its servant planets. . . . His teaching [was] a focal center of spiritual power no less mighty in its sphere than that of the Sun in the material realm.”

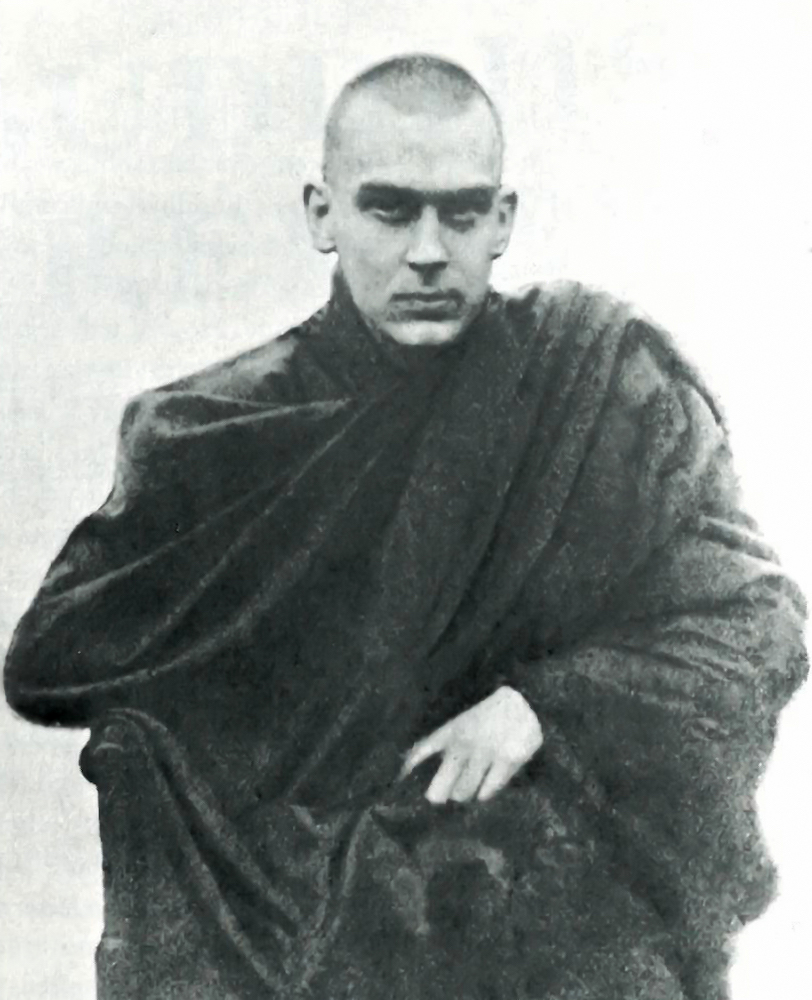

Pursuing his growing interest in Buddhism, Bennett sailed to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1900, eventually ending up in Burma (Myanmar), where he studied Buddhist texts in their original Pali language. After six months, one of his contemporaries wrote, he could “converse fluently in that sacred tongue.” A year later, Bennett decided to be ordained as a Buddhist monk, taking the name Ananda Metteyya. He was one of the earliest Westerners to become a Buddhist monastic. While in Burma, the conviction grew within Bennett that his life’s mission would be to bring Buddhism to Great Britain. He established and was editor of the international English-language magazine Buddhism: An Illustrated Quarterly Review. The first volume appeared in September 1903. Within a year, the journal was being sent free to nearly 600 libraries in England and Europe, with the request that each copy be left on reading room tables until the next issue arrived. Donations from Burmese Buddhists made this possible.

In 1908, Bennett led a mission to England with the goal of presenting and promoting Buddhism as a viable, living religion in the British Isles. To assist him, a handful of supporters established the Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland. During this period he wrote a book, The Religion of Burma, explaining Buddhism to Westerners. While his effort to establish Buddhism in Britain was groundbreaking, it could not be classified as successful. Somewhat discouraged and with his asthma returning more intensely, Bennett returned to Burma for physical and spiritual renewal. However, by 1914 his asthma had become so severe that Burmese doctors urged him to return to England where treatment was thought to be better. Reluctantly he left for England, but even there his asthma continued to worsen. In fact, it became nearly impossible for Bennett to leave his bed, forcing him to become dependent upon others. A physician member of the Liverpool branch of the Buddhist Society invited Bennett to live with him and provided medical care. A Buddhist woman in England provided a small financial sum yearly to assist with expenses, but it wasn’t enough so other supporters wrote an appeal in The Buddhist Review asking for donations to save Bennett from being placed “in some institution supported by public charity.”

Whenever his energies returned, even briefly, Bennett worked to revitalize the Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland, which had been disrupted and decimated by World War I. He also continued writing, speaking, and leading meditation. Bennett resumed editorship of The Buddhist Review and continued editing until his death at the age of 50 on 9 March 1923. Bennett died in complete poverty. A Buddhist funeral service was arranged by a British Buddhist convert and money was cabled by a supporter from Ceylon to buy his grave. It was reported that “flowers and incense were placed on the grave by members of the large gathering assembled, and so there passed from human sight a man whom history may some time honor for bringing to England as a living faith the Message of the All-enlightened One.”

When word of his death reached his Ceylonese colleagues, they eulogized him in a 1923 essay in The Buddhist, a journal published in Colombo: “And now the worker has, for this life, laid aside his burden. One feels more glad than otherwise, for he was tired; his broken body could no longer keep pace with his soaring mind. The work he began, that of introducing Buddhism to the West, he pushed with enthusiastic vigor in pamphlet, journal, and lecture, all masterly, all stimulating thought, all in his own inimitably graceful style. And the results are not disappointing to those who know.”

Buddhist monk. From astrumargenteum.org

Words of wisdom from Allan Bennett

The world can only judge Buddhism by your actions, by your love, your life.

If we [Western practitioners] be indeed worthy of the name of followers of the Buddha, it behooves us, first and foremost, to understand the full meaning that that title has for us; and, not less essentially, to consider what course of action we must follow, if we are to make the most of the great opportunity that our Karma now has brought to us.

All that remains to us is action—not the vain claim that we are followers of the Buddha, whilst yet our lives are empty of the pity and the love and the helpfulness he taught, but action true, following to the best of our small powers.

You will be wondering how the sense of selfhood may be dissolved. The great dissolvent is love. True love is a union of the perceiver with the perceived; and I think you will not deny that the more nearly you come to union with another being, the less emphatically are you yourself.

The Goal of Buddhism is not in the hereafter, but here in the life we live—its goal is a life made glorious by self-conquest and exalted by boundless love and wisdom.

You must understand that Buddhism is no mere cut-and-dried philosophy but a living, breathing truth; a mighty power able to sweep whomsoever casts himself wholeheartedly into its great streams.