Benoy K. Behl was originally interviewed for Buddhistdoor en Español. The following is a translation of that interview.

Benoy K. Behl has been a privileged witness of the beauty, goodness, and compassion that art can bring to the world. Art historian, filmmaker, and photographer, Behl, from New Delhi, is listed in the Limca Book of Records as the most traveled photographer and art historian (Limca is an annual reference book published in India that documenting India’s achievements in various fields) and is the only person to have documented the Buddhist heritage of 19 regions in 17 countries.

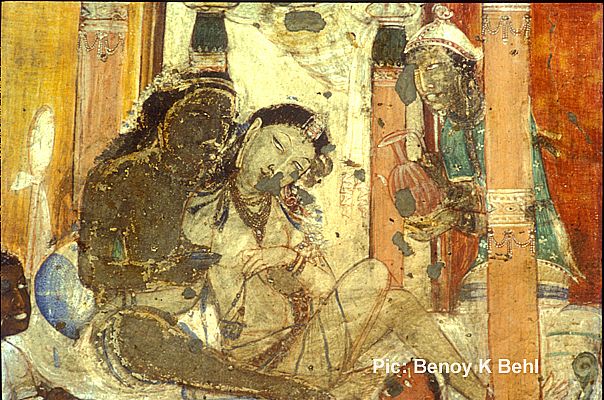

The turning point in his career were his photographs of the ancient paintings in the Ajanta Caves, the earliest surviving paintings of an historic period of the Indian subcontinent. In the horseshoe-shaped gorge of the Waghora River in Maharashtra, western India, 31 caves were excavated in two phases. The first was around the second century BCE and second between the fourth and sixth centuries CE. The paintings and sculptures of Ajanta mainly depict the Jataka tales—stories of the Buddha in his previous lives—and the caves were used for centuries by Buddhist monks as monsoon season retreats.

Behl photographed the Ajanta paintings in their true colors and details in 1991—and a year later he returned to redo and perfect the entire project. After publishing these photographs in National Geographic, museums and universities around the world invited him to lecture and show the paintings. The director general of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) wrote to him, saying: “You have conquered the darkness of the Ajanta Caves.”

Behl is a leading ambassador of ancient Indian art through his books, photography exhibitions, and documentaries. Some of his films, such as Indian Roots of Tibetan Buddhism and Indian Deities Worshipped in Japan, have won awards at international film festivals.

Buddhistdoor en Español: You have mentioned in a lot of articles the impact you had through your photography of the Ajanta murals. After visiting so many places around the world and seeing the finest Buddhist art, what did you find most extraordinary about the Ajanta murals?

Benoy K. Behl: I have had the good fortune to see and document the finest Buddhist art, at sites such as Borobudur in Indonesia, Sukhothai in Thailand, the 12th century paintings of Bagan in Myanmar, the Dungkar Caves in the Tibet Autonomous Region, the museums of cultural history in Bangladesh, and the Sigiriya Caves in Sri Lanka. What is great in all this art is the sublime vision of life, which imparts a deep look inside the painted and sculpted figures. This is all very exquisite art and it transports you—far from the noise and clamor of the material world—to the peace that can be found within.

Image courtesy of Benoy K. Behl

Having seen this wonderful body of Buddhist art around the world, one comes back to its most sublime source. The paintings of Ajanta are the most exquisite and most complete consecration of the spirit of compassion in Buddhism. There is a grace in this art which moves you completely and transforms you—you just have to give it the opportunity by being in front of it for some time. Scholars and pilgrims have always spoken about “the world of Ajanta,” and this is what I have experienced. The thousands of kind and caring figures painted upon the walls of the Ajanta Caves transport you to a world of caring and compassion. These paintings convey a totality in their vision of life, which changes you forever. The compassionate message of Ajanta is contained in an inscription at the site, which says: “The joy of giving filled him so much that it left no space for the feeling of pain.”

BDE: Let’s go back in time. If you could recreate in film the atmosphere, the sounds, and the people working and visiting the caves during the two phases of construction of the Ajanta Cave murals, what would we see?

BKB: The main thing that one would see is a host of dedicated people, fulfilling their duty in life by painting and sculpting. These were guilds of artists, who considered it their dharma, or sacred duty, to create art that would carry on the knowledge and understanding of life that they had received from their ancestors.

BDE: Is the art of the Ajanta murals under threat?

BKB: In the 1920s and 1930s, before Indian independence, Italian conservators were invited to preserve the Ajanta murals. This was a disaster for the conservation of the paintings as these conservators applied shellac (a type of varnish) upon the paintings, which they believed was the best way to preserve them. Over time, the shellac yellowed and darkened very considerably as it collected dust from the atmosphere. For decades, the Archeological Survey of India has been carefully removing the shellac to reveal the colors and details of the paintings. Some of this delicate exercise has been successfully completed, but much more needs to be done.

Besides intrusive human activities like the application of shellac, there are other natural factors that endanger the paintings. There is some seepage of moisture from the roofs of the caves, coming from the distant hilltop above. The ASI is doing everything possible to protect the paintings.

Another damaging factor is the accumulation of humidity and bacteria within the caves, caused by the large number of visitors in recent years. An interpretive center has been created near the caves, with the hope that many of the visitors would be drawn there and would not spend so much time inside the caves themselves.

BDE: India has one of the finest painting traditions in the world, but it seems that many of the artists of those remote times are unknown today. Could you mention some of the highlights covered by the most ancient art treatise, the Chitrasutra of the Vishnudharmottara Purana?

BKB: The inheritance of the tradition of painting that was received by the artists of Ajanta was documented in the Chitrasutra from the fifth century CE. This treatise gives hundreds of details on how to paint. For example, Indian painters concentrated immensely on portraying the feelings of their subjects through their eyes, as the eyes are windows to the soul. So we find five kinds of gazes that are depicted in the Chitrasutra: chapakara or meditative, matsyodara or lovelorn, utpalaptrabha meaning placid or peaceful, padmapatranibha: frightened or weeping, and sankhakriti: angered or deeply pained.

The paintings of Ajanta were made by the inheritors of a very long tradition. They were guilds of painters who painted palaces, temples, and caves. The art of painting was their legacy and it was their duty in life to paint. As you may imagine, they had no need to write their names on the paintings. It was a great sense of importance and fulfilment to play one’s role as a part of the world.

These painters had a great vision of humanity and compassion, which moves us and completely enthralls us to this day.

BDE: At what point did the Buddha start to be represented as a human in the Ajanta artwork and in Indian art in general?

BKB: As the ego and belief in one’s identity is considered to be an illusion of our limited sensibilities, the focus was never on the individual. For about a thousand years, in early times, up until the seventh century CE, a vast quantity of art was produced in India. This art depicted deities, mythical creatures, animals, plants, trees, forms which combined these beings in a great harmony, and also common men and women. Yet this art never depicted any personalities, not even the kings under whose rule the works were created. Nor was the name of the artist mentioned. According to the Chitrasutra, personalities are too unimportant to be depicted in art. The purpose of art is a noble one, to show the eternal, beyond the ephemeral forms of the world.

Works of art were meant to convey the Truth as experienced by the artist. No thinker or artist claimed that it was solely he who had seen the Truth. In fact, the great teachers of the ancient period in India, including Gautama Buddha and Mahavira, each stated that they had only followed in the footsteps of others who went before them. The emphasis was on the loss of the ego and not the perpetuation of it. Art was a prime vehicle of the communication of these ideas.

One of the greatest contributions of this philosophic stream is that there are no barriers placed between the spiritual world and the world of the senses. The art of this tradition is a fulsome sharing of the life experience in all its aspects. It sees our perceptions, from the sensory to the highest realms of the spiritual, as a continuous path. It harnesses our faculties and perceptions to help us understand and reach out to the divine, through all of our emotional and other resources. This philosophy does not seek to deny our response to the splendor of the world around us. In fact, it sees this beauty as a reflection of divine glory. Thus the human form is not presented in a manner which would awaken base desires that burden us. Instead, Indian art recognizes the grace in all human and other forms and seeks to elevate us through our aesthetic response.

Buddhas in human form thus came to be seen in Indian art, along with other deities, from about the first century BCE–first century CE. Therefore, by the time of the second period of Ajanta, these are commonly seen.

BDE: You developed a low-light photography technique to photograph all the murals in Ajanta. How was this experience?

BKB: The Ajanta work was a technical challenge to begin with. This photography in the dark captured the details and colors that had never been known to the world before.

But what happened in the process of my spending long, long hours with these beautiful paintings was something else, which was actually more important than the technical achievement. It was a close and concentrated exposure that I received to this ancient Indian art, in the process of spending so much time in front of the paintings. This was the transforming experience of my life. Out of those glimpses came a clear knowledge that compassion is all that there is. Knowledge is different from something you read in a book. Knowledge is something that you know, which has become part of your consciousness.

Benoy K. Behl’s documentary The Indian Roots of Tibetan Buddhism:

See more