Matthieu Ricard explored the trajectory of one of the greatest Tibetan Buddhist masters of the 19th century, Patrul Rinpoche, for nearly 40 years. The result of his research is a remarkable book, a time capsule that allows us to delve into the life of this teacher, who is a landmark in the history of Tibetan Buddhism.

All of those who came into contact with Patrul Rinpoche were deeply impressed by the peerless glow of his wisdom, by his compassion, and by his lifestyle as a wandering yogi, free from attachment and aversion. His best-known work, composed in a cave above a Dzogchen monastery, is The Words of my Perfect Teacher, a book revered by all four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. As the great master Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche observed, in his time Patrul Rinpoche was unsurpassed in his realization of the Dzogchen view, meditation, and conduct.

Matthieu Ricard’s life follows a remarkable trajectory as well. As a young man, he was conferred a PhD in molecular biology, which he did not follow through professionally because he moved to the Indian Himalaya to live as a Buddhist monk, entirely dedicated to the study and practice of Buddhism. Ricard has been the French interpreter for the Dalai Lama since 1989, has written many books, is a fine photographer, a member of the Mind and Life Institute, and is fully involved in his own humanitarian organization Karuna Shechen.

His book, Enlightened Vagabond – The Life and Teachings of Patrul Rinpoche, was published in English by Shambhala Publications in 2017 and will be published in Spanish by Padmapani Editorial by February 2021.

Buddhistdoor en Español: The process of writing the book was a long and extraordinary journey, compiling stories of Patrul Rinpoche from so many great Tibetan Buddhist masters. Can you share with us some of your memories about this project?

Matthieu Ricard: Well, there were several aspects to it: knowing the extraordinary life story and teachings of Patrul Rinpoche intimately, hearing them from the most inspiring teachers, and visiting the amazing places where he lived and practiced.

In and of itself, the life story of Patrul Rinpoche is a magnificent example of what a perfect Dharma practitioner can be: free from the slightest interest in worldly preoccupations such as wealth and power, material possessions, praise and blame, and filled with limitless compassion for all beings guided by wisdom.

Next, it was so inspiring to hear those stories and teachings from no less than 18 accomplished masters, a number of whom had met direct disciples of Patrul Rinpoche. They would tell the stories in such lively ways that it sometimes felt that it had just happened the day before.

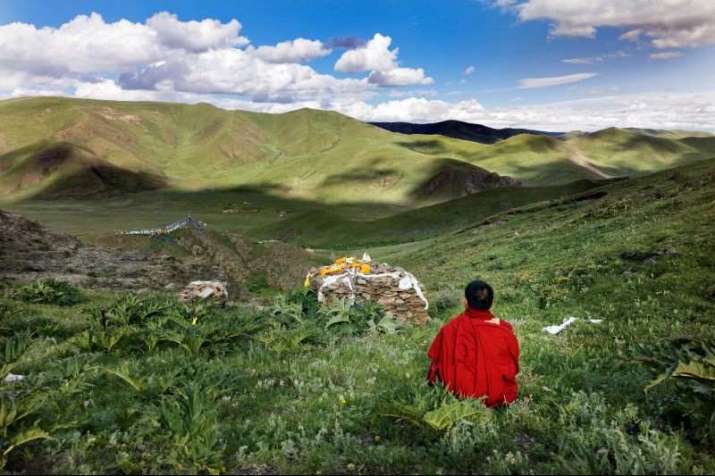

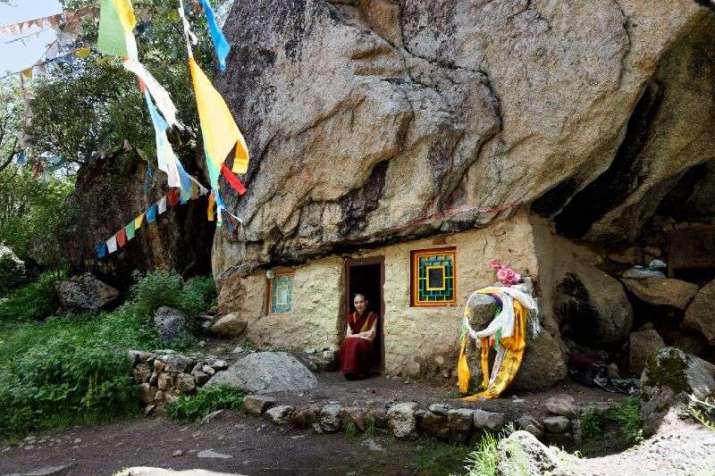

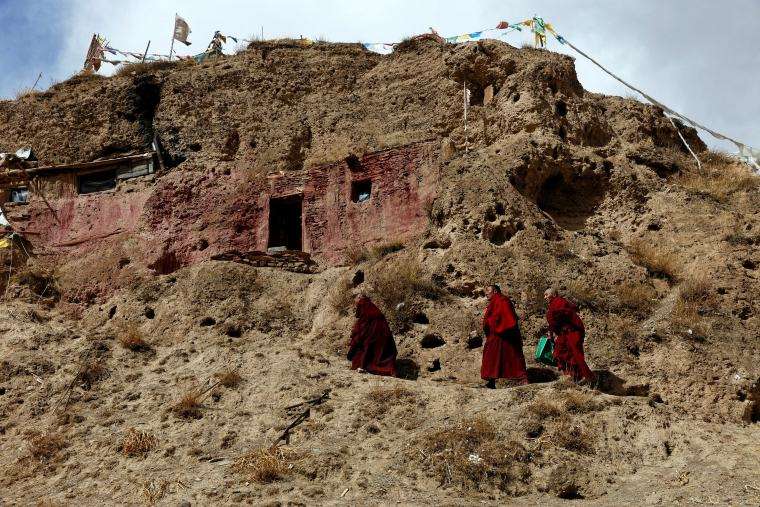

Finally, to visit some of the remote places where Patrul Rinpoche practiced, caves high up in the mountain wilderness above the Dzogchen monastery, a cave overlooking the beautiful Drichu (Yangtse) River valley in Denkhok, and the harsh highlands of Dzagyal Drama Lung, for instance, has been a strong reminder of the need to devote oneself to spiritual practice.

Doing it in a leisurely manner over 40 years also allowed me to gather more stories and visit more places, as I encountered teachers and people who knew about Patrul Rinpoche’s life. I also met some of the descendants of his sister. Time has surely helped to enrich this biography.

BDE: Many teachers recommend that practitioners read the stories of the life and liberation of great spiritual teachers as an inspiration and a model to follow. What would you highlight about Patrul Rinpoche’s life and teachings that Dharma practitioners could treasure?

MR: I cannot say it better than Jigme Khyentse Rinpoche in his foreword:

Even though he is not alive, he is still able to make us feel uncomfortable and to cut through the hypocrisy or insecurities that we have as students. This can transform our lives. Even if we try to ignore this uncomfortableness, his compassionate activity continues to haunt us in spite of our thick-skinned ignorance. I also feel that his biography is invaluable for those who are studying Patrul Rinpoche’s writings such as The Words of My Perfect Teacher. It will give us a greater understanding of what he is transmitting. Not every biography embodies the true meaning of ‘biography’ in Tibetan, which is namthar, or complete liberation, but I feel that this biography does, in the sense that, as we read it, it can liberate us from our confusion.

BDE: Patrul Rinpoche spent most of his life as a wandering yogi, roaming the mountains, living in caves and forests . . . and, as it is said in the book, he very often shared the same advice: “Have a good heart and act with kindness. There is no higher teaching.” This also seems to be the connecting thread in many of your teachings and your books, as in Altruism: The Power of Compassion to Change Yourself and the World. How can we cultivate our hearts and minds so that they remain open and loving even when life gets tough? Why do you think altruism is such a key factor for a happy life and a truly healthy society?

MR: It is precisely when life gets tough that it is best to cooperate, to express solidarity, to be altruistic, and to cultivate boundless compassion. Once I requested His Holiness the Dalai Lama for some advice before going into retreat, and he told me: “In the beginning meditate on compassion, in the middle meditate on compassion, and in the end meditate on compassion.” It cannot be clearer than that.

The pursuit of selfish happiness is bound to fail. It makes everyone miserable and it fails to take into account the fact that all beings are intimately interdependent. Conversely, altruistic love is the best way to accomplish the good of both others and oneself. In this current era, one of our main challenges consists of reconciling the demands of the economy, the search for happiness, and respect for the environment. These imperatives correspond to three time scales: short, middle, and long term.

Altruism is the only unifying concept that provides us a common framework to work together for a better world. If we have more consideration for others, we will move toward a caring economy, we will be more concerned with the improvement of well-being within society, and we will care more about the fate of future generations and the eight million other species who are our co-citizens in this world.

Altruism thus seems to be a determining factor of the quality of our existence, now and to come, and should not be relegated to the realm of noble utopian thinking. We must have the perspicacity to acknowledge this and the audacity to say it.

BDE: You have been an active member of The Mind and Life Institute, an organization that brings together science and contemplative wisdom toward a better understanding of the mind as well as helping to create a positive change in the world. How do you value what has been achieved?

MR: Research in the neurosciences has shown that any form of training induces a restructuring in the brain, both functional and structural. This is also what happens when one trains in developing altruistic love, compassion, and attentive presence.

I joined the Mind and Life Institute in 2000, during an exceptional meeting on “destructive emotions” that took place in Dharamsala, India. Some of the most eminent specialists on emotions, psychologists, neuroscientists, and philosophers gathered to discuss with the Dalai Lama in the privacy of his residence. I had been a long-time friend of Francisco Varela, who created the Mind and Life Institute with Adam Engle in order to organize meetings between the Dalai Lama and great scientists.

One morning, the Dalai Lama said: “All these discussions are very interesting, but what can we really bring to society?” At lunchtime, the participants held a lively discussion and conceived the idea of launching a research program on the short- and long-term effects of training the mind, which is usually called “meditation.” In the afternoon, in the presence of the Dalai Lama, this project was enthusiastically adopted and marked the advent of a new field of research, that of “contemplative neuroscience.”

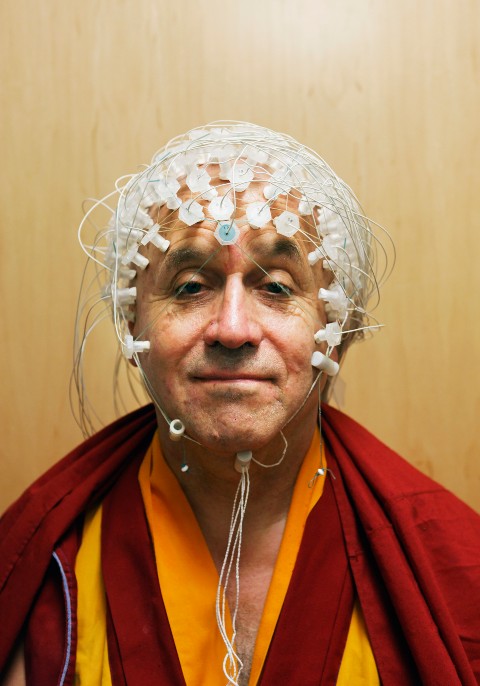

Because of my life journey—the fact that I began a career as a researcher and then devoted myself to the spiritual life—I volunteered to participate in this research. I had not foreseen that I would spend more than 100 hours in MRI scans and be the guinea pig for all kinds of experiments—sudden explosions to study the startle response, transcranial magnetic stimulation to study brain connectivity, water at 49 degrees C, and electrical discharges on the wrists to study the effects of meditation on pain, injection of radioactive substances to measure the metabolism of my aging brain, and more. On one occasion, I spent 10 hours in an MRI in two days. As Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, who also participated in this research, said, the MRI has four characteristics: “It’s narrow, dark, cold, and noisy.”

Wisconsin-Madison in which his brain was investigated by

neuroscientist Richard Davidson. Image courtesy of Matthieu Ricard

I immediately appreciated the warm atmosphere of creativity, discovery, and intellectual rigor that I found among my scientific friends, who became for me a kind of scientific sangha, a virtuous community seeking to do good science and contribute to the welfare of society, as the Dalai Lama had enjoined us to do.

Research has shown, for instance, that when experienced practitioners begin to meditate on compassion, there is a remarkable increase in rapid oscillations in the so-called gamma frequencies and the coherence of their brain activity. This activity, significantly higher than in the control group of people trained for a week in meditation, is “of a magnitude that has never been described in the neuroscience literature,” said Richard Davidson.

The initial results represent the first serious experimental study of meditative states. Published in the prestigious Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the article was downloaded more than 150,000 times. In the words of Richard Davidson: “This work seems to demonstrate that the brain can be trained and physically modified in ways that few people would have imagined.”

Among the various research projects in which I participated, one of the ones that gave very interesting new perspectives on mental states was the one conducted with Tania Singer, which allowed me to distinguish unambiguously between empathy and compassion. This project is also one of those that can have the most valuable practical applications for the many people who are confronted with the suffering of others: caregivers, social workers, and those who care for a suffering loved one. In essence, we have shown for the first time that fatigue or empathic distress leads to emotional exhaustion and burn-out, while altruistic love and compassion, on the contrary, regenerate our ability to deal with the suffering of others with serenity, kindness, and courage. There is no “compassion fatigue,” a term often used in medicine, but there is “empathy fatigue.”

Today, the Mind and Life Institute as well as Mind and Life Europe are widely recognized and respected for their scientific rigor and for the quality of the collaboration with contemplatives in the new field of “contemplative neurosciences” and of clinical research regarding the beneficial effect of mind training on physical and mental health.

BDE: In your writings, you envision a new, fairer global economy and a different way to live our lives that is more responsible with our planet. Do you think the current world crisis could make these changes possible?

MR: Ideally, it should! But, of course, societal change takes time. Fortunately, cultures change faster than genes, but it still takes a generation or two to bring about a deep change of attitude. The respect for human values embodied in altruism is the best way to achieve what I would call a sustainable harmony. The term “sustainable development” is a bit ambiguous, since it evokes quantitative growth, which is clearly no more sustainable simply for the simple reason that infinite quantitative growth requires an ever-greater use of a finite ecosystem. We do not have three or five planets.

The middle way between growth and decline can be found in sustainable harmony, a situation that guarantees everyone a decent way of life and reduces inequality at the same time as ceasing to exploit the planet at such a drastic speed. To bring about and maintain this harmony, we must, on the one hand, lift a billion people out of poverty as soon as possible, and on the other, reduce the rampant consumption taking place in rich countries. We must also gain awareness of the fact that unbridled material growth is not remotely necessary for our well-being.

What good is an extremely rich and all-powerful nation full of unhappy people? By choosing to carry on encouraging growth as though it were “business as usual,” mainstream economists are loading the odds against future generations.

We cannot expect quality of life to be a mere by-product of economic growth, since the two things are not based on the same criteria. It would be more appropriate to introduce the concept of “gross national happiness,” an idea conceived in the little Himalayan country Bhutan. For three decades, they have used a scientific tool to measure various aspects of life satisfaction and its correlation with other extrinsic factors: financial resources, social standing, education, levels of freedom, violence in society, and the political situation, alongside intrinsic factors: subjective well-being, optimism or pessimism, and degrees of egocentrism or altruism.

This seems to be taking us quite far from Patrul Rinpoche’s simple life of wisdom, compassion, and renunciation, but in fact these ideas are inspired by the same principles of discernment and concern for others, here applied to an ever-changing world.

Mireia Pretus studied at the Ramón Llull University in Barcelona, obtaining a degree in journalism. Later, she took a course at the Escola Superior d´Imatge i Disseny (IDEP) about film production and screenplay. In 2001, her interest in Buddhism began and since then she has studied and practiced with various Buddhist teachers, especially in the Tibetan tradition. During these years she has worked intensely as a translator, especially doing simultaneous translation from English to Spanish for several Buddhist teachers, and she has collaborated with Fundación Casa Tibet in Barcelona, the University of Mysticism of Avila, and The Meridian Trust Foundation. She has been a member of the team of the Coordinadora Catalana de Entidades Budistas (CCEB). She currently works at the British NGO The Friendly Hand coordinating educational and health projects in the UK, Spain, India, Peru, and Sri Lanka.

See more

Mind & Life Institute

Interview with Matthieu Ricard (University of Minnesota)

Books by Matthieu Ricard (Matthieu Ricard)

Matthieu Ricard: The Habits of Happiness (YouTube)

Matthieu Ricard: World’s Happiest Man on What Really Matters. (YouTube)