There are many reasons why Japanese Buddhism took hold in North America. While it is common to identify trends at the global level—the end of World War Two, the dialogue between American and Japanese writers and artists during the Beat Generation, and so on—we too often overlook the individuals who drove the diffusion of diverse traditions and the conversation between East and West.

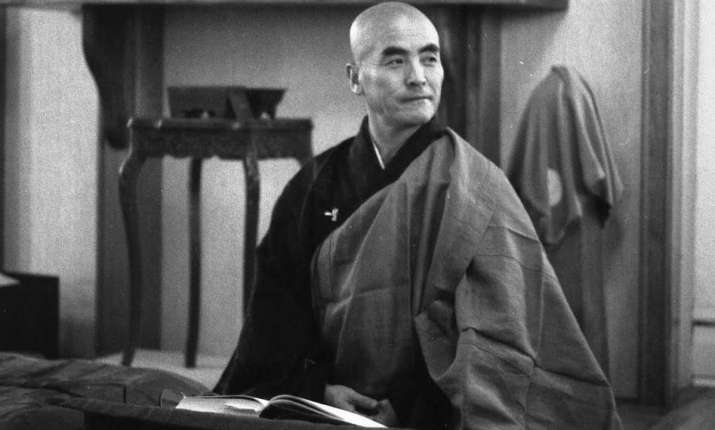

Soto Zen master Dainin Katagiri Roshi (1928–90), who founded the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center in 1972, was one of these people who were uniquely equipped to understand the needs and the culture of the people of America while disseminating Zen teachings with authenticity. He was a prolific writer and his teachings were widely circulated during his life. Last year, a new volume containing his most persuasive thoughts about the nature of existence, the meaning of human activity, and our personal purpose in life—whatever our background or context—was published, titled The Light that Shines Through Infinity: Zen and the Energy of Life.

The book is divided into five parts, each with their own sub-chapters, devoted to big topics: life force and life, practice and enlightenment, body and mind, wisdom and compassion, and peace and harmony. There are too many inspiring passages to quote in one short review, but what this book aims to do is to hold up, in true Zen tradition, a mirror to one’s deepest, most intimate self. Edited by Andrea Martin, a student of the late teacher, this book provides cogent counsel on how “to be with Dharma,” to live “wholeheartedly, constantly trying to be with that stream of great energy.”

Katagiri Roshi equates this “stream of great energy,” a constant theme in this book, with reality or life itself. It is also inseparable from the notion of Dharma, which in his view should not be divided into the two classical definitions of “the principle of how the life of all sentient beings is constructed,” (the Dharma that every Buddha in each world-age discovers and teaches) and “everything in the phenomenal world” (dharmas in Abhidharma philosophy).

He disagrees with this bifurcation of the Dharma by noting: “The phenomenal world is not something separate from the ultimate nature of existence; the phenomenal world includes the ultimate nature of existence. . . . Buddha’s teaching is also called dharma. But Buddha’s dharma is not something different from human life; life itself is Buddha’s teaching. Whether you are conscious of it or not, you are living right in the middle of dharma.”

When we are trying to align ourselves with reality, we are really trying to align our life force with the flowing energies of the cosmos, embracing it joyfully and therefore living authentically and being who we were meant to be. “Real reality is just activity, function, or movement—the universal energy is the point that Buddhism is always interested in.”

The vast majority of the book is focused on assisting the reader to be truly alive, that is, in tune with reality’s cosmic energy. For example: “Even if you don’t understand Zen teaching intellectually, still you can pay kind, compassionate attention to the things around you. Pay attention to others, not just yourself. This is the practice of egolessness. It is a practical way to live every day. Sooner or later you will taste the lively energy of life.”

Apart from practicing compassion, awareness of life’s energies is also attained through breathing in concentrated meditation. “All aspects of daily living are great opportunities through which you can experience samadhi, because every moment is a place where you can become one with an event. Instead of always using the energy of your life to create subject and object, sometimes use it to unify your body and mind in samadhi. Then your self-centered consciousness completely drops off, and you can see the immensity of your life.”

I feel this kind of language echoes of Chinese chi or Japanese ki. Even though it does not sound like “orthodox” Buddhism, Katagiri Roshi explains its significance for Buddhist doctrine in parts three and four, along with exploring some implications for our relationships and participation in larger society in the fifth part. This is tied up with the Mahayana idea of repentance. Rather than being restitution for sin or guilt, repentance in the Mahayana tradition simply means realignment of our delusions with “thusness” (tathata in Sanskrit): that which is. “Repentance is a way to accept your ordinary life and then use that life to go beyond it. . . . So repentance in thusness means that your body and mind stand up straight in the whole universe.”

In the Mahayana conception of the spiritual path, humanity undergoes evolution towards bodhisattvahood and finally Buddhahood. Yet the Buddha knows our life direction far better than we do. “The more you try to move toward a great image of human life, the more you find it difficult to keep your life straight. The closer you come to the bodhisattva way of life, the more you encounter obstacles and difficulties created inwardly or outwardly by your life, by others’ lives, and by circumstances. You see how egoistic human beings are, how we hurt ourselves and others. . . . But then, from that pain, appears a sense of prayer or vow: I am weak, but I will try again to proceed in the bodhisattva direction.” I found this distinction between human aims and bodhisattva aims particularly poignant and important.

One of Katagiri Roshi’s greatest strengths was to communicate profound, primeval truths in the everyday language of simply being, living, and doing. His pedagogical effortlessness so characteristic of Zen is evident throughout this book, and manifests as a life-affirming call to surrender to the joy of life and the path of Dharma.

References

Katagiri, Dainin. 2017. The Light that Shines Through Infinity: Zen and the Energy of Life. Boulder, Colorado: Shambhala.