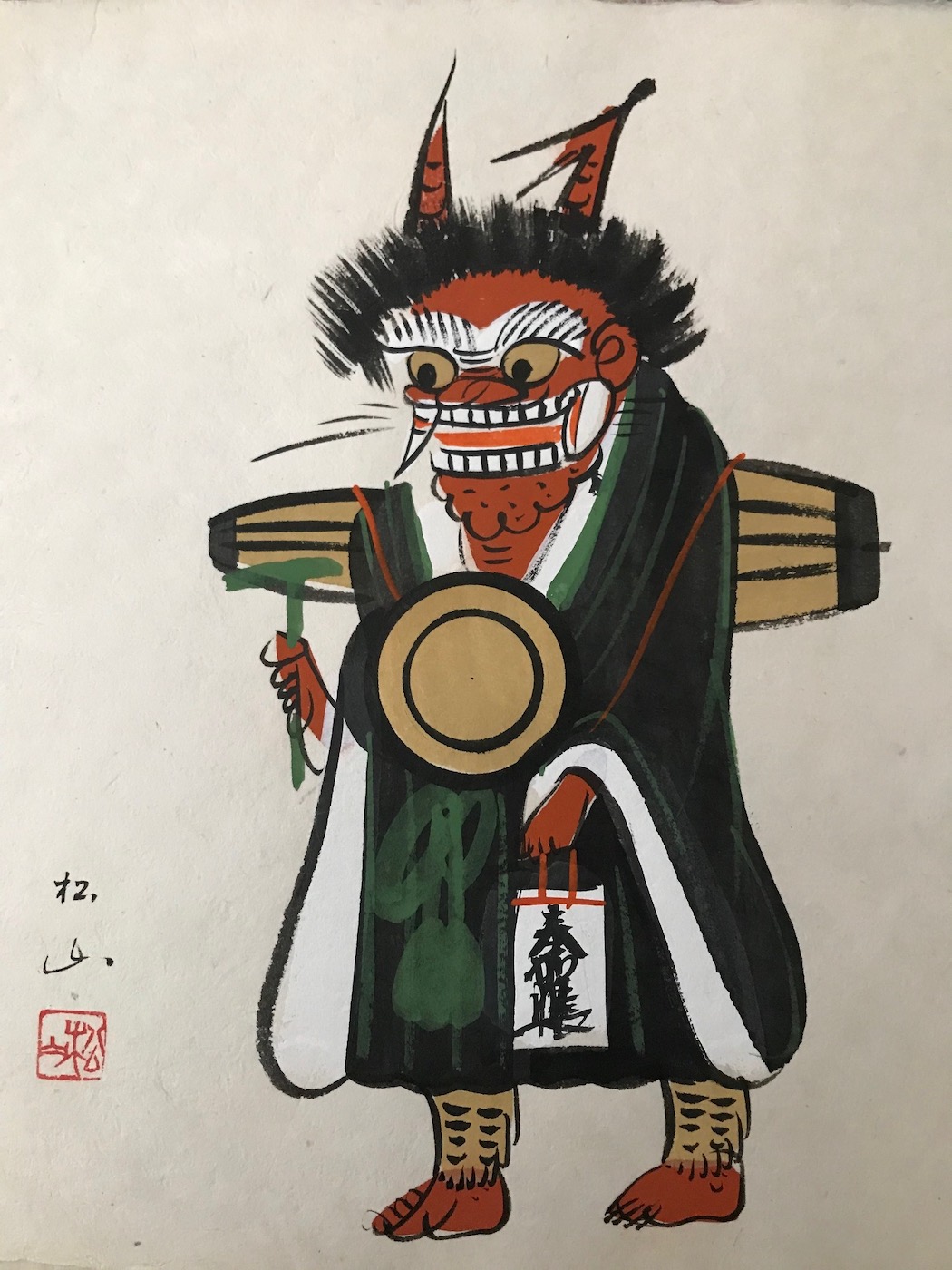

Shozan. Ink and color on paper, late 20th century.

Image courtesy of the author

In the Japanese tradition of Otsu-e—folk paintings from the town of Otsu near Kyoto—one of the most striking and humorous images is that of a hairy demon (Jap: oni), with one crooked horn, huge teeth, and bulging eyes, dressed in the robes of an itinerant Buddhist priest. He carries an umbrella on his back, a gong around his neck, a striker in one hand, and a Buddhist subscription list (Jap: hogacho) in the other. The image is known as Oni no Nembutsu, the Praying Demon, as his mouth is open reciting the nembutsu, a chant believed by Buddhists of certain schools to help them attain salvation in a Buddhist paradise. The amusing image of a demon that has apparently converted to Buddhism can be interpreted in several ways, in part thanks to the inscriptions on 19th century Otsu-e that provided warnings to accompany the images. Some inscriptions warn against the superficial appearance of goodness, even within the Buddhist clergy—not unlike the biblical warning to beware wolves in sheep’s clothing. Others suggest that even the most evil beings, including fierce demons, can be saved by the Buddha’s teachings.

Images of creatures dressed up as or impersonating Buddhist priests, monks, and even the Buddha date back many centuries in Japan. One of the most notable early examples is a set of four scroll paintings known as Choju-jinbutsu-giga (Frolicking Humans and Animals) or Choju-giga (Frolicking Animals) for short. Created by Japanese artist-monks in the 12th and 13th centuries, these paintings depict frogs, rabbits, monkeys, and other animals engaging in human activities, including bathing in a lake, wrestling, taking part in a Buddhist funeral, and praying to a large frog Buddha. In the above segment, a monkey plays the role of a Buddhist priest conducting a ceremony before the frog Buddha. Behind him a rabbit and a fox read and chant sacred texts, while a group of monkey and fox mourners sit in attendance. With their anthropomorphic portrayal of animals, these scrolls have been considered by some scholars to be works of satire, mocking Buddhist priests at a time when they held considerable power over the population. However, the scrolls may have been painted by Buddhist monks, including the artist-monk Toba Sojo (1053–1140), and were been kept as treasures of the Kyoto temple Kozan-ji for centuries (before being housed at the Tokyo National Museum), suggesting that the temple may not have viewed them as critical of the Buddhist teachings.

Bronze, early 20th century. From bonhams.com

Instead, the belief that all creatures can attain enlightenment and should be treated with compassion may explain the affection shown toward creatures who disguise themselves as Buddhist priests in Japanese folklore and art. The fox, or kitsune, typically associated with Inari, the Shinto deity of the harvest, has long been considered a shapeshifter in Japanese folklore, believed to transform into a beautiful woman and even a Buddhist nun. Another shapeshifter is the tanuki, or raccoon dog, who is said to be able to transform into a Buddhist priest. Folk tales abound of tanuki visiting villages and knocking on doors late at night in the guise of priests begging for food or sake.

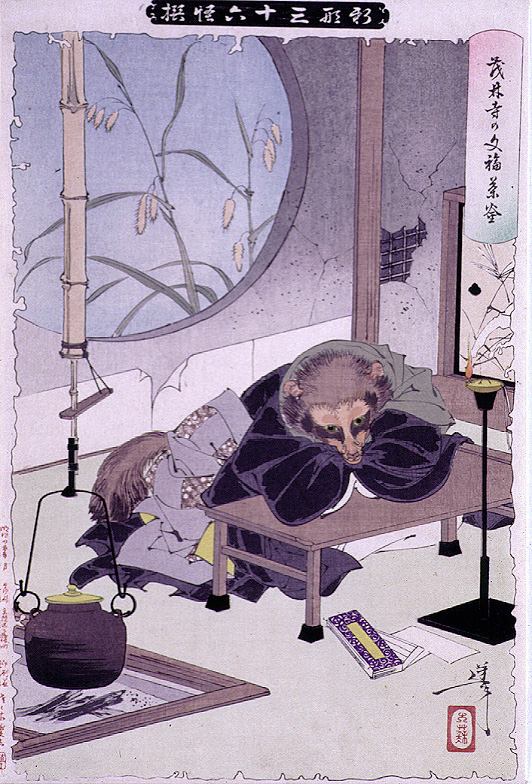

Thirty-six Ghosts. Full-color woodblock print on paper, 1892.

Collection of Scripps College, Claremont, California

In one tale, a tanuki was saved by a woodcutter and, out of gratitude, transformed into an iron kettle. The woodcutter then sold the kettle for a good price to the Buddhist temple Morin-ji. When a priest placed the kettle over a fire to boil water, however, the tanuki screamed in pain, changed back into its true form, and ran around trying to escape. In one ending, the tanuki was caught, changed back into a kettle and was stored away in a box, but in a second version, the creature escaped and found its way back to the woodcutter, for whom it performed as a dancing tea kettle, making a fortune for the man. The tale is illustrated by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–92) in the print The Lucky Tea Kettle of Morin-ji, from his series Thirty-six Ghosts, published in1892. Apparently, while living at the temple as a kettle, the creature sometimes transformed into a priest, although his true form appeared when he napped. In Yoshitoshi’s print, the tanuki is shown wearing a priest’s robes and resting its head on a table, having fallen asleep while reading a Buddhist text, which is shown lying on the floor. Hanging over the brazier beside him is an iron kettle—a reminder of his other form. While many representations of the tanuki are comical, Yoshitoshi portrays the creature who shapeshifted in order to help the another with sweetness and empathy.

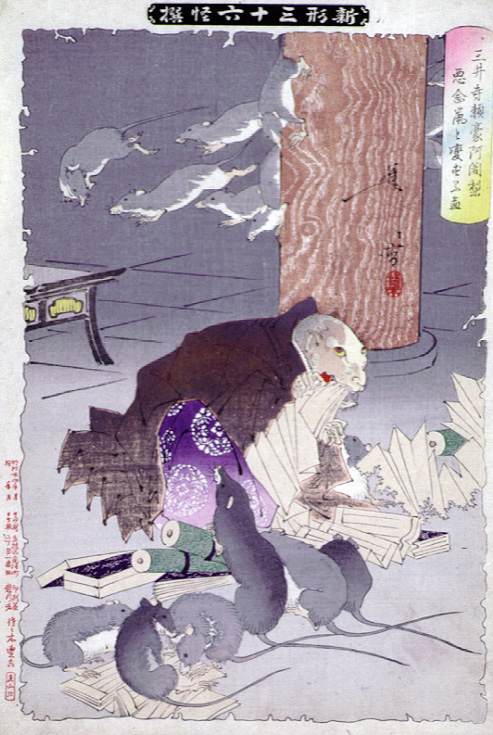

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from the series Thirty-six Ghosts. Full-color woodblock

print on paper, 1891. Collection of Scripps College, Claremont, California

Not so sweet, however, is Yoshitoshi’s depiction of the legendary Raigo, an influential Buddhist priest at Mii Temple in Kumano who served as spiritual adviser to Emperor Shirakawa (r. 1073–87). For many years Shirakawa had no male heir so he sought advice and prayers from Raigo. After several pilgrimages to Mii-dera, a son, Prince Atsuhisa, was at last born. Shirakawa was overjoyed and offered Raigo anything he wanted. Raigo asked nothing for himself, but requested a raised platform for his temple upon which prayers could be offered. The emperor was fearful of the growing power of the Buddhist clergy and refused to grant his request. Infuriated, Raigo shut himself away in his private room and refused to eat. Despite the emperor’s attempts to make amends, Raigo starved himself to death. Prince Atsuhisa died soon afterward. Raigo’s vengeful spirit then changed into a thousand rats, which infested the temple and destroyed the emperor’s sacred books and scrolls. In Yoshitoshi’s print The Priest Raigo of Miidera Transformed by Wicked Thoughts Into a Rat, the animal in the robes of a priest represents an opposite transformation—from priest to beast, as a result of bad karma and negative thoughts. The emperor failed to keep his promise to the priest, and the priest allowed himself be consumed by his own anger.

This abundance of animals and supernatural creatures dressed as Buddhist priests in Japanese folklore and art stands as a testament not only to the imagination and humor of Japan’s storytellers and artists over the centuries, but also the complex relationship between the lay population and the Buddhist clergy, who occupied a prominent role in Japanese society for more than 1,000 years. While Buddhist monks and nuns have largely been respected as upstanding and trustworthy figures in the community, some of the more conspicuously wealthy temples and influential priests, perhaps overly preoccupied with more temporal matters, have not always shared the same level of trust. As a result, much folklore has focused on perceptions and depictions—sometimes caricatures—of these intriguing figures, symbolized by their black, flowing robes and supernaturally karmic transformations from animals into priests and back, and providing fascinating inspiration for artists and delightful, insightful tales and imagery for the rest of us to enjoy and perhaps ponder.